Fans of the Star Wars franchise will surely remember the iconic scene where Luke Skywalker steps out of his uncle and aunt's home on Tatooine to contemplate his future. Looking to the far horizon, wondering if he will ever get off that desolate desert planet, he gazes upon two setting suns. Naturally, some purists (like myself) would be quick to point out that Lucas "borrowed" this idea from the late and great Frank Herbert (creator of the Dune franchise). Nevertheless, the scene masterfully illustrates why Tatooine is a hostile, unforgiving planet where the indigenous inhabitants are nomads or salvagers, and the primary industry is "moisture farming."

But such speculation that there could be planets in our galaxy that orbit two stars goes beyond the realm of science fiction. For starters, binary star systems are very common, accounting for roughly one-third to one-half of all star systems in the Milky Way. Moreover, most stars currently in our galaxy are believed to have formed in pairs and lost their companions over time due to gravitational interactions. Still, of the roughly 4,500 stars known to have exoplanets orbiting them, very few have planets that orbit two stars. This begs the question: of the 6,100 exoplanets that have been confirmed to date, why do only 14 orbit binary pairs?

According to two astrophysicists from the University of California, Berkeley and the American University of Beirut, it appears that Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity is to blame. Mohammad Farhat, a Miller Postdoctoral Fellow at UC Berkeley, led the research with the assistance of Jihad Touma, a physics professor at the American University of Beirut. Their findings were published in a study titled "Capture into Apsidal Resonance and the Decimation of Planets around Inspiraling Binaries," which appeared on Dec. 8th in *The Astrophysical Journal Letters*.

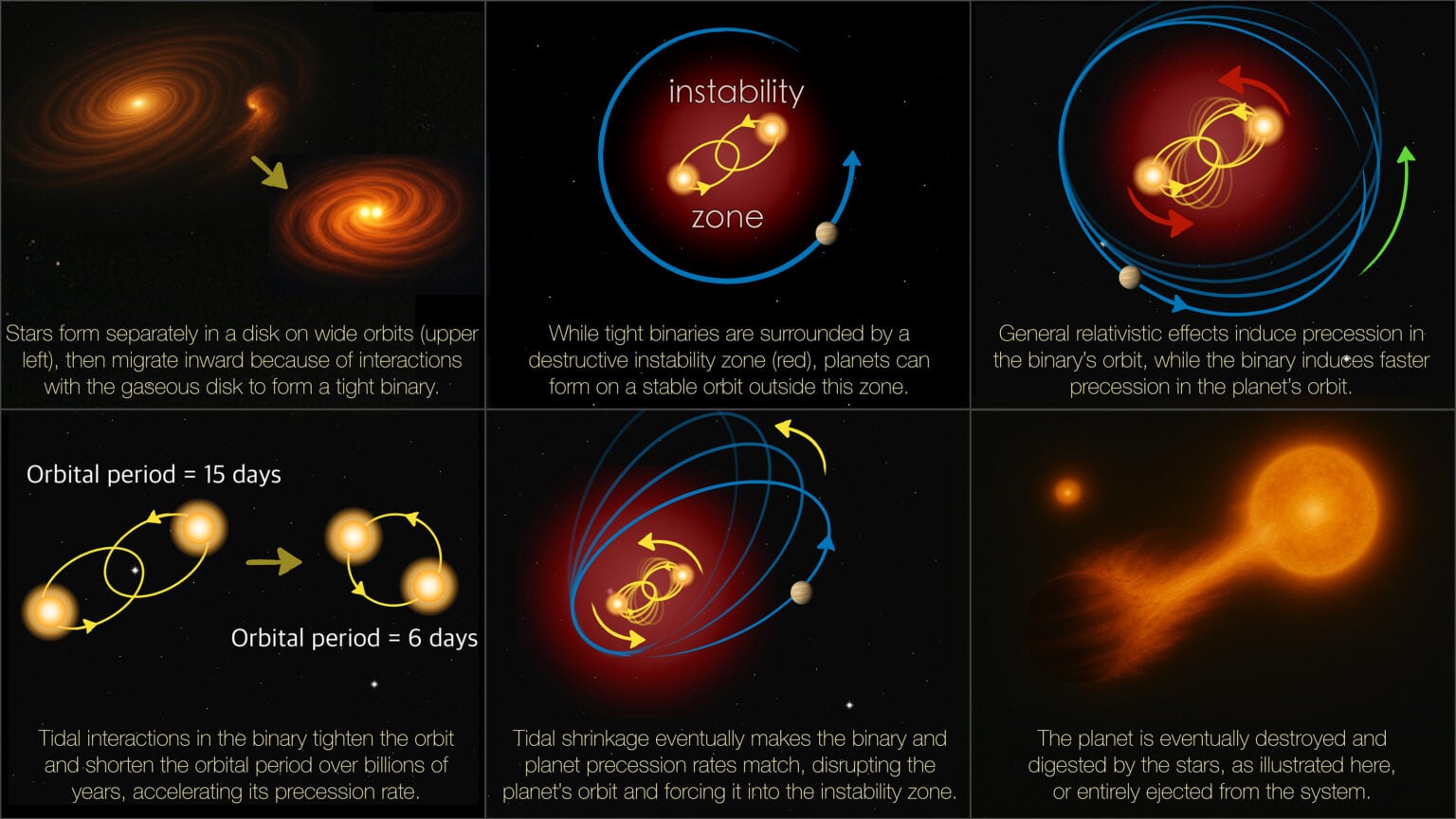

*A step-by-step explanation for why planets that orbit a double star eventually enter an unstable orbit and disappear from the system. Credit: Mohammad Farhat/UC Berkeley*

*A step-by-step explanation for why planets that orbit a double star eventually enter an unstable orbit and disappear from the system. Credit: Mohammad Farhat/UC Berkeley*

The Kepler and TESS missions, which were responsible for discovering the majority of confirmed exoplanets to date, detected exoplanets using the Transit Method - where periodic dips in a star's brightness are seen as an indication of an orbiting planet. However, Kepler also found about 3,000 eclipsing binary stars during its observations, in which one of the pair passes in front of the other. Given that 10% of single Sun-like stars were found to have massive planets, astronomers expected to see the same percentage around binary pairs (roughly 300).

However, only 47 exoplanet candidates were found around binary stars, and only 14 have been confirmed as transiting circumbinary planets. Said Farhat in a UC Berkeley News release:

You have a scarcity of circumbinary planets in general, and you have an absolute desert around binaries with orbital periods of seven days or less. The overwhelming majority of eclipsing binaries are tight binaries and are precisely the systems around which we most expect to find transiting circumbinary planets.

Farhat and Touma previously collaborated on studies examining the formation and evolution of planetary orbits in various types of stellar systems. Ten years ago, Touma began to consider how the orbits of binary black holes and binary stars affected the orbits of planets around them. After examining the exoplanet census, he developed a theory in which gravitational forces and the way co-orbiting stars spiral in toward each other might explain the "missing" planets around tight binaries. First proposed in 1915 by Albert Einstein, the Theory of General Relativity (GR) describes how massive objects alter the curvature of spacetime around them.

His interpretation explained various astronomical phenomena, including Mercury's precession of perihelion in its orbit. In essence, this means that Mercury's elliptical orbit changed orientation over time, with its closest point (perihelion) rotating around the Sun. While classical Newtonian physics could not account for this behavior, Einstein's theory accurately predicted it. The same effect applies to any two objects orbiting closely to each other, like a binary pair. Most binary star systems consist of two stars of comparable mass that circle each other in an elliptical orbit.

Astronomers theorize that these pairs form far apart, but move closer to each other over eons due to interactions with the surrounding gas from which they formed. This causes tidal interactions that, over billions of years, will further shrink their orbit until their orbital period is about a week or less. When this occurs, the point at which the two stars make their closest approach (periastron) will precess. For a planet orbiting a binary pair, the gravitational pull of both stars also causes the planet's orbital axis to precess.

But as the binary pair gets closer to each other in their orbit, their precession rate will increase while the precession rate for the planet will slow. When the two rates match up (known as resonance), the planet's orbit elongates considerably, taking it much farther at aphelion (its farthest point) and bringing it closer at perihelion (its closest point). Using mathematical and computer models, Farhat and Touma found that GR effects disrupt eight of every 10 exoplanets around tight binaries, and 75% of these would be destroyed in the process.

This arises from the instability zone around binary stars, where three-body interactions between the pair and a planet lead to the planet's loss. As their calculations showed, once the stars and planet reach a state of resonance, the exoplanet’s orbit will elongate, and its perihelion will draw closer to the instability zone. When the point of periastron enters the zone of instability, the exoplanet is either exiled to the far reaches of the system or approaches too close to the binary and is engulfed. Said Farhat:

Two things can happen: Either the planet gets very, very close to the binary, suffering tidal disruption or being engulfed by one of the stars, or its orbit gets significantly perturbed by the binary to be eventually ejected from the system. In both cases, you get rid of the planet. Planets form from the bottom up, by sticking small-scale planetesimals together. But forming a planet at the edge of the instability zone would be like trying to stick snowflakes together in a hurricane.

"A planet caught in resonance finds its orbit deformed to higher and higher eccentricities, precessing faster and faster while staying in tune with the orbit of the binary, which is shrinking," added Touma. "And on the route, it encounters that instability zone around binaries, where three-body effects kick into place and gravitationally clear out the zone."

*A still from the original Star Wars film, showing Luke Skywalker observing a double sunset on Tatooine. Credit: Lucasfilm/20th Century Fox*

*A still from the original Star Wars film, showing Luke Skywalker observing a double sunset on Tatooine. Credit: Lucasfilm/20th Century Fox*

Because this disruption occurs over only a few tens of millions of years, the process is brief by cosmological standards, which explains why exoplanets around tight binaries are very rare. The Kepler and TESS data certainly supports their findings, as none of the 14 confirmed exoplanets in binary systems are located around tight binaries with periods of less than ~7 days. Furthermore, 12 of these were found just beyond the edge of the system's instability zone, which would have likely migrated since it would be very difficult for planets to form there.

This doesn’t mean that binary stars don’t have planets that orbit both stellar companions. But those that are not ejected, destroyed by tidal disruption, or engulfed are likely too far from their stars to be detectable using the Transit Method. Currently, the researchers are employing their models to determine how GR affects clusters of stars around pairs of supermassive black holes. In a more speculative vein, they are also investigating whether GR can partially explain the dearth of planets around binary pulsars. As Touma noted, their research shows how Einstein's revolutionary theories are still vital to our understanding of the cosmos:

Interestingly enough, nearly a century following Einstein’s calculations, computer simulations showed how relativistic effects may have saved Mercury from chaotic diffusion out of the solar system. Here we see related effects at work disrupting planetary systems. General relativity is stabilizing systems in some ways and disturbing them in other ways.

Further Reading: UC Berkley News

Universe Today

Universe Today