The JWST continues to live up to its promise by revealing things hidden from other telescopes. One of its lesser-known observations concerns Free-Floating Planets(FFP). FFPs have no gravitational tether to any star and are difficult to detect because they emit so little light. When the JWST detected 42 of them in the Orion Nebula Cluster, it gave astronomers an opportunity to study them more closely.

The FFPs in the Orion Nebula Cluster (ONC) are called Jupiter-Mass Binary Objects(JuMBOs). They range from 0.7 to 13 Jupiter masses, and their separations range from 28 to 384 astronomical units. These wide separations make them stand out from other populations of substellar binary objects, which have separations below 10 AU. Their existence at such wide separations poses a challenge to theories explaining how substellar and planetary-mass objects form.

Astronomers have conducted new research to examine how these objects can survive in dense star-forming regions. The study is titled "Can planet-planet binaries survive in star-forming regions?" and has been accepted for publication in the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The lead author is Richard Parker from the University of Sheffield.

Scientists have questions about JuMBOs' ability to survive in dense star-forming regions, and the ONC is the densest star-forming region within 500 parsecs of the Sun. The researchers point out that many studies report that stellar flybys disrupt both stellar and substellar binaries in regions like the ONC. The researchers wanted to determine if the 42 JuMBOs in the ONC represent only the survivors and if many more formed that didn't survive.

This artist's illustration shows a solitary free-floating planet adrift somewhere in the Milky Way. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (Caltech-IPAC)

This artist's illustration shows a solitary free-floating planet adrift somewhere in the Milky Way. Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (Caltech-IPAC)

"In this Letter, we investigate whether planet–planet binary systems can survive in dense star-forming regions, and what the implications of this are for the JuMBOs observed with JWST," the researchers explain. A key piece in this work is the extremely wide separations between the pairs. Such wide separations make them more susceptible to disruption, since their gravitational hold on each other is weakened by distance.

To find out, they ranN-body simulations showing the evolution of planet-planet binaries in star-forming regions. They used different values for the initial mass function, the separation distribution in planet-planet binaries, and the local stellar density.

"The relatively wide planet–planet binaries, and their relatively small binding energies, make them susceptible to disruption in all of our simulated star-forming regions," the authors write.

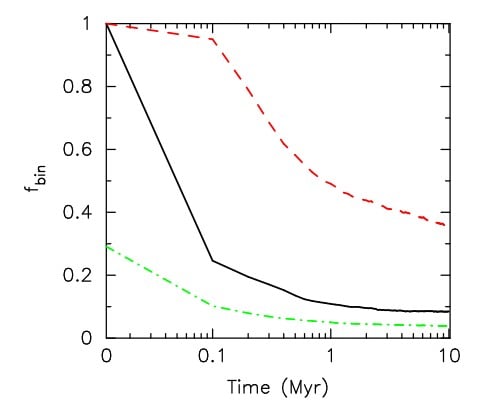

This figure from the research shows the simulation results. The lines are for objects below the hydrogen-burning mass limit, meaning no stellar-mass objects. The y-axis shows the initial binary fraction of low-mass objects. The solid black line shows how the binary fraction evolved in dense simulations. The red dashed line shows how the binary fraction evolved in lower-density simulations. The green dashed line shows how the binary fraction evolved in a simulation that included brown dwarfs, which drew their masses from the initial binary fraction. The planet-planet separations in all these simulations come from the JuMBOs in the ONC. Image Credit: Parker et al. 2025, MNRAS.

This figure from the research shows the simulation results. The lines are for objects below the hydrogen-burning mass limit, meaning no stellar-mass objects. The y-axis shows the initial binary fraction of low-mass objects. The solid black line shows how the binary fraction evolved in dense simulations. The red dashed line shows how the binary fraction evolved in lower-density simulations. The green dashed line shows how the binary fraction evolved in a simulation that included brown dwarfs, which drew their masses from the initial binary fraction. The planet-planet separations in all these simulations come from the JuMBOs in the ONC. Image Credit: Parker et al. 2025, MNRAS.

"It is clear from these simulations that a significant proportion of the observed JuMBOs would not survive in a star-forming region with densities commensurate with the majority of nearby star-forming regions," the authors explain. They also note that more widely separated systems are destroyed than closely separated systems, which is expected.

The results also show that the stellar density typical of many nearby star-forming regions would destroy many of the JuMBOs in the ONC regardless of their initial separation. "This implies that even more systems than the 42 reported in <Pearson & McCaughrean (2023)> would need to form, given the final binary fraction of 0.5 even in our lower-density simulations," the authors write.

In addition, the results also suggest that there may be even more wider JuMBOs than those observed in the ONC and that "... these wider systems would be even more susceptible to dynamical destruction than the observed systems."

That means that far more JuMBOs would have to have formed, and that's a challenge to our understanding of their formation mechanisms.

*Our current theories of planet formation cannot account for the existence of JuMBOs, especially at such wide separations. Artistic depiction of one of these systems, not to scale. Image Credit: Gemini Observatory/Jon Lomberg*

*Our current theories of planet formation cannot account for the existence of JuMBOs, especially at such wide separations. Artistic depiction of one of these systems, not to scale. Image Credit: Gemini Observatory/Jon Lomberg*

There are a handful of proposed formation mechanisms, and one or more of them could explain JuMBOs. They include disk fragmentation in protoplanetary disks, turbulent fragmentation in molecular clouds similar to how stars form, failed core accretion, dynamical capture, and binary star ejection. The problem with all of these mechanisms is that they have to explain not only formation but also the very wide separations in JuMBOs.

Whatever mechanisms are responsible, they have to be efficient. The research shows that while the JWST only detected 42 JuMBOs, many more must have formed before being disrupted.

As it stands now, none of them can.

Universe Today

Universe Today