With the astronauts of the SpaceX Crew-11 mission safely home, NASA is moving ahead with preparations for the launch of the Crew-12 mission. The crew will launch for the International Space Station (ISS) no sooner than Wednesday, Feb. 11th. It will consist of NASA astronauts Jessica Meir (commander) and Jack Hathaway (pilot), ESA astronaut Sophie Adenot (mission specialist), and Russian cosmonaut Andrey Fedyaev (mission specialist). Once they reach the ISS, select crew members will participate in human health studies designed to assess how astronauts' bodies adapt to long periods spent in space.

The long-term effects of microgravity on the human body are well-documented thanks to long-duration studies conducted aboard the ISS. The most well-known symptoms include bone density loss, muscle atrophy, changes in circulation and vision, and alterations in the cardiovascular and nervous systems. Comparative studies, such as NASA's Twin Study, have also revealed that genetic changes can occur, underscoring the need for further research. If humans are to return to the Moon (this time to stay), spend extended periods in deep space, and explore Mars, the physiological effects must be understood and treatments prepared.

The new study, called Venous Flow, will examine whether time aboard the ISS increases the likelihood of crew members developing blood clots. Blood flow patterns change in microgravity, causing more blood and bodily fluids to rush toward the head. Under these circumstances, blood clots could pose a serious health risk, including increased risks of stroke, heart attack, pulmonary embolism, and deep vein thrombosis (DVT). These studies will be overseen by NASA's Human Research Program (HRP) and will involve astronauts undergoing ultrasound imaging of their blood vessels to examine alterations in their circulatory patterns.

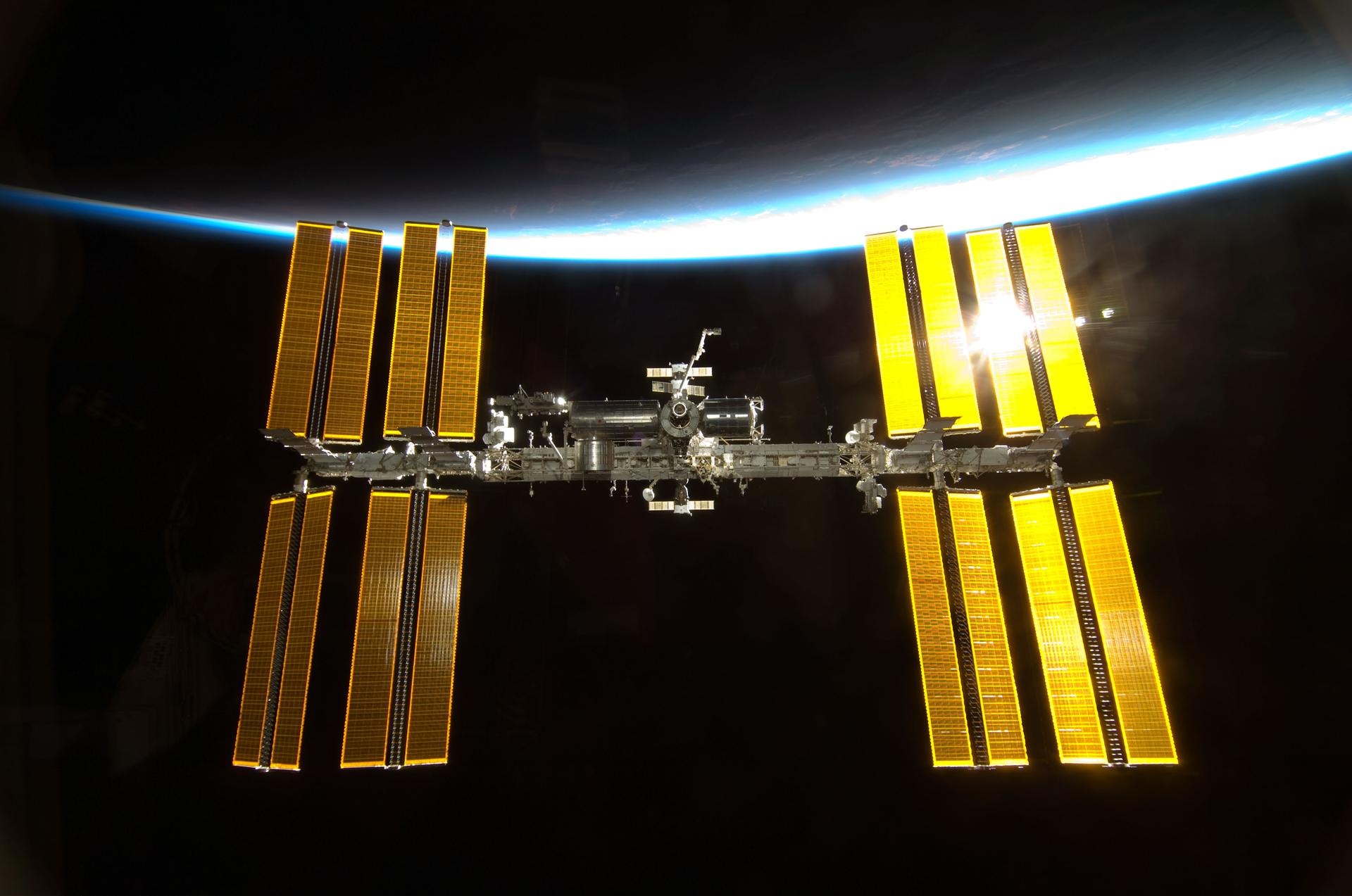

*The International Space Station in Earth orbit. Credit: NASA*

*The International Space Station in Earth orbit. Credit: NASA*

They will also simulate a lunar landing to assess the disorientation that occurs during gravitational transitions. This refers to the process where astronauts transition from microgravity to the lower-gravity environments of the Moon and Mars - approximately 16.5% and 38% of Earth's gravity, respectively. The crew will undergo preflight and postflight MRIs, ultrasound scans, blood draws, and blood pressure checks. During the flight, crew members will perform their own jugular vein ultrasound examinations, do BP checks, and draw blood samples for analysis back on Earth.

“Our goal is to use this information to better understand how fluid shifts affect clotting risk, so that when astronauts go on long-duration missions to the Moon and Mars, we can build the best strategies to keep them safe,” said Dr. Jason Lytle, a physiologist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center who is leading the study.

Another study, Manual Piloting, will assess the astronaut's piloting and decision-making skills. While spacecraft landings on the Moon and Mars are expected to be automated, crews must be prepared to take over and pilot the vehicle if necessary. During this study, select crew members will perform multiple simulated Moon landings towards the Moon's South Pole-Aitken Basin, where the Artemis III and future missions intend to explore and even establish a base of operations. Said Dr. Scott Wood, a neuroscientist at NASA Johnson who is coordinating the investigation:

Astronauts may experience disorientation during gravitational transitions, which can make tasks like landing a spacecraft challenging. This study will help us examine astronauts’ ability to operate a spacecraft after adapting from one gravity environment to another, and whether training near the end of their spaceflight can help prepare crews for landing. We’ll monitor their ability to manually override, redirect, and control a vehicle, which will guide our strategy for training Artemis crews for future Moon missions.

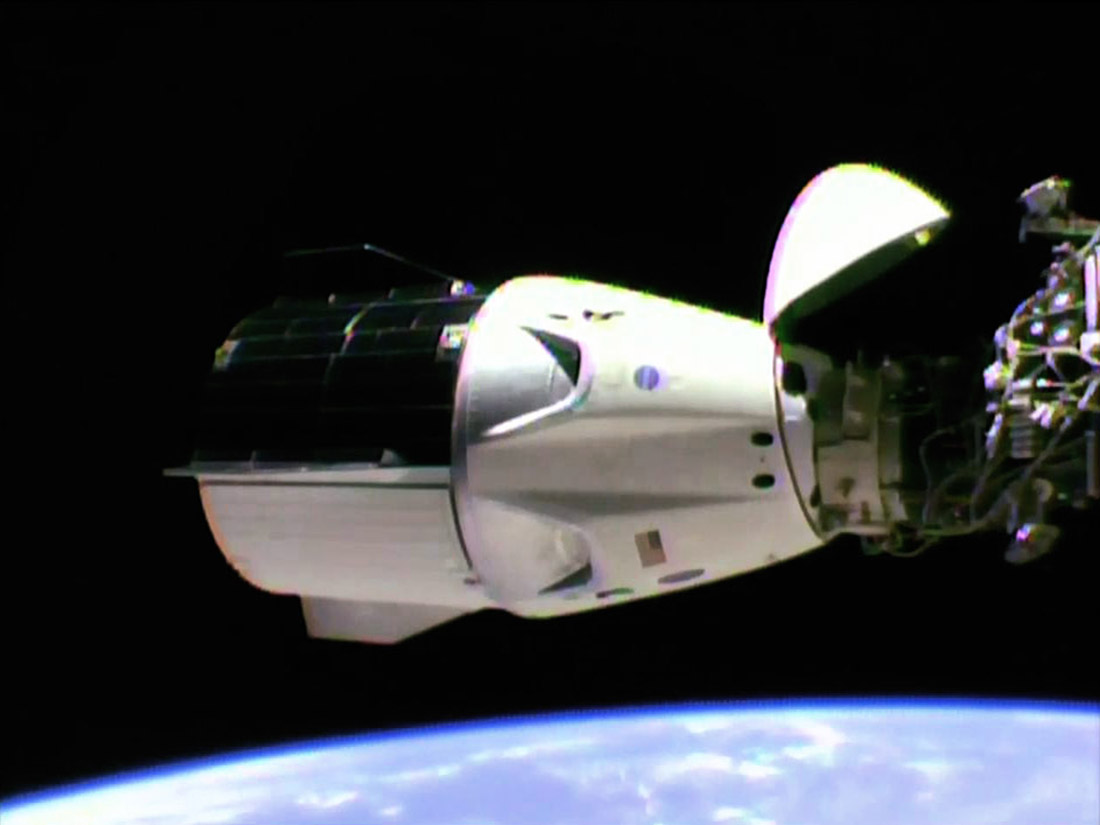

*The SpaceX Crew Dragon is docked to the station’s international docking adapter, which is attached to the forward end of the Harmony module. Credit: NASA TV*

*The SpaceX Crew Dragon is docked to the station’s international docking adapter, which is attached to the forward end of the Harmony module. Credit: NASA TV*

This study will also assess how the risk of disorientation from gravitational transitions increases the longer astronauts have spent in space. This is a major concern for crewed missions to Mars, where astronauts who have spent six to nine months in microgravity will need to transition to a planet with a significant fraction of Earth's gravity. For this run, which debuted with the Crew-11 mission, researchers plan to recruit seven astronauts for short-duration missions (up to 30 days) and 14 for long-duration missions (up to 106 days).

The risk of astronauts experiencing disorientation from gravitational transitions increases the longer they’re in space. For this study, which debuted during the agency’s SpaceX Crew-11 mission, researchers plan to recruit seven astronauts for short-term private missions lasting up to 30 days and 14 astronauts for long-duration missions lasting at least 106 days. Meanwhile, a control group will perform the same tasks to provide a basis of comparison. Another study will investigate potential treatment for vision and eyesight issued caused by microgravity, known as spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS).

Finally, select crew members will participate in a study to document injuries that occur during landing and the transition to Earth's gravity. The risk of injury dramatically increases as crews complete the final leg of their mission and splashdown in Earth's oceans. This last test will inform improved spacecraft design and safety features that protect astronauts from landing forces. The results of these tests will inform NASA's planning for extended stays in space and for future exploration missions, including the Artemis Program, the Moon-to-Mars mission architecture, and long-duration missions aboard future space stations.

Further Reading: NASA

Universe Today

Universe Today