What are other solar system's like? How is our similar to others, and how is it different? In this age of exoplanet discovery, we've found more than 6,000 confirmed exoplanets, and while some of the planets in our system are similar to exoplanets, the exoplanet population contains planet types that aren't reflected in our system.

But there's more to a solar system than a star and planets. There are other significant features like asteroid belts, and in our system, the Kuiper Belt. The Kuiper Belt is a circumstellar disk that's home to bodies left over from the Solar System's planet formation period. Pluto is often regarded as the inner boundary of the belt, and the belt contains both rocky bodies and bodies composed of frozen volatiles. Closer to the Sun, the asteroid belt is full of remnants from the Solar System's early days.

These bodies are remnants from the planet formation process. Astronomers are particularly interested in objects between about 1 km and several hundred km in diameter. They're evidence of the planetary formation process, planetesimals that got stuck at that size and didn't become part of planets.

Astronomers are interested in understanding this population of objects in our Solar System and in others, because they open a window into the planet formation process, and how it might be similar and/or different in different systems. But imaging them is extremely difficult.

New research used the SPHERE (Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch) instrument on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope to study debris disks in other solar systems. The results are in a paper published in Astronomy and Astrophysics titled "Characterization of debris disks observed with SPHERE." The lead author is Natalia Engler from ETH Zurich (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich).

SPHERE is an exoplanet-finding telescope with adaptive optics and a coronagraph. It can provide direct images of exoplanets in some cases, something that is extremely difficult to do. Even though our best direct exoplanet images aren't much more than indistinct blobs, they're still valuable.

The debris disks in these exo-systems are next to impossible to image directly. But SPHERE was still able to help. Engler and her co-researchers used SPHERE to create a gallery of these disks by using another of its properties: it uses polarimetry to filter out light from dust particles.

"This data set is an astronomical treasure. It provides exceptional insights into the properties of debris disks, and allows for deductions of smaller bodies like asteroids and comets in these systems, which are impossible to observe directly,” said co-author Gaël Chauvin from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, who is also a project scientist for SPHERE.

Imaging any of the 1 km to 100 km diameter bodies in the disks is impossible, but SPHERE can image the collective dust that exists in the rings with these bodies. That can provide critical information about the nature of the disks.

Young solar systems are choked with dust. The frequent and numerous collisions between planetesimals that defines the planet formation stage creates copious amounts of it. Over time, the star or stars in systems dissipate the dust with their radiation pressure. Eventually, solar systems reach a state like ours, where left-over smaller bodies are confined to distinct rings, like the main asteroid belt and the Kuiper Belt in our Solar System. Some dust is also present and is called zodiacal dust.

But for about the first 50 million years of a solar system's life, it's choked with dust. That dust reflects a lot of light, although the blinding light of the star drowns it out. But SPHERE can use it coronagraph, adaptive optics, and polarimetric capabilities to see it.

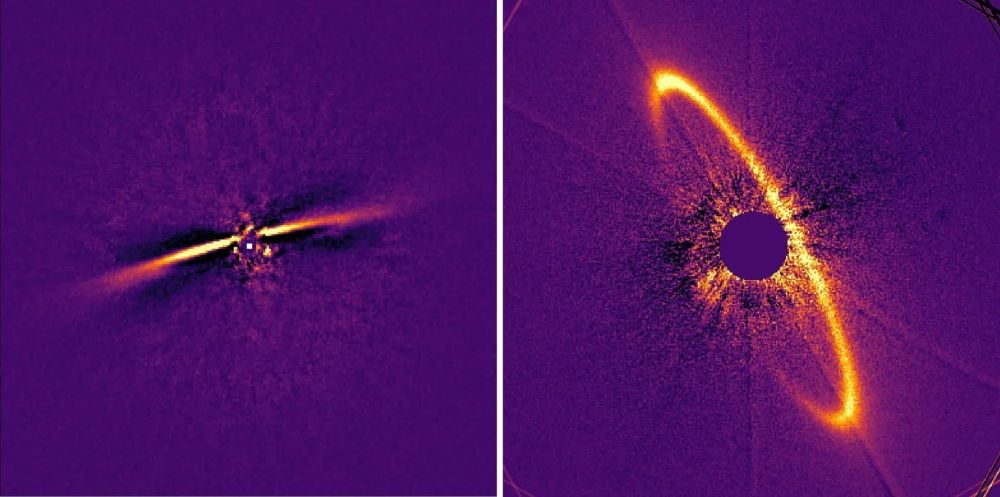

*These images show the debris disks around the star HD 106906 (left), a binary star system about 340 light-years away, and around HR 4796 (right), another binary star system about 235 light-years away. They highlight the amount of detail that is possible with SPHERE. Image Credit: © N. Engler et al./SPHERE Consortium/ESO*

*These images show the debris disks around the star HD 106906 (left), a binary star system about 340 light-years away, and around HR 4796 (right), another binary star system about 235 light-years away. They highlight the amount of detail that is possible with SPHERE. Image Credit: © N. Engler et al./SPHERE Consortium/ESO*

"This study aims to characterize debris disk targets observed with SPHERE across multiple programs, with the goal of identifying systematic trends in disk morphology, dust mass, and grain properties as a function of stellar parameters," the authors write in their research. By using imaging and modelling, the researchers are improving their understanding of the circumstellar material in these disks, and are working to place these disks in the larger context of solar system architectures.

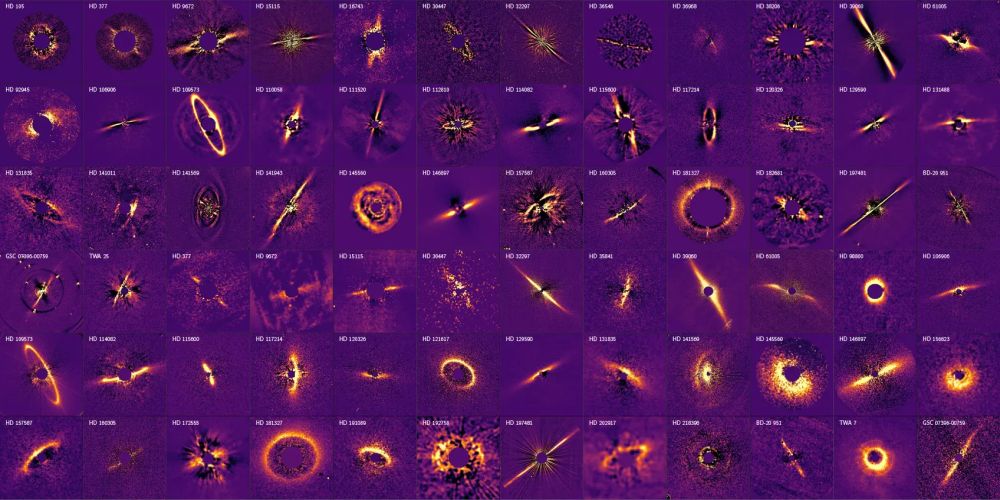

"To obtain this collection, we processed data from observations of 161 nearby young stars whose infrared emission strongly indicates the presence of a debris disk," said lead author Engler in a press release. "The resulting images show 51 debris disks with a variety of properties — some smaller, some larger, some seen from the side and some nearly face-on – and a considerable diversity of disk structures. Four of the disks had never been imaged before."

The data shows that more massive stars have more dust. It also shows that debris disks have more dust the further they are from their stars. But the most interesting result is the structures in the dust rings.

Many of the rings share similarities with our Solar System. They have concentric ring-like structures where disk material is predominantly found at specific distances from the star. This mirrors the main asteroid belt and the Kuiper Belt.

The belt structures are also associated with planets. Giant planets in these systems, some of which have already been observed, are carving out gaps in these ring structures. Some of the features in the disks, like sharp edges, also hint at the presence of undiscovered planets.

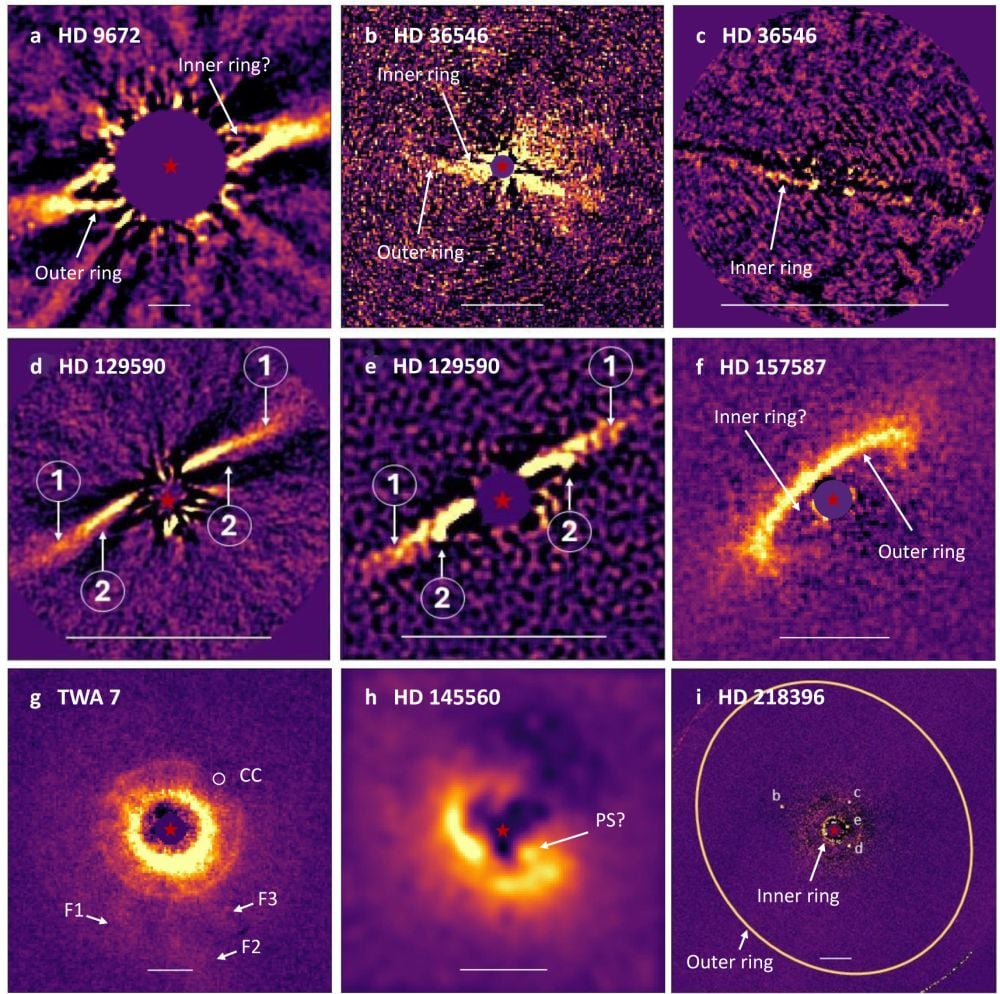

The researchers used dynamical modelling to probe the relationship between debris disks and planetary architecture. In systems where the disks were resolved, they were able to estimate the masses and the semi-major axes of planets that would be able to carve gaps and the inner edges of belts. "For single-belt systems, planets capable of shaping the inner edges span masses from 0.1 to 13 Jupiter masses, with orbital radii consistent with observed disk edges," they explain.

In systems with two belts, the modelling showed that planets with sub-Jovian masses were able to create the gaps, but are also below the threshold of detection. "These findings imply that Neptune- to sub-Saturn-mass planets at tens to hundreds of au may be common but remain undetected," the authors explain.

*This figure from the research shows images of debris disks with signs of multiple rings. Red asterisks mark the positions of the stars. Image Credit: © N. Engler et al./SPHERE Consortium/ESO*

*This figure from the research shows images of debris disks with signs of multiple rings. Red asterisks mark the positions of the stars. Image Credit: © N. Engler et al./SPHERE Consortium/ESO*

Ultimately, this research shows that our Solar System's architecture is not much different from most of these systems.

"... a comparison of planetary architectures shows that most benchmark systems resemble the Solar System, with multiple planets located inside wide Kuiper-belt analogues," the authors write in their research article. "Dynamical modeling further indicates that many observed gaps and inner edges can be explained by unseen planets below current detection thresholds, typically with Neptune- to sub-Jovian masses, underscoring the likely ubiquity of such planets in shaping debris disk morphologies," they conclude.

Future observations of these systems with telescopes like the JWST and ALMA should refine the results.

"Expanding such multiwavelength approaches, together with advancements in disk modeling techniques, is essential for refining our understanding of debris disk evolution and the architectures of planetary systems," the authors conclude.

Universe Today

Universe Today