In accordance with the

Nebular Hypothesis

, the Solar System is believed to have formed through the process of accretion. Essentially, this began when a massive cloud of dust and gas (aka. the Solar Nebula) experienced a gravitational collapse at its center, giving birth to the Sun. The remaining dust and gas then formed into a protoplanetary disc around the Sun, which gradually coalesced to form the planets.

However, much about the process of how planets evolved to become distinct in their compositions has remained a mystery. Luckily,

a new study

by a team of researchers from the University of Bristol has approached the subject with a fresh perspective. By examining a combination of Earth samples and meteorites, they have shed new light on how planets like Earth and Mars formed and evolved.

The study, titled "

Magnesium Isotope Evidence that Accretional Vapour Loss Shapes Planetary Compositions

", recently appeared in the scientific journal

Nature.

Led by

Remco C. Hin, a senior research associate from the

School of Earth Sciences

at the University of Bristol, the team compared samples of rock from Earth, Mars, and the Asteroid Vesta to compare the levels of magnesium isotopes within them.

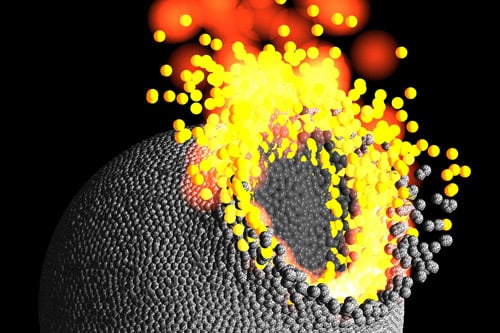

[caption id="attachment_121982" align="aligncenter" width="525"]

Artist's impression of the early Solar System, where collision between particles in an accretion disc led to the formation of planetesimals and eventually planets. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

[/caption]

Their study attempted answering what has been a lingering question in the scientific community - i.e. did the planets form the way they are today, or did they acquire their distinctive compositions over time? As Dr. Remco Hin explained in a University of Bristol

press release

:

"

To break it down, accretion consists of clumps of material colliding with neighboring clumps to form larger objects. This process is very chaotic, and material is often lost as well as accumulated due to the extreme heat generated by these high-speed collisions. This heat is also believed to have created oceans of magma on the planets as they formed, not to mention temporary atmospheres of vaporized rock.

Until planets become about the same size as Mars, their force of gravitational attraction was too weak to hold onto these atmospheres. And as more collisions took place, the composition of these atmosphere and of the planets themselves would have changes substantially. How exactly the terrestrial planets - Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars - obtained their current, volatile-poor compositions over time is what scientists have hoped to address.

[caption id="attachment_47332" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Artist impression of the Late Heavy Bombardment period. Credit: NASA

[/caption]

For example, some believe that the planets current compositions are the result of particular combinations of gas and dust during the earliest periods of planet formation - where terrestrial planets are silicate/metal rich, but volatile poor, because of which elements were most abundant closest to the Sun. Others have suggested that their current composition is a consequence of their violent growth and collisions with other bodies.

To shed light on this, Dr. Hin and his associates analyzed samples of Earth, along with meteorites from Mars and the asteroid Vesta using a new analytical approach. This technique is capable of obtaining more accurate measurements of magnesium isotope rations than any previous method. This method also showed that all differentiated bodies - like Earth, Mars and Vesta - have isotopically heavier magnesium compositions than chondritic meteorites.

From this, they were able to draw three conclusions. For one, they found that Earth, Mars and Vesta have distinct magnesium isotope rations that could not be explained by condensation from the Solar Nebula. Second, they noted that the study of heavy magnesium isotopes revealed that in all cases, the planets lost about 40% percent of their mass during their formation period, following repeated episodes of vaporization.

Last, they determined that the accretion process results in other chemical changes that generate the unique chemical characteristics of Earth. In short, their study showed that Earth, Mars and Vesta all experiences significant losses of material after formation, which means that their peculiar compositions were likely the result of collisions over time. As Dr Hin added:

Their study also indicated that this violent formation process could be characteristic of planets in general. These findings are not only significant when it comes to the formation of the Solar System, but of extra-solar planets as well. When it comes time to explore distant star systems, the distinctive compositions of their planets will tell us much about the conditions from which they formed, and how they came to be.

Further Reading: University of Bristol

,

Nature

Universe Today

Universe Today