Astronomers define the reflectivity of an object in space using a term called albedo. This is the amount of electromagnetic radiation that reflects away, compared to the amount that gets absorbed. A perfectly reflective surface would get an albedo score of 1, while a completely dark object would have an albedo of 0. Of course, it’s not that black and white in nature, and all objects have an albedo score that ranges between 0 and 1.

Here on Earth, the albedo effect has a significant impact on our climate. The lower the albedo, the more radiation from the Sun that gets absorbed by the planet, and temperatures will rise. If the albedo is higher, and the Earth is more reflective, more of the radiation is returned to space, and the planet cools.

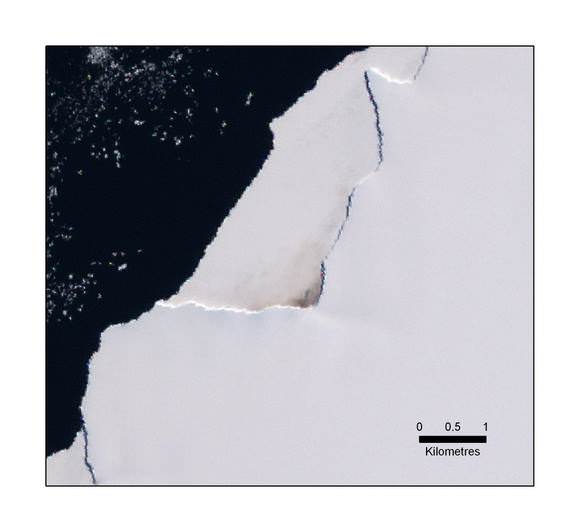

An example of this albedo effect is the snow temperature feedback. When you have a snow covered area, it reflects a lot of radiation. This is why you can get terrible sunburns when you’re skiing. But then when the snow covered area warms and melts, the albedo goes down. More sunlight is absorbed in the area and the temperatures increase. Climate scientists are concerned that global warming will cause the polar ice caps to melt. With these melting caps, dark ocean water will absorb more sunlight, and contribute even more to global warming.

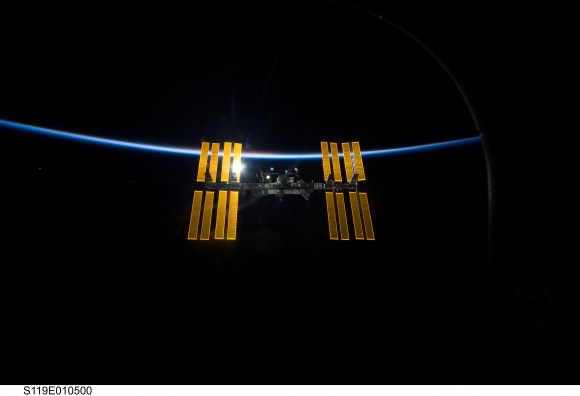

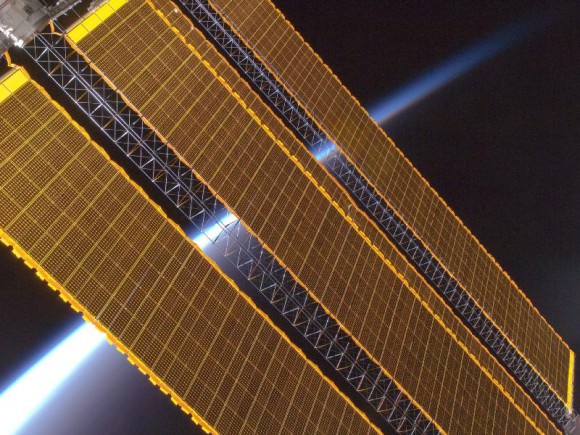

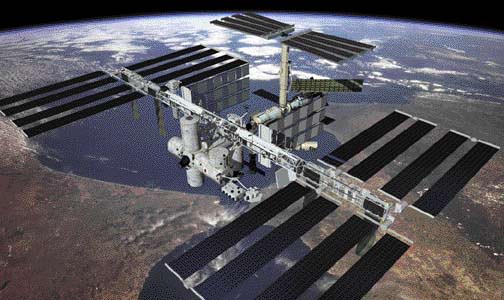

Earth observation satellites are constantly measuring the Earth’s albedo using a suite of sensors, and the reflectivity of the planet can actually be measured through Earthshine – light from the Earth that reflects off the Moon.

Different parts of the Earth contribute to our planet’s overall albedo in different amounts. Trees are dark and have a low albedo, so removing trees might actually increase the albedo of an area; especially regions typically covered in snow during the winter.

Clouds can reflect sunlight, but they can also trap heat warming up the planet. At any time, about half the Earth is covered by clouds so their effect is significant.

Needless to say, the albedo effect is one of the most complicated factors in climate science, and scientists are working hard to develop better models to estimate its impact in the future.

We have written many articles about the albedo effect for Universe Today. Here’s an article discussing the albedo of the Earth, and how decreasing Earthshine could be tied to global warming.

There are some great resources out on the Internet as well. Check out this article from Scientific American Frontiers, and some cool photos of different colors of ice.

We have recorded a whole episode of Astronomy Cast just about the Earth. Listen to it here, Episode 51: Earth.

Reference:

Encyclopedia of Earth