Extreme solar storms are a relatively rare event. However, as more and more of our critical infrastructure moves into space, they will begin to have more and more of an impact on our daily lives, rather than just providing an impressive light show at night. So it's best to know what's coming, and a new paper from an international team of researchers led by Kseniia Golubenko and Ilya Usoskin of the University of Oulu in Finalnd found a massive Extreme Solar Particle Event (ESPE) that happened 12350 years ago, which is now considered to be the most energetic on record.

During an ESPE, the Sun releases a stream of particles that collide with Earth's atmosphere. This type of event isn't the same as probably the most famous "solar storm" of all time, the Carrington Event, which set fire to telegraph stations worldwide in 1859. The Carrington Event was a geomagnetic storm caused by a coronal mass ejection (CME) that directly interacted with Earth's magnetic field. It didn't have as much effect on the Earth's atmosphere, especially compared to the ancient ESPE.

ESPEs, as their name suggests, are caused by a massive influx of particles from the Sun. These particles interact directly with the Earth's atmosphere, and, importantly for the purposes of dating, have a noticeable impact on Carbon-14 levels. Specifically, the amount of C-14, as it's commonly known in chemistry, is increased dramatically compared to a baseline. Since living things like trees sequester carbon, we can tell when events like this happen to measure the amount of C-14 embedded in those previously living things using a technique called radiocarbon dating.

Fraser talks through the Carrington event and how it impacts our engineering designs now.

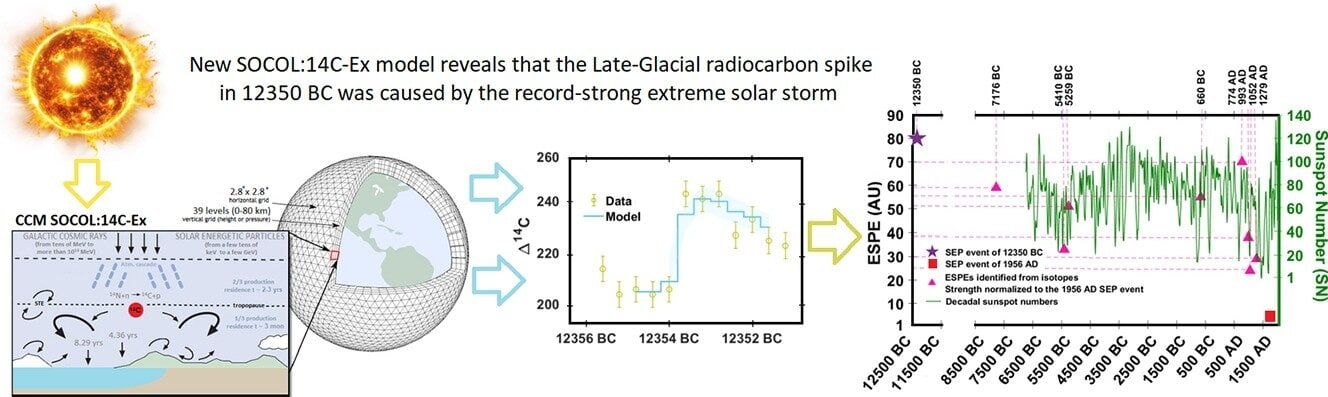

The paper does not describe new data—the tree rings they used to capture the 12350 BC event were found in southwestern Europe and described in a paper in 2023. The new work done in this paper was to apply a climatic model known as SOCOL:14C-Ex and use it to understand the impact the environment at the time had on the capture and sequestration of the C-14 isotopes from the ESPE.

When the ESPE hit, the Earth was in an entirely different geological age, known as the Late Glacial period, at the end of the last Ice Age, as compared to the Holocene period that has existed for the last 10,000 years. That means there were pretty massive geological differences that could play a role in how the C-14 was captured in the rings.

The Earth had weaker geomagnetic shielding in 12350 BC, allowing more particles to enter the atmosphere than a similarly-sized event would have in the modern day. However, it also had lower CO2 levels, meaning there was less Carbon-12 (a more stable isotope) to be transmuted into C-14. The climate itself was different, and while it could have impacted the C-14 levels by changing the efficacy of carbon sinks or increasing how the C-14 particles moved about the atmosphere, the study found that it had a relatively limited impact on the differences between modern-day and the carbon levels back then.

Solar storms can get pretty bad, as Fraser explains.

To prove what "modern day" would have been like, the researchers used one of eight other known extreme ESPEs found in other tree rings. This one occurred in 775 and was previously the most intense ESPE known to science. Plenty of other tree rings from Germany, New Zealand, Argentina, the US, and elsewhere already had known C-14 levels that could be used as a calibration, in this case, a proof of concept.

The researchers tested SOCOL:14C-Ex to estimate the storm's intensity in 775 and proved the model worked then. They then adjusted some of the parameters based on the above considerations to calculate the ESPE intensity in 12350 BC. They found that it was about 18% stronger than the event in 775, making it the strongest known ESPE yet found.

Understanding how the Sun's extremes can affect us will continue to play a central role as we move more and more of our infrastructure off-planet. Engineers will have to plan for these extremes, and knowing the limits will only help us understand what we need to design. And who knows, there may be even more extreme events in the fossil record that SOCOL:14C-Ex will eventually find.

Learn More:

K Golubenko et al -New SOCOL:14C-Ex model reveals that the Late-Glacial radiocarbon spike in 12350 BC was caused by the record-strong extreme solar storm

UT -It's Been a Year Since the Most Powerful Solar Storm in Decades. What Did We Learn?

UT -How Bad Can Solar Storms Get? Ask the Trees

UT -New Research Indicates the Sun may be More Prone to Flares Than we Thought

Universe Today

Universe Today