The closest planet to the Sun is Mercury. It's a tiny world, even smaller than Saturn's moon Titan and Jupiter's moon Ganymede. That's unusual for a planetary system. Most star systems have a large world between the size of Earth and Neptune orbiting much closer than Mercury. A new study has figured out how these close-orbiting super-Earths form and clues about why they are so common.

When we started discovering exoplanets, it was generally thought that we mostly found large planets close to their star because they are the easiest to find. Most planets are discovered by the transit method, which favors larger planets with many transits in a short time. But as we found thousands of exoplanets, it became clear that it wasn't observation bias. Hot super-Earths are common in the galaxy.

This led to two main ideas as to their origin. The first is that the planets form farther away from their star but then migrate inward due to gravitational interactions from other protoplanets in the system. Computer simulations of our solar system suggest that gravitational interactions between Jupiter and Saturn caused the planets to shift orbits dramatically early on. In our case it drove the large planets farther away from the Sun. In other systems it could push worlds closer to their star. The other idea is that hot super-Earths form close to their star. This is what the new study suggests, but with an extra twist.

The team looked at a very young star known as V1298 Tau. It's only about 20 million years old but already has four planets orbiting it closer than Mercury orbits the Sun. Based on their transits, the planets have diameters 5 to 10 times that of Earth, which is the size range of Neptune to Jupiter. We've known about these planets for several years, but we've only known their sizes, not their masses. We had no idea whether they were dense worlds like Earth and Jupiter or less dense like Saturn.

In this new study, the team was able to determine the masses by looking at small timing shifts in the planetary transits. A single planet orbiting its star would follow a simple Keplerian orbit with transits happening with clockwork precision. But when there are multiple planets, the gravitational tugs between them mean that the orbits shift slightly and the transit times have small fluctuations. By modeling these fluctuations, the team was able to determine the masses of all four worlds. They found the masses ranged from 5 to 15 Earth masses, ranging from super-Earth to sub-Neptune.

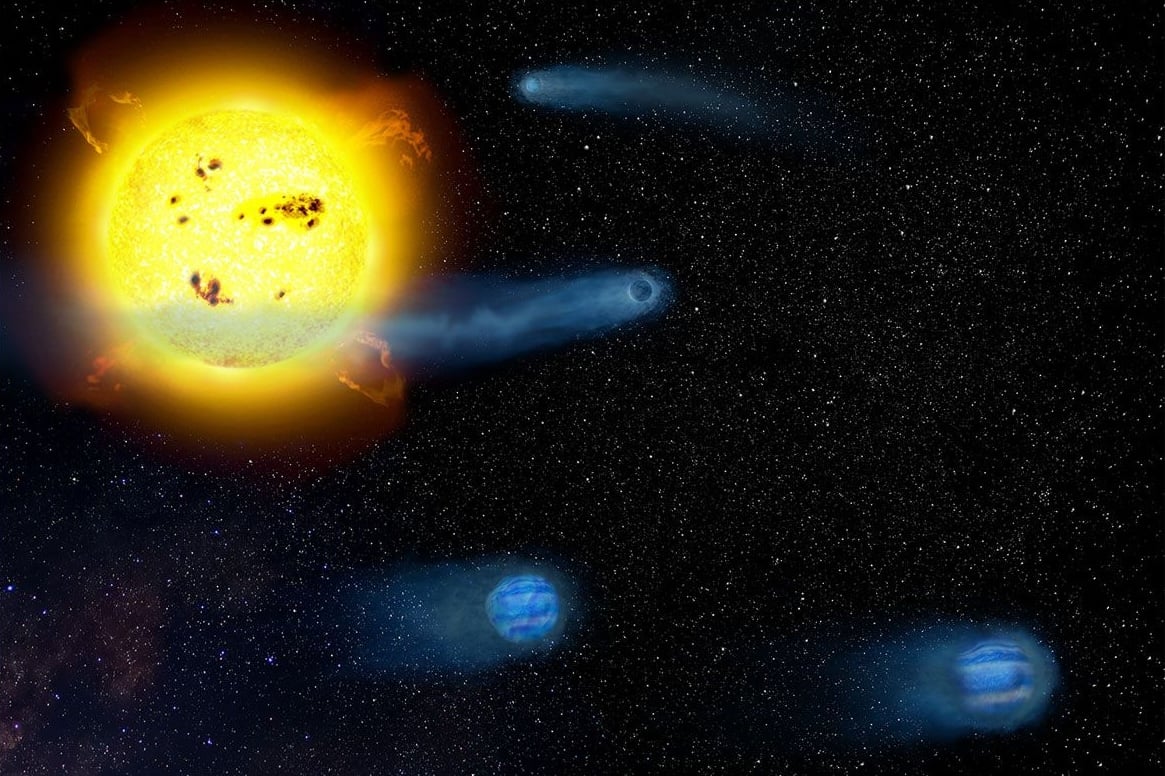

With the masses known, the team calculated the density of each planet and found they were all extremely low density. All four of the planets are super-puff worlds with average densities less than packing foam. This means they are planets with large, diffuse atmospheres of hydrogen and helium. Since young stars are notorious for flares and strong stellar winds, those atmospheres will be stripped from the planets over time. The team estimates that by the time the system matures, these planets will be whittled down to masses and densities similar to the hot super-Earths that are so common.

Gas giants form early in a star system. For close-orbiting planets, their star hammers away at them until they become smaller, denser worlds.

Reference: Livingston, John H., et al. "A young progenitor for the most common planetary systems in the Galaxy." Nature 649.8096 (2026): 310-314.

Universe Today

Universe Today