The early stage of giant telescope development involves a lot of horse-trading to try to appease all the different stakeholders that are hoping to get what they want out of the project, but also to try to appease the financial managers that want to minimize its cost. Typically this horse-trading takes the form of a series of white papers that describe what would be needed to meet the stated objectives of the mission and suggest the type of instrumentation and systems that would be needed to achieve them. One such white paper was recently released by the Living Worlds Working Group, which is tasked with speccing out the Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO), one of the world’s premiere exoplanet hunting telescopes that is currently in the early development stage. Their argument in the paper, which is available in pre-print on arXiv, shows that, in order to meet the objectives laid out in the recent Decadal survey that called for the telescope, it must have extremely high signal-to-noise ratio, but also be able to capture a very wide spectrum of light.

Those may sound like obvious desires for any telescope working group - more light and higher signal resolution are great no matter what you’re looking for. But, in HWO’s case, there are some very specific features of habitable exoplanets that it will be looking for that require such broad capabilities.

Its capabilities will be based around its ability to directly image exoplanets, which contrasts with other large telescopes, such as the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). JWST usually looks at planetary “transits” - when a planet crosses in front of its star - to analyze its atmosphere. HWO, on the other hand, will use a technology called a coronagraph to block out a host star’s light and directly image the planet. This will allow it to not only see the planet’s atmosphere, but also parts of its surface - as long as the signal to noise ratio of its instruments are high enough.

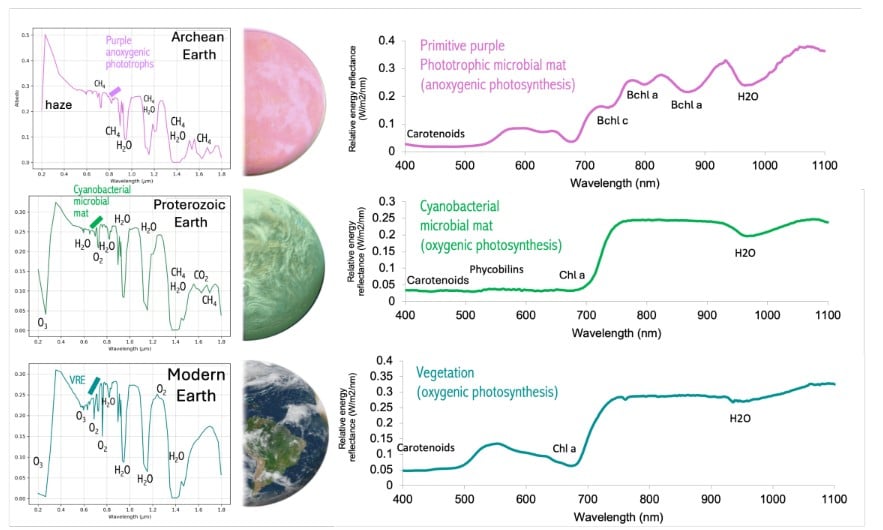

NASA describes the Habitable Worlds Observatory. Credit - NASA Goddard YouTube ChannelSo what should it be looking for on the surface? In remote sensing, there is a standard called the “Vegetation Red Edge”, which shows plants absorbing red light, but strongly reflecting near-infrared light to keep from overheating. This is very noticeable in spectroscopy with a vertical line right at that edge between red and near-infrared. However, that line will only exist if the system is capable of capturing both visible and near-infrared light.

Other colors are thought to have played a major role in past life on Earth as well, and they might also be seen from afar using HWO. One intriguing case is the use of Bacteriochlorophylls for photosynthesis. Known as purple anoxygenic phototrophs, these early lifeforms were thought to use retinal pigments, similar to those used in our eye’s vision protein, to absorb green light for use in photosynthesis and reflect red and blue light, which would have made them appear purple. Descendants of these early bacteria still exist today - primarily as Halobacteria, which are known for turning water in salt flats a vibrant purple/pink. Notably, they absorb light well into the infrared, so if HWO looks only at visible light, it would completely miss the tell-tale signs of this phase of development of life on Earth, which scientists think might have lasted for almost 1.5 billion years.

After the purple bacteria phase came a much more common sight on modern Earth’s surface - chlorophyll. Plant life on the surface of a planet would be most notable via the “Red Edge” discussed above, but there is another, more recent suggestion of a reason we would find green on an exoplanet's surface.

SciShow Space episode about Purple Planets. Credit - SciShow Space YouTube ChannelRecently, researchers have put forward the “Green Ocean” hypothesis. Their theory is that, between 4 and 2.5 billion years ago, hydrothermal vents were spewing up huge amounts of ferrous iron into the ocean. This iron absorbed blue/red light, but reflected green, essentially turning the oceans green. Cyanobacteria, one of the dominant life forms of that age, then developed pigments known as phycobilins to harvest the green light the ocean was reflecting. This would look very similar to plants themselves, making it difficult to differentiate between plants and ocean-covering cyanobacteria. Given that both are clear signs of life, it might not matter.

But ultimately, there are other, non-biological processes that could give off the same signals. Iron oxide itself is noticeable from what's known as a “red slope” in spectroscopy, where the rust reflects red light. With low-resolution instruments, it can look strikingly similar to the “Red Edge” that is indicative of vegetation or cyanobacteria, so ensuring HWO has high enough resolution to differentiate something like Mars from a world covered in plants is a key engineering goal.

Another non-biological “mimic” in remote spectroscopy is cinnabar (mercury sulfide); it has a strong “edge” at 600 nm, which contrasts to the strong edge at 700 nm for vegetation. While this might not be common on potentially habitable worlds, it’s still worth noting that HWO will have to be able to distinguish the sharp lines of vegetation from the sharp lines of this lifeless rock. Similarly, elemental sulfur has another “edge” even further up the spectroscopic scale. This one, which happens between 450 and 500 nm, is easier to differentiate from vegetation, but still worth noting due to the possibility that low-resolution instrumentation could confuse some combination of this and cinnabar as something biological.

Ultimately, and to probably nobody’s surprise, the Working Group tasked with developing the HWO wants as high of a resolution in as wide a range as possible. Whether or not the budgetary committee will go for that expense remains to be seen. Given the recent cuts to prominent NASA programs, it seems unlikely. But hopefully the Working Group will get what it wants, and HWO will be able to differentiate between Green Ocean, Purple Bacteria, ground-covering forests, and massive amounts of cinnabar.

Learn More:

N. Parenteau et al. - Habitable Worlds Observatory Living Worlds Working Group: Surface Biosignatures on Potentially Habitable Exoplanets

UT - HWO Could Find Irrefutable Signs Of Life On Exoplanets

UT - Is the Habitable Worlds Observatory a Good Idea?

UT - The Habitable Worlds Observatory Could Find More Very Massive Stars

Universe Today

Universe Today