It's a well-known fact that Supermassive Black Holes (SMBH) play a vital role in the evolution of galaxies. Their powerful gravity and the way it accelerates matter in its vicinity causes so much radiation to be released from the core region - aka. an Active Galactic Nucleus (AGN) - that it will periodically outshine all the stars in the disk combined. In addition, some SMBHs accelerate infalling dust and gas into jets that emanate from the poles, sending streams of super-heated material millions of light-years at close to the speed of light.

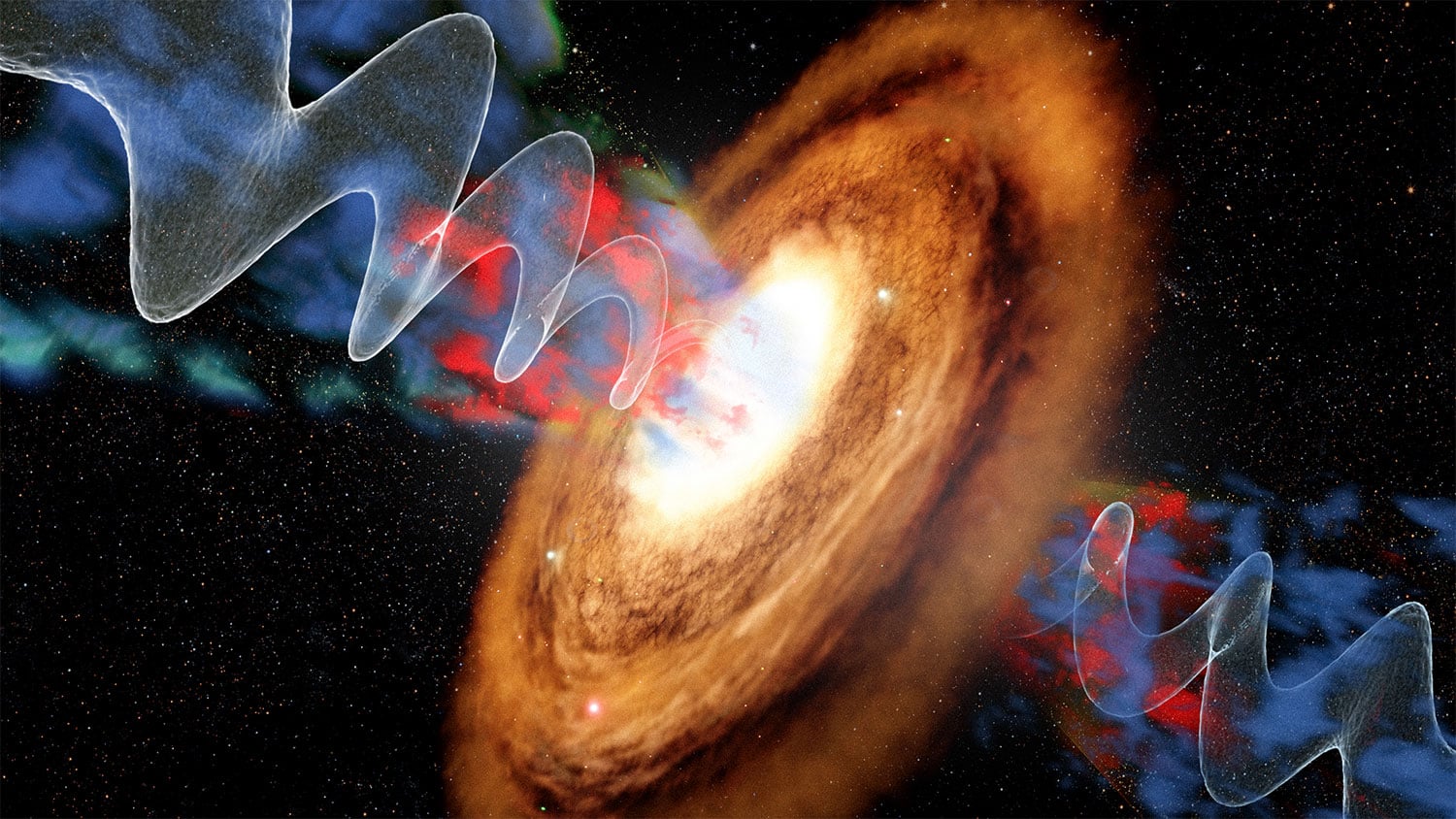

Since the first of these "relativistic jets" was observed, scientists have been eager to learn more about them and their role in galaxy evolution. In a surprising first, a team of astronomers led by researchers at the University of California, Irvine (UC Irvine) and the Caltech Infrared Processing and Analysis Center (IPAC) recently uncovered the largest and most extended jet ever observed in a nearby galaxy. Their observations also revealed vast "wobbly" structures, the clearest evidence to date that SMBHs can dramatically reshape their host galaxies far beyond their cores.

Their findings, published in the journal Science, were also the subject of a presentation made at the 247th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Phoenix, Arizona. The team observed the galaxy VV340a using the W. M. Keck Observatory on Maunakea, Hawaiʻi, and identified a jet extending up to 20,000 light-years from its center. Thanks to the Keck Cosmic Web Imager (KCWI) on the Observatory’s Keck II telescope, they discerned a spear-like structure aligned with the galactic nucleus.

The data obtained from KCWI allowed the team to model the amount of material being expelled and determine whether the outflow could be affecting the galaxy’s evolution. Said Justin Kader, a UC Irvine postdoctoral researcher and the lead author on the study, in a W.M. Keck Observatory press release:

The Keck Observatory data is what allowed us to understand the true scale of this phenomenon. The gas we see with Keck Observatory reaches the farthest distances from the black hole, which means it also traces the longest timescales. Without these observations, we wouldn’t know how powerful — or how persistent — this outflow really is.

The team combined the Keck data with infrared observations made with the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and radio images from the Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA). While Webb's infrared data revealed the energetic heart of the galaxy, Keck's optical data showed how that energy propagates outward. The VLA radio data, meanwhile, revealed a pair of plasma jets twisted into a helical pattern as they move outward. The combined data presented a compelling picture, with a few surprises along the way.

For instance, the Webb data identified intensely energized “coronal” gas, the superheated plasma erupting from either side of the black hole, measuring several thousand parsecs across. Most observed coronae measure in the hundreds of parsecs, making this the most extended coronal gas structure ever observed. Meanwhile, the VLA radio data revealed a pair of plasma jets twisted into a helical pattern as they moved outward, evidence of a rare phenomenon in which a jet's direction slowly wobbles over time (known as jet precession).

In addition, the KCWI data showed that the jet arrests star formation by stripping the galaxy of gas at a rate of about 20 Solar masses a year. But what was most surprising was the fact that these jets were observed in a relatively young galaxy like VV340a, which is still in the early stages of a galactic merger. Typically, such jets are observed in older elliptical galaxies that have long since ceased star formation. This discovery challenges established theories of how galaxies and their SMBHs co-evolve and could provide new insights into how the Milky Way came to be. Said Kader:

This is the first time we’ve seen a precessing, kiloparsec-scale radio jet driving such a massive outflow in a disk galaxy. There’s no clear fossil record of something like this happening in our galaxy, but this discovery suggests we can’t rule it out. It changes the way we think about the galaxy we live in.

The next step for the team will involve higher-resolution radio observations to determine whether a second SMBH could be at the center of VV340a, which could be causing the jets' wobble. “We’re only beginning to understand how common this kind of activity may be,” said Vivian U, an associate scientist at Caltech/IPAC and the second and senior author of the study. “With Keck Observatory and these other powerful observatories working together, we’re opening a new window into how galaxies change over time.”

Further Reading: W.M. Keck Observatory

Universe Today

Universe Today