This past Monday (June 27th), the

National Astronomy Meeting

- which is hosted by the Royal Astronomy Society - kicked off at the University of Nottingham in the UK. As one of the largest professional conferences in Europe (with over 500 scientists in attendance), this annual meeting is an opportunity for astronomers and scientists from a variety of fields to present that latest in their research.

And of the many presentations made so far, one of the most exciting came from a research team from the University of Nottingham's School of Physics and Astronomy, which presented the latest near-infrared images obtained by the

Ultra Deep Survey

(UDS). In addition to being a spectacular series of pictures, they also happened to be the deepest view of the Universe to date.

The UDS survey, which began in 2005, is one of the five projects that make up the

UKIRT's Infrared Deep Sky Survey

(UKIDSS). For the sake of their survey, the UDS team relies on the Wide Field Camera (WFCAM) on the

United Kingdom Infrared Telescope

in Mauna Kea, Hawaii. At 3.8-metres in diameter, the UKIRT is the world's second largest telescope dedicated to infrared astronomy.

As Professor Omar Almaini, the head of the University of Nottingham research team, explained to Universe Today via email:

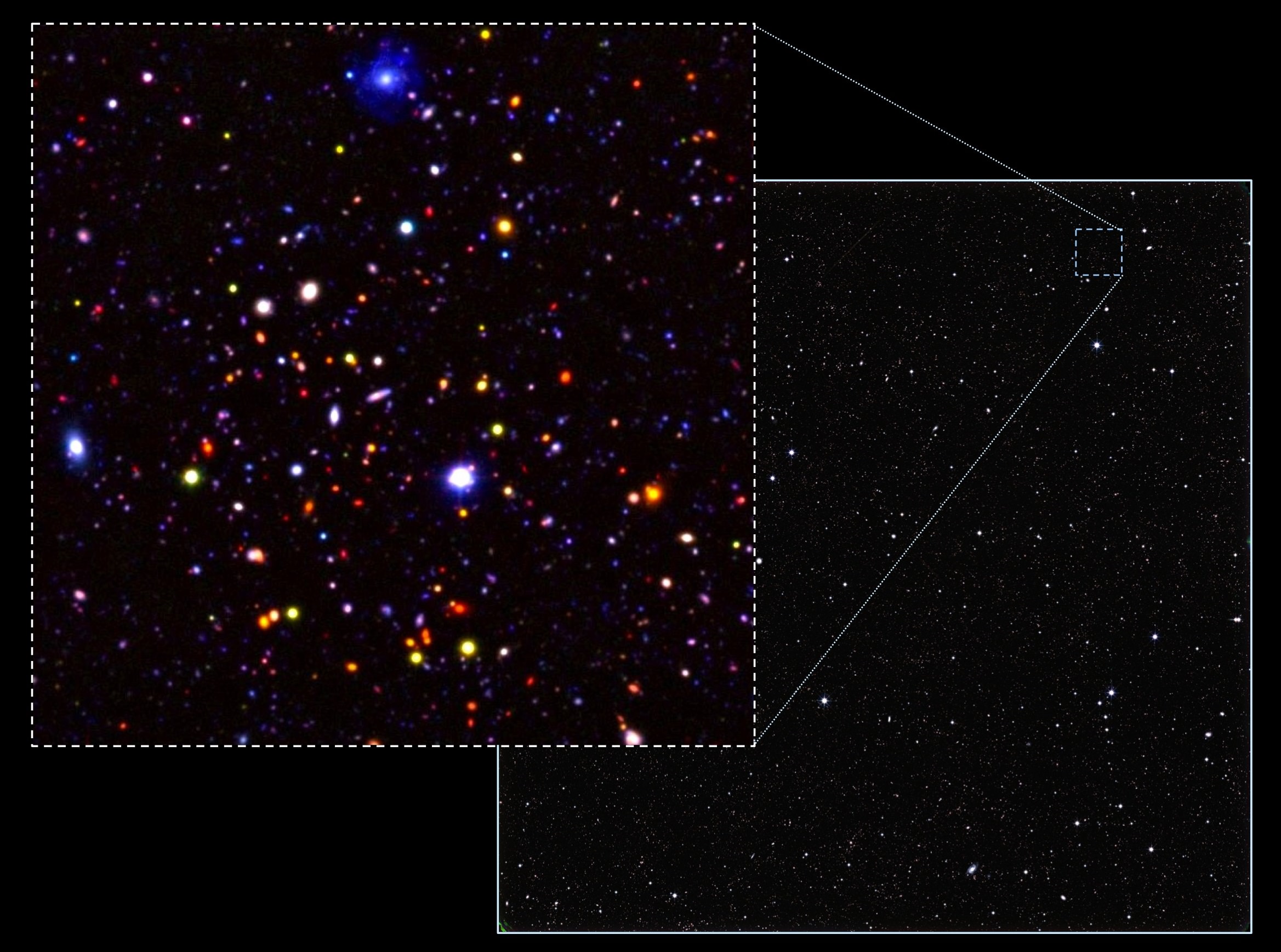

[caption id="attachment_129658" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

An optical/IR image taken with the United Kingdom Infrared Telescope as part of the UDS. Credit: nottingham.ac.uk

[/caption]

Ultimately, the goal of UDS is shed light on how and when galaxies form, and to chart their evolution over the course of the last 13 billion years (roughly 820 million years after the Big Bang). For over a decade, the UDS has been observing the same patch of sky repeatedly, relying on optical and infrared imaging to ensure that the light of distant objects (which is redshifted due to the profound distances involved) can be captured.

"Stars emit most of their radiation at optical wavelengths, which is redshifted to the near-infrared at high redshift," said Almaini. "Near-infrared surveys therefore provide the least biased census of galaxies in the early Universe and the best measurements of the stellar mass. Deep optical surveys will only detect galaxies that are bright in the rest-frame ultraviolet, so they are biased against galaxies that are obscured by dust, or those that have stopped forming stars."

In total, the project has accumulated more than 1000 hours of exposure time, detecting over two hundred and fifty thousand galaxies - several hundred of which were observed within the first billion years after the Big Bang. The final images, which were released yesterday and presented at the National Astronomy Meeting, showed an area four times the size of the full Moon, and at an unprecedented depth.

Data previously released by the UDS project has already led to several scientific advances. These include studies of the earliest galaxies in the Universe after the Big Bang, measurements on the build-up of galaxies over time, and studies of the large-scale distribution of galaxies to measure the influence of dark matter.

[caption id="attachment_116316" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Research into the USD images is inspiring scientific research, which includes studies into dark matter. Credit: Max-Planck Institute for Astrophysics

[/caption]

With this latest release, many more are anticipated, with astronomers around the world spending the next few years studying the early stages of galaxy formation and evolution. As Almaini put it:

Along with the subject of galaxy surveys and large scale structure, "galaxy formation and evolution" and "galaxy surveys and large scale structure" were two of the 2016 National Astronomy Meeting's main themes. Naturally, the UDS release fit neatly into both categories. The others themes included the Sun, stars and planetary science, gravitational waves, modified gravity, archeoastronomy, astrochemistry, and education and outreach.

The Meeting will run until tomorrow (Friday, July 1st), and also included a presentations on the latest

infrared images of Jupiter

, which were taken by the ESO in preparation for the

Juno

spacecraft's arrival on July 4th.

Further Reading: Royal Astronomical Society

Universe Today

Universe Today