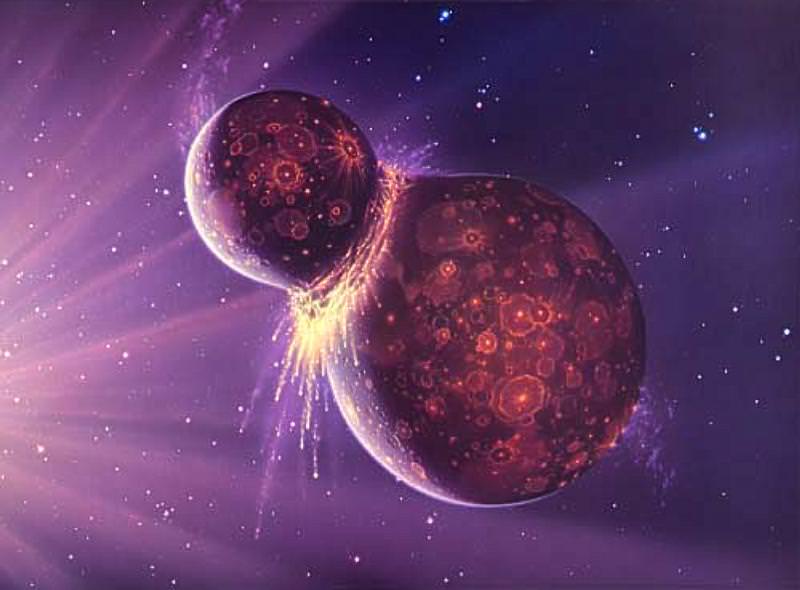

Image courtesy Joe Tucciarone

One of the leading theories for how our Moon formed is the Giant Impactor Theory, which proposes a small planet about the size of Mars struck Earth early in our solar system's formation, ejecting large volumes of heated material from the outer layers of both objects. This formed a disk of orbiting material which eventually stuck together to form the Moon. Until now there's been no way to actually test this theory. But a new instrument that closely examines iron isotopes could possibly shed insight into the origin of the moon, as well as how Earth and the other terrestrial planets formed.

The new instrument, a plasma source mass spectrometer separates ions (charged particles) according to their masses and allows for a close examination of iron isotopes. Looking at the slight variations iron displays at the subatomic level can tell planetary scientists more about the formation of crust than previously thought, according to Nicolas Dauphas from the University of Chicago, Fang-Zhen Teng of the University of Arkansas and Rosalind T. Helz of the U.S. Geological Survey who co-authored a paper that will be published in the journal

Science.

Their findings contradicts the widely held view that isotopic variations occur only at relatively low temperatures, and only in lighter elements, such as oxygen. But Dauphas and his associates were able to measure isotopic variations as they occur in magma at temperatures of 1,100 degrees Celsius (2,012 degrees Fahrenheit).

Previous studies of basalt found little or no separation of iron isotopes, but those studies focused on the rock as a whole, rather than its individual minerals. "We analyzed not only the whole rocks, but the separate minerals," Teng said. In particular, they analyzed olivine crystals.

Inside the instrument, the ions are formed in a plasma of argon gas at a temperature of nearly 14,000 degrees Fahrenheit (8,000 degrees Kelvin, hotter than the sun's surface).

The instrument was tested on the lava of Kilauea Iki crater in Hawaii.

If applied to a variety of terrestrial and extraterrestrial basalts, including moon rocks, meteorites from Mars and the asteroids, the method could provide more definitive evidence for a the Giant Impactor Theory, and provide clues the formation of Earth's continents, and could potentially tell us more about how other planetary bodies formed.

"Our work opens up exciting avenues of research," Dauphas said. "We can now use iron isotopes as fingerprints of magma formation and differentiation, which played a role in the formation of continents."

Original News Source:

PhysOrg

Universe Today

Universe Today