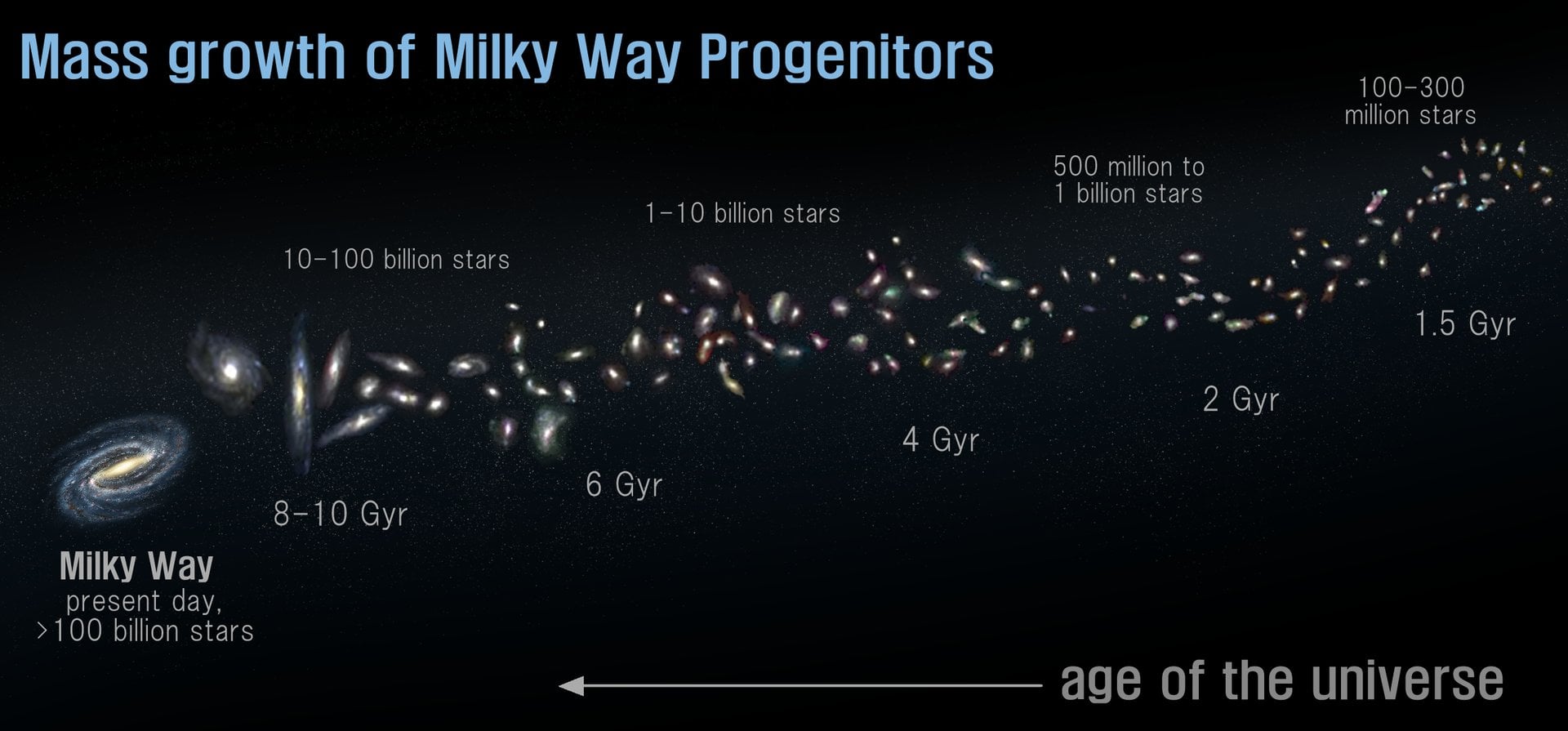

The Milky Way has a long and fascinating history that extends back to the early Universe - ca. 13.61 billion years ago. In that time, it has evolved considerably and merged with other galaxies to become the galaxy we see today. In a recent study, a team of Canadian astronomers has created the most detailed reconstruction of how the Milky Way evolved from its earliest phases to its current phase. Using data provided by the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), the team examined 877 galaxies whose masses and properties closely match what astronomers expect the Milky Way looked like over time ("Milky Way twins").

The galaxies in this survey spanned a huge range of cosmic time, from when the Universe was 1.5 to 10 billion years old (12.3 to 3.5 billion years ago). By observing more distant galaxies that existed when the Universe was younger, the team created a visual timeline of the Milky Way's evolution. To their surprise, they found that the Milky Way had a remarkably turbulent youth before settling into the stable and structured "adult" spiral we are familiar with today.

The study was led by Dr. Vivian Tan, who recently completed her Ph.D. at York University under the supervision of Prof. Adam Muzzin. They were joined by researchers from the Dunlap Institute for Astronomy & Astrophysics, the SMU Institute for Computational Astrophysics, the Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, the Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory, the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI), the Herzberg Astronomy & Astrophysics Research Centre, and multiple universities. The paper that describes their findings appeared in The Astrophysical Journal.

*Gemini South image of NGC 5426-27 (Arp 271) as imaged by the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrograph. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA*

*Gemini South image of NGC 5426-27 (Arp 271) as imaged by the Gemini Multi-Object Spectrograph. Credit: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA*

In accordance with the Hubble Sequence, astronomers classify galaxies into three groups based on their shapes: elliptical, spiral, and barred spiral. Elliptical galaxies are the product of mergers, are populated by old (redder) stars, and have little structure or interstellar dust and gas. Lenticulars are a transitional type of galaxy, combining the features of spirals and ellipticals like a bright central bulge surrounded by an extended disk. Spirals, noted for their pinwheel shape, consist of a central bulge and a flattened disk with stars forming a spiral structure. Those that fall outside of these three morphologies are known as "Irregular galaxies."

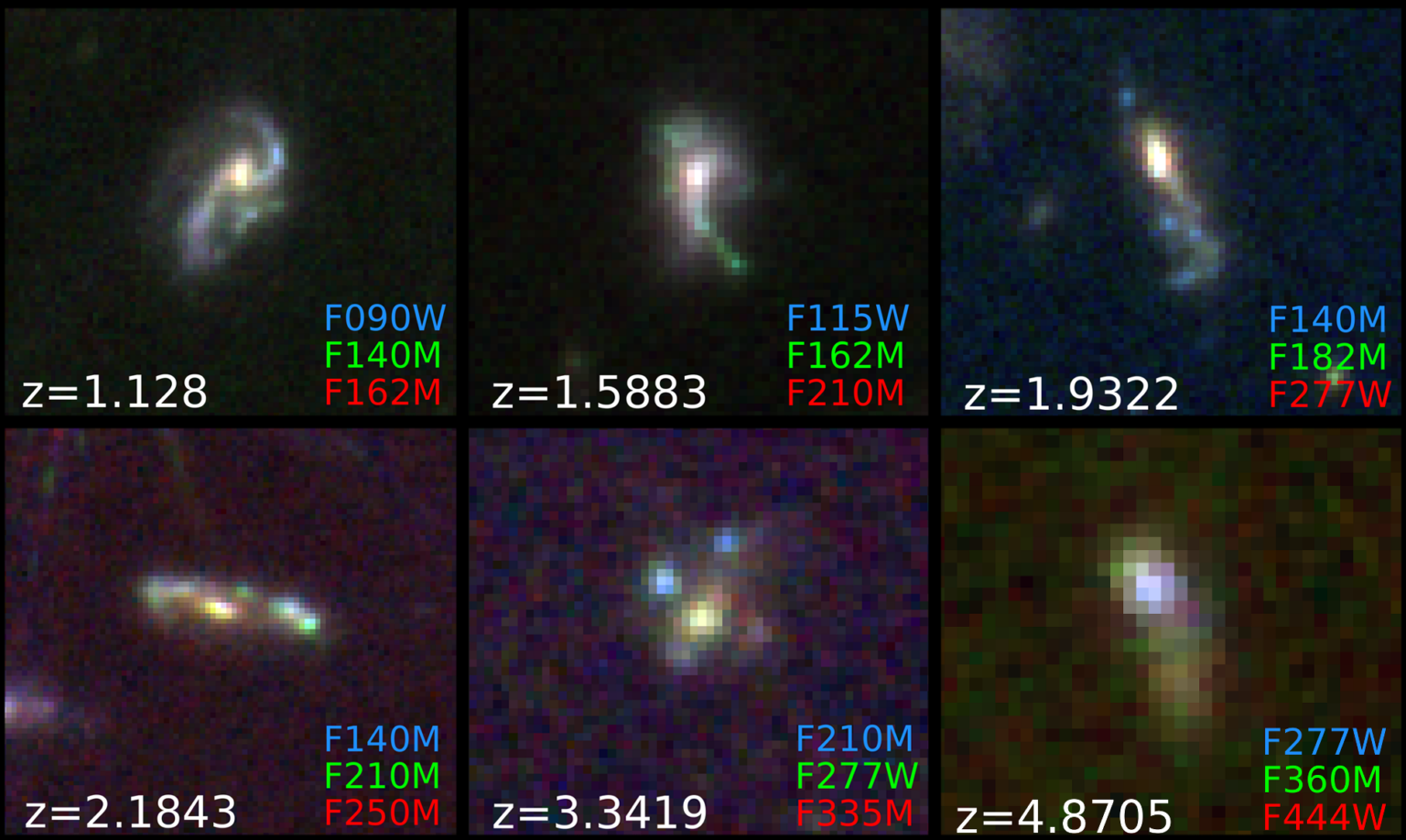

Based on Hubble's Deep Fields program and other observations of the early Universe, astronomers have noted that early galaxies began as small, blue, irregular galaxies. Over time, they evolved to become star-forming spirals, eventually giving rise to red-sequence non-star-forming ellipticals. The galaxies in the sample are dated to a crucial epoch when galaxies went from being smaller, elliptical masses of stars to stable disk galaxies that are common today. For their study, the team combined high-resolution imaging from the JWST and the venerable Hubble to create a census of 877 early galaxies.

The JWST observations were obtained as part of the Canadian NIRISS Unbiased Cluster Survey (CANUCS). This Canadian observing program uses data from Webb's Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS). This instrument was built by the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) in partnership with the Université de Montréal, the National Research Council Herzberg Centre for Astronomy and Astrophysics, and Honeywell Robotics. CANUCS uses data from the NIRISS instrument to observe five galaxy clusters, which are natural gravitational lenses that allow astronomers to observe fainter, more distant galaxies.

Combined with visible-light observations by Hubble, the team created resolved stellar-mass and star-formation-rate (SFR) maps for each galaxy observed. These maps showed where existing stars were located and where new stars were forming during different phases of the galaxies' evolution. The results indicated a clear pattern across the entire sample, showing that Milky Way galaxy twins grew from the inside out between 3 and 4 billion years after the Big Bang. They begin with dense central regions and accumulate mass in their outer regions through mergers and new star formation, gradually forming extended spiral structures.

Tan and her colleagues then ran state-of-the-art computer simulations that track the evolution of Milky Way–like galaxies, which largely confirmed the inside-out growth model they observed. However, the simulations failed to reproduce the highly central nature of early galaxies in some cases and failed to predict how rapidly mass accumulates in the outer regions. These results provide valuable constrains for theoretical models of galactic evolution and the mechanisms involved, including feedback, merger rates, and disk formation.

Mosaic of some of the Milky Way progenitors. Credit: Vivian Tan et al. (2025)

Mosaic of some of the Milky Way progenitors. Credit: Vivian Tan et al. (2025)

“Astronomers have been modeling the formation of the Milky Way and other spiral galaxies for decades,” said Tan. “It's amazing that with the JWST, we can test their models and map out how Milky Way progenitors grow with the Universe itself." A major takeaway from this study is the indication that the Milky Way's early history was more chaotic than previously expected. From their observations, it appears that galaxies in this early period were constantly colliding and accreting material, triggering intense bursts of star formation.

This is evidenced by the highly disturbed shapes and asymmetric features they observed. In contrast, Milky Way twins appear much more stable in later cosmological periods, characterized by smoother structures and more evenly distributed star formation. Said Adam Muzzin, an astrophysics at York University and a co-author of the study:

This study is a significant step forward in understanding the earliest stages of the formation of our Galaxy. However, this is not the deepest we have pushed the telescope yet. In the coming years, with the combination of JWST and gravitational lensing we can move from observing Milky Way twins at 10 percent their current age to when they are a mere 3 percent of their current age, truly the embryonic stages of their formation

This study is a significant milestone for the CANUCS collaboration and other Canadian astronomers engaged in JWST research. In the meantime, the CANUCS team is working to expand this study and build a more complete picture of how galaxies like the Milky Way have evolved. This will involve combining additional exceptionally high-resolution data with updated simulations to analyze even larger samples of Milky Way twins. In so doing, they hope to precisely determine when galaxies like the Milky Way settled into stable disks, how long the process took, and what physical processes drove the transition.

Further Reading: York University, The Astrophysical Journal

Universe Today

Universe Today