[/caption]

For years, scientists have been trying to replicate the type of nuclear fusion that occurs naturally in stars in laboratories here on Earth in order to develop a clean and almost limitless source of energy. This week, two different research teams report significant headway in achieving inertial fusion ignition—a strategy to heat and compress a fuel that might allow scientists to harness the intense energy of nuclear fusion. One team used a massive laser system to test the possibility of heating heavy hydrogen atoms to ignite. The second team used a giant levitating magnet to bring matter to extremely high densities — a necessary step for nuclear fusion.

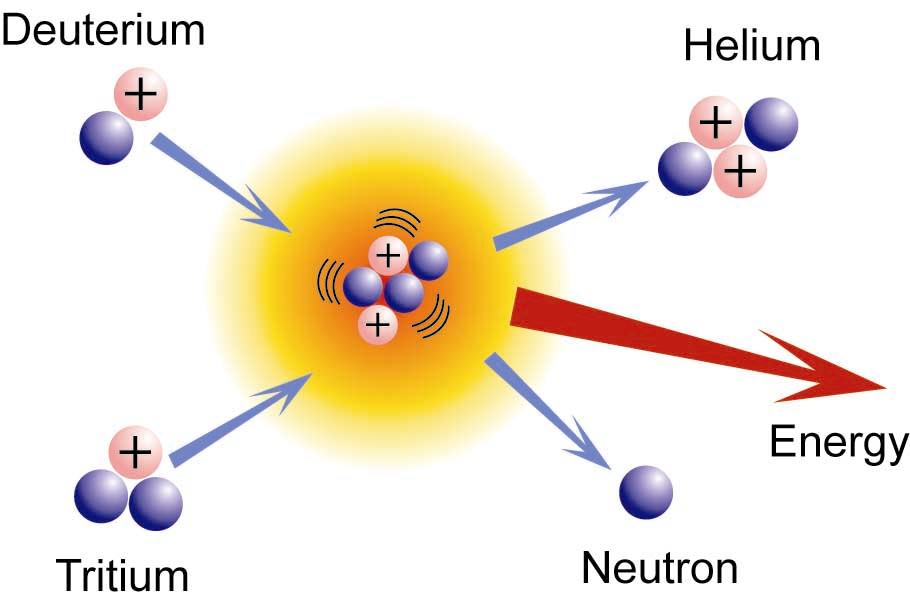

Unlike nuclear fission, which tears apart atoms to release energy and highly radioactive by-products, fusion involves putting immense pressure, or "squeezing" two heavy hydrogen atoms, called deuterium and tritium together so they fuse. This produces harmless helium and vast amounts of energy.

Recent experiments at the National Ignition Facility in Livermore, California used a massive laser system the size of three football fields. Siegfried Glenzer and his team aimed 192 intense laser beams at a small capsule—the size needed to store a mixture of deuterium and tritium, which upon implosion, can trigger burning fusion plasmas and an outpouring of usable energy. The researchers heated the capsule to 3.3 million Kelvin, and in doing so, paved the way for the next big step: igniting and imploding a fuel-filled capsule.

In a second report released earlier this week, researchers used a Levitated Dipole Experiment, or LDX, and suspended a giant donut-shaped magnet weighing about a half a ton in midair using an electromagnetic field. The researchers used the magnet to control the motion of an extremely hot gas of charged particles, called a plasma, contained within its outer chamber.

The donut magnet creates a turbulence called "pinching" that causes the plasma to condense, instead of spreading out, which usually happens with turbulence. This is the first time the "pinching" has been created in a laboratory. It has been seen in plasma in the magnetic fields of Earth and Jupiter.

A much bigger ma LDX would have to be built to reach the density levels needed for fusion, the scientists said.

Paper:

Symmetric Inertial Confinement Fusion Implosions at Ultra-High Laser Energies

Sources:

Science Magazine,

LiveScience

Universe Today

Universe Today