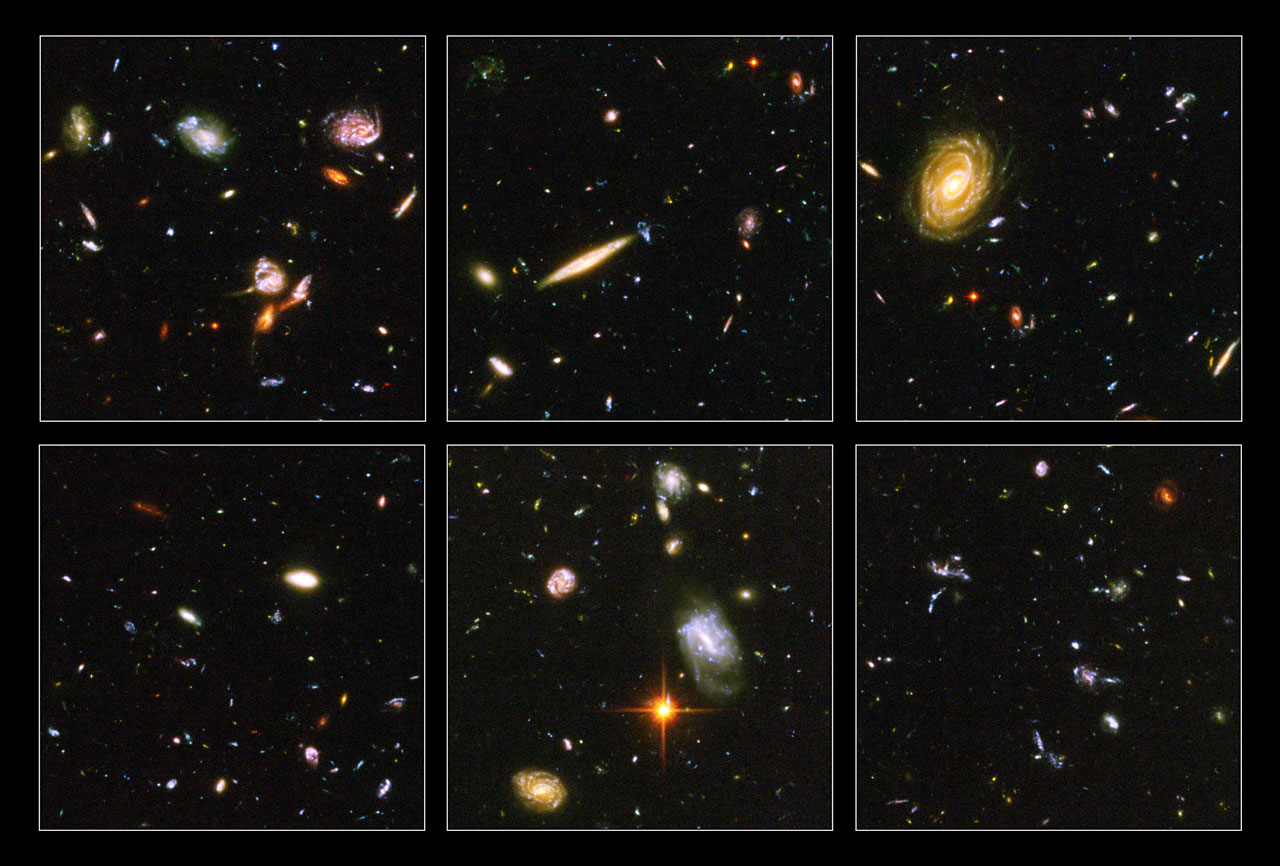

Since its deployment in 1990, the

Hubble Space Telescope

has given us some of the richest and most detailed images of our Universe. Many of these images were taken while observing a patch of sky located in the

Fornax constellation

between September 2003 and January 2004. This region, known as the

Hubble Ultra Deep Field

(HUDF), contains an estimated 10,000 galaxies, all of which existed roughly 13 billion years ago.

Looking to this region of space, multiple teams of astronomers used the MUSE instrument on the ESO's

Very Large Telescope

(VLT) to discover 72 previously unseen galaxies. In a series of

ten recently released studies

, these teams indicate how they measured the distance and properties of 1600 very faint galaxies in the Ultra Deep Field, revealing new information about star formation and the motions of galaxies in the early Universe.

The original

HUDF images

, which were published in 2004, were a major milestone for astronomy and cosmology. The thousands of galaxies it observed were dated to less than just a billion years after the Big Bang, ranging from 400 to 800 million years of age. This area was subsequently observed many times using the Hubble and other telescopes, which has resulted in the deepest views of the Universe to date.

One such telescope is the

European Southern Observatory

's (ESO) Very Large Telescope, located in the

Paranal Observatory

in Chile. Intrinsic to the studies of the HUDF was the

Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer

(MUSE), a panoramic integral-field spectrograph operating in the visible wavelength range. It was the data accumulated by this instrument that allowed for 72 new galaxies to be discovered from this tiny area of sky.

The MUSE HUDF Survey team, which was led by Roland Bacon of the

Centre de recherche astrophysique de Lyon

(CRAL) and the

National Center for Scientific Research

(CNRS), included members from multiple European observatories, research institutes and universities. Together, they produced ten studies detailing the precise spectroscopic measurements they conducted of 1600 HUDF galaxies.

This was an unprecedented accomplishment, given that this is ten times as many galaxies that have had similar measurements performed on them in the last decade using ground-based telescopes. As Bacon indicated in an ESO

press release

:

" MUSE can do something that Hubble can’t — it splits up the light from every point in the image into its component colors to create a spectrum. This allows us to measure the distance, colors and other properties of all the galaxies we can see — including some that are invisible to Hubble itself. "

The galaxies detected in this survey were also 100 times fainter than any galaxies studied in previous surveys. Given their age and their very dim and distant nature, the study of these 1600 galaxies is sure to add to any already very richly-observed field. This,in turn, can only deepen our understanding of how galaxies formed and evolved during the past 13 billions years.

The 72 newly-discovered galaxies that the survey observed are known as Lyman-alpha emitters, a class of galaxy that is extremely distant and only detectable in Lyman-alpha light. This form of radiation is emitted by excited hydrogen atoms, and is thought to be the result of ongoing star formation. Our current understanding of star formation cannot fully explain these galaxies, and they were not visible in the original Hubble images.

Thanks to MUSE's ability to disperse light into its component colors, these galaxies became more apparent. As Jarle Brinchmann - an astronomer at the University of Leiden and the University of Porto's (CAUP) Institute of Astrophysics and Space Sciences, and the lead author of one of the papers - described the results of the survey:

" MUSE has the unique ability to extract information about some of the earliest galaxies in the Universe — even in a part of the sky that is already very well studied. We learn things about these galaxies that is only possible with spectroscopy, such as chemical content and internal motions — not galaxy by galaxy but all at once for all the galaxies! "

Another major finding of this survey was the systematic detection of luminous hydrogen halos around galaxies in the early Universe. This finding is expected to give astronomers a new and promising way to study how material flowed in and out of early galaxies, which was central to early star formation and galactic evolution. The series of studies produced by Bacon and his colleagues also indicate a range of other possibilities.

These include studying the role faint galaxies played during cosmic reionization, the period that took place between 150 million to billion years after the Big Bang. It was during this period, which followed the "dark ages" (380 thousand to 150 million years ago) that the first stars and quasars formed and sent ionizing radiation throughout the early Universe. And as Roland Bacon explained, the best may yet be to come:

" Remarkably, these data were all taken without the use of MUSE’s recent Adaptive Optics Facility upgrade. The activation of the AOF after a decade of intensive work by ESO’s astronomers and engineers promises yet more revolutionary data in the future."

Even before Einstein proposed his groundbreaking

Theory of General Relativity

- which established that space and time are inextricably linked - scientists have understood that probing deeper into the cosmic field is to also probe farther back in time. The farther we are able to see, the more we are able to learn about how the Universe evolved over the course of billions of years.

Further Reading: ESO

Universe Today

Universe Today