In the early 1960s, scientists developed the gravity-assist method, where a spacecraft would conduct a flyby of a major body in order to increase its speed. Many notable missions have used this technique, including the

Pioneer

,

Voyager,

Galileo, Cassini, and

New Horizons

missions. In the course of many of these flybys, scientists have noted an anomaly where the increase in the spacecraft's speed did not accord with orbital models.

This has come to be known as the "flyby anomaly", which has endured despite decades of study and resisted all previous attempts at explanation. To address this, a team of researchers from the

University Institute of Multidisciplinary Mathematics

at the Universitat Politecnica de Valencia have developed a new orbital model based on the maneuvers conducted by the

Juno

probe.

The study, which recently appeared online under the title "

A Possible Flyby Anomaly for Juno at Jupiter

", was conducted by Luis Acedo, Pedro Piqueras and Jose A. Morano. Together, they examined the possible causes of the so-called "flyby anomaly" using the perijove orbit of the

Juno

probe. Based on

Juno's

many pole-to-pole orbits, they not only determined that it too experienced an anomaly, but offered a possible explanation for this.

[caption id="attachment_61691" align="aligncenter" width="516"]

Artist's impression of the Pioneer 10 probe, launched in 1972 and now making its way out towards the star Aldebaran. Credit: NASA

[/caption]

To break it down, the speed of a spacecraft is determined by measuring the Doppler shift of radio signals from the spacecraft to the antennas on the

Deep Space Network

(DSN). During the 1970s when the

Pioneer 10* and 11*

probes were launched, visiting Jupiter and Saturn before heading off towards the edge of the Solar System, these probes both experienced something strange as they passed between 20 to 70 AU (Uranus to the Kuiper Belt) from the Sun.

Basically, the probes were both 386,000 km (240,000 mi) farther from where existing models predicted they would be. This came to be known as the "

Pioneer anomaly

", which became common lore within the space physics community. While the Pioneer anomaly was resolved, the same phenomena has occurred many times since then with subsequent missions. As Dr. Acebo told Universe Today via email:

"The “flyby anomaly” is a problem in astrodynamics discovered by a JPL’s team of researchers lead by John Anderson in the early 90s. When they tried to fit the whole trajectory of the Galileo spacecraft as it approached the Earth on December, 8th, 1990, they found that this only can be done by considering that the ingoing and outgoing pieces of the trajectory correspond to asymptotic velocities that differ in 3.92 mm/s from what is expected in theory. "The effect appears both in the Doppler data and in the ranging data, so it is not a consequence of the measurement technique. Later on, it has also been found in several flybys performed by Galileo again in 1992, the* NEAR [Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous mission] in 1998, Cassini in 1999 or Rosetta and Messenger in 2005. The largest discrepancy was found for the NEAR (around 13 mm/s) and this is attributed to the very close distance of 532 Km to the surface of the Earth at the perigee."*

[caption id="attachment_128262" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

NASA's Juno spacecraft launched on August 6, 2011 and should arrive at Jupiter on July 4, 2016. Credit: NASA / JPL

[/caption]

Another mystery is that while in some cases the anomaly was clear, in others it was on the threshold of detectability or simply absent - as was the case with

Juno

's flyby of Earth in October of 2013. The absence of any convincing explanation has led to a number of explanations, ranging from the influence or dark matter and tidal effects to extensions of General Relativity and the existence of new physics.

However, none of these have produced a substantive explanation that could account for flyby anomalies. To address this, Acedo and his colleagues sought to create a model that was optimized for the

Juno

mission while at perijove - i.e. the point in the probe's orbit where it is closest to Jupiter's center. As Acedo explained:

"After the arrival of Juno at Jupiter on July, 4th, 2016, we had the idea of developing our independent orbital model to compare with the fitted trajectories that were being calculated by the JPL team at NASA. After all, Juno is performing very close flybys of Jupiter because the altitude over the top clouds (around 4000 km) is a small fraction of the planet’s radius. So, we expected to find the anomaly here. This would be an interesting addition to our knowledge of this effect because it would prove that it is not only a particular problem with Earth flybys but that it is universal."

Their model took into account the tidal forces exerted by the Sun and by Jupiter's larger satellites - Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto - and also the contributions of the known zonal harmonics. They also accounted for Jupiter's multipolar fields, which are the result of the planet oblate shape, since these play a far more important role than tidal forces as

Juno

reaches perijove.

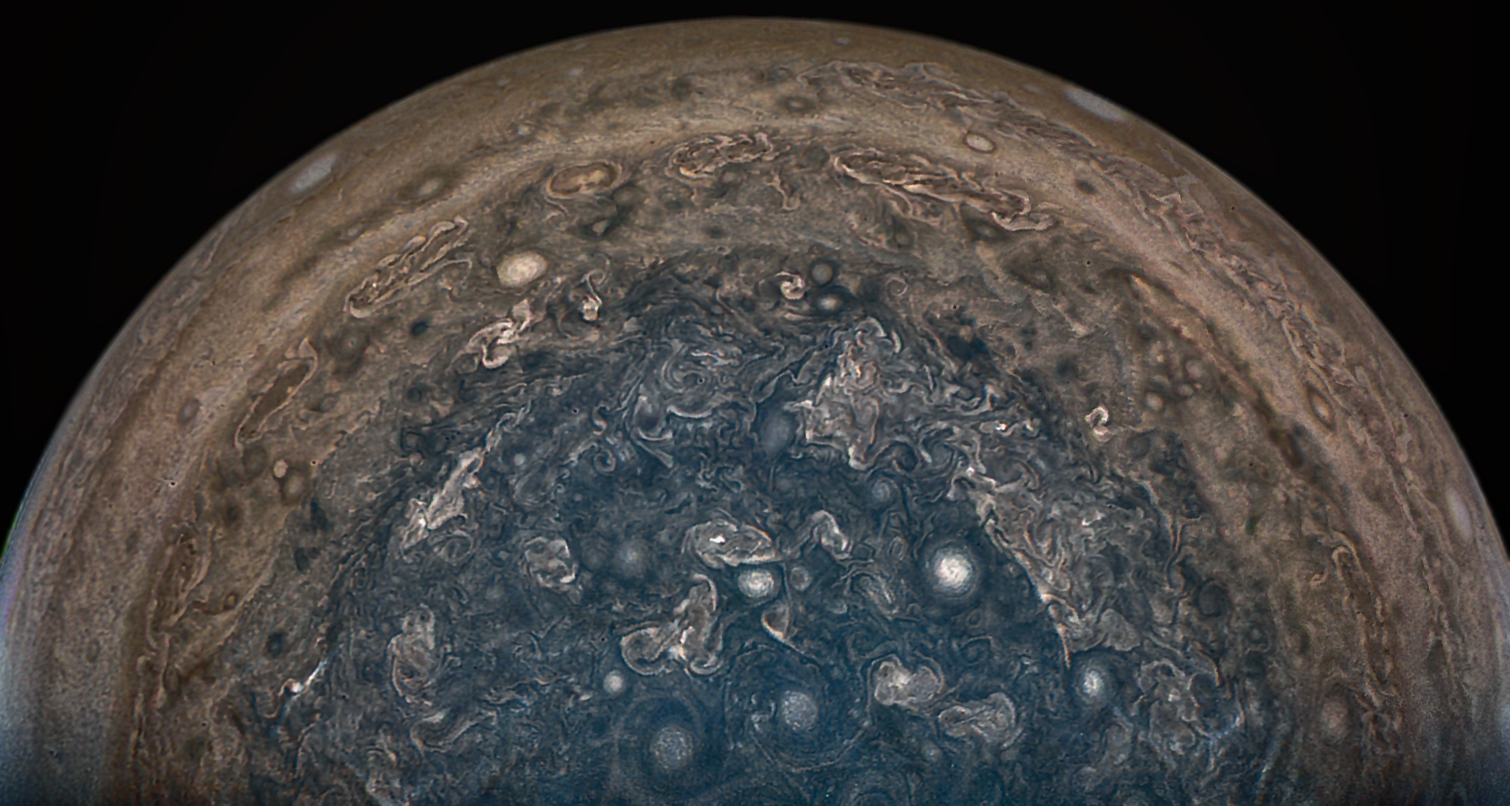

[caption id="attachment_129718" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Illustration of NASA's Juno spacecraft firing its main engine to slow down and go into orbit around Jupiter. Lockheed Martin built the Juno spacecraft for NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Credit: NASA/Lockheed Martin

[/caption]

In the end, they determined that an anomaly could also be present during the

Juno

flybys of Jupiter. They also noted a significant radial component in this anomaly, one which decayed the farther the probe got from the center of Jupiter. As Acebo explained:

"Our conclusion is that an anomalous acceleration is also acting upon the Juno spacecraft in the vicinity of the perijove (in this case, the asymptotic velocity is not a useful concept because the trajectory is closed). This acceleration is almost one hundred times larger than the typical anomalous accelerations responsible for the anomaly in the case of the Earth flybys. This was already expected in connection with Anderson et al.’s initial intuition that the effect increases with the angular rotational velocity of the planet (a period of 9.8 hours for Jupiter vs the 24 hours of the Earth), the radius of the planet and probably its mass."

They also determined that this anomaly appears to be dependent on the ratio between the spacecraft's radial velocity and the speed of light, and that this decreases very fast as the craft's altitude over Jupiter’s clouds changes. These issues were not predicted by General Relativity, so there is a chance that flyby anomalies are the result of novel gravitational phenomena - or perhaps, a more conventional effect that has been overlooked.

In the end, the model that resulted from their calculations accorded closely with telemetry data provided by the

Juno

mission, though questions remain.

"

Further research is necessary because the pattern of the anomaly seems very complex and a single orbit (or a sequence of similar orbits as in the case of Juno) cannot map the whole field," said Acebo. "A dedicated mission is

required but financial cuts and limited interest in experimental gravity may prevent us to see this mission in the near future."

It is a testament to the complexities of physics that even after sixty years of space exploration - and one hundred years since General Relativity was first proposed - that we are still refining our models. Perhaps someday we will find there are no mysteries left to solve, and the Universe will make perfect sense to us. What a terrible day that will be!

Further Reading: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics

Universe Today

Universe Today