When the

*Cassini spacecraft*

arrived around Saturn on July 1st, 2004, it became the fourth space probe to visit the system. But unlike the

*Pioneer 11*

and

*Voyager 1*

and

2

probes, the

Cassini

mission was the first to establish orbit around the planet for the sake of conducting long-term research. Since that time, the spacecraft and its accompanying probe - the

- have revealed a startling amount about this system.

On Friday, September 15th, the

Cassini

mission will official end as the spacecraft descends into Saturn's atmosphere. In part of this final maneuver,

Cassini

rec

ently

conducted one last distant

flyby of Titan

. This flyby is being referred to informally as "the goodbye kiss" by mission engineers, since it is providing the gravitational push necessary to send the spacecraft into Saturn's upper atmosphere, where it will burn up.

In the course of this flyby, the spacecraft made its closest approach to

Titan

on Tuesday, September 12th, at 12:04 p.m. PDT (3:04 p.m. EDT), passing within 119,049 kilometers (73,974 mi) of the moon's surface. The maneuver was designed to slow the probe down and lower the altitude of its orbit around the planet, which will cause it to descend into Saturn's atmosphere in a few day's time.

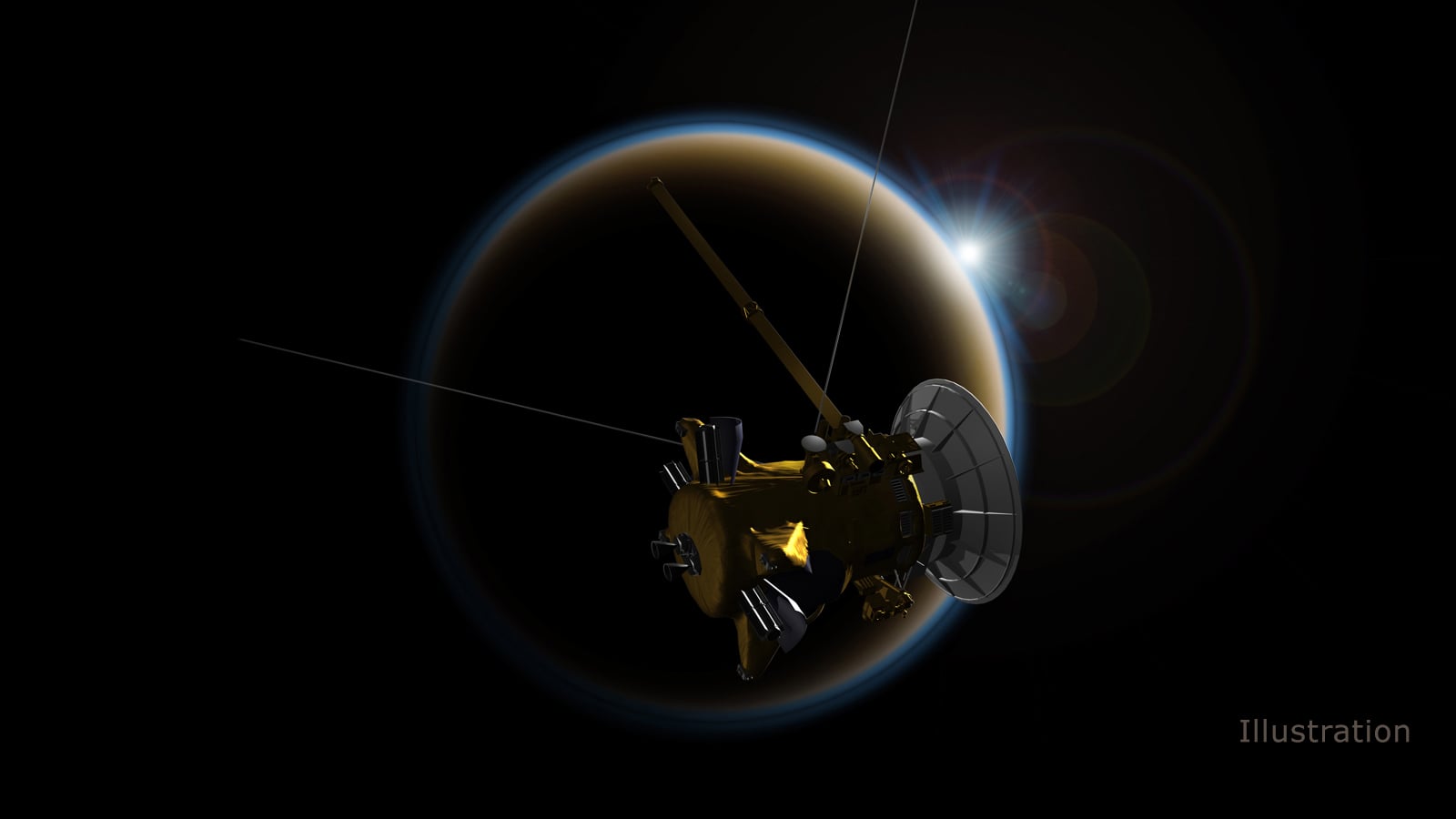

[caption id="attachment_112895" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Artist's conception of Cassini winging by Saturn's moon Titan (right) with the planet in the background. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

[/caption]

The flyby also served as an opportunity to collect some final pictures and data on Saturn's largest moon, which has been a major focal point for much of the

Cassini-Huygens

mission. These will all be transmitted back to Earth at 18:19 PDT (21:19 EDT) when the spacecraft makes contact, and navigators will use this opportunity to confirm that

Cassini

is on course for its final dive.

All told, the spacecraft made hundreds of passes over Titan during its 13-year mission. These included a total of 127 precisely targeted encounters at close and far range (like this latest flyby). As

Cassini

Project Manager Earl Maize, from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said in a NASA

press statement

:

In the course of making its many flybys, the

Cassini

spacecraft revealed a great deal about the composition of Titan's atmosphere, its

methane cycle

(similar to Earth's hydrological cycle) and the kinds of weather it experiences in its polar regions. The probe also provided high-resolution radar images of Titan's surface, which included topography and images of its northern

methane lakes

.

[caption id="attachment_122671" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Artist depiction of Huygens lander touching down on the surface of Saturn's largest moon Titan. Credit: ESA

[/caption]

Cassini's

first flyby of Titan took place on July 2nd, 2004 - a day after the spacecraft's orbital insertion - where it approached to within 339,000 km (211,000 mi) of the moon's surface. On December 25th, 2004,

Cassini

released the

Huygens lander

into the planet's atmosphere. The probe touched down on January 14th, 2005, taking hundreds of pictures of the moon's surface in the process.

In

November of 2016

, the spacecraft began the

Grand Finale

phase of its mission

,

where it would make 22 orbits between Saturn and its rings. This phase began with a flyby of Titan that took it to the gateway of Saturn's' F-ring, the outermost and perhaps most active ring around Saturn. This was followed by a final close flyby of Titan on

April 22nd, 2017

, taking it to within 979 km (608 mi) of the moon's surface.

Throughout its mission,

Cassini

also revealed some significant things about Saturn's atmosphere, its hexagonal storms, its ring system, and its extensive system of moons. It even revealed previously-undiscovered moons, such as

Methone

,

Pallene

and

Polydeuces

. Last, but certainly not least, it conducted studies of Saturn's moon

Enceladus

that revealed evidence of a interior ocean and plume activity around its southern polar region.

These discoveries are part of the reason why the probe will end its mission by plunging into Saturn's atmosphere, about

two days and 16 hours

from now. This will cause the probe to burn up, thus preventing contamination of moons like Titan and Enceladus, where microbial life could possibly exist. Finding evidence of this life will be the main focus of future missions to the Saturn system, which are likely to launch in the next decade.

So long and best wishes,

Cassini!

You taught so much in the past decade and we hope to follow up on it very soon. We'll all miss you when you go!

Further Reading: NASA

Universe Today

Universe Today