Gravitational Lensing is a vital tool for astronomers to observe objects that are too distant or faint (or both) to be resolved by current instruments. This method leverages a prediction from Einstein's Theory of General Relativity, namely that massive objects alter the curvature of spacetime. When a "lens" comes into view, its gravitational field bends and amplifies light from more distant objects. In a recent study, a team of astronomers used a combination of ground-based telescopes to discover the first spatially resolved, gravitationally lensed supernova.

Located 10 billion light-years from Earth, this object SN 2025wny went supernova when the Universe was just 4 billion years old. Ordinarily, a supernova at this distance would be too faint for ground-based observatories, but the presence of two gravitational lenses boosted its brightness exponentially. Observing this recently exploded (superluminal) object provides astronomers with a rare look at a supernova that occurred in the early Universe. The discovery also provides additional confirmation for General Relativity, which has been confirmed in the most extreme scenarios.

The research was led by Joel Johansson, a researcher from the Oskar Klein Centre at Stockholm University (OKC-SU). He was joined by colleagues from the OKC-SU, the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), the Center for Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA), the DIRAC Institute, the Institute of Gravitational Wave Astronomy, the Excellence Cluster ORIGINS center, the McWilliams Center for Cosmology and Astrophysics, the NSF-Simons AI Institute for the Sky (SkAI), and multiple universities.

The discovery relied on cutting-edge observations made by multiple telescopes. This included the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF) at the Palomar Observatory in California, which first detected the explosion while monitoring the night sky. The Nordic Optical Telescope (NOT) at the La Palma Observatory provided early spectroscopy of the transient, while the Liverpool Telescope (LT) provided four separate images of SN 2025wny. Finally, the Keck Observatory provided the spectra that confirmed SN 2025wny's classification (Type Ia) extreme distance.

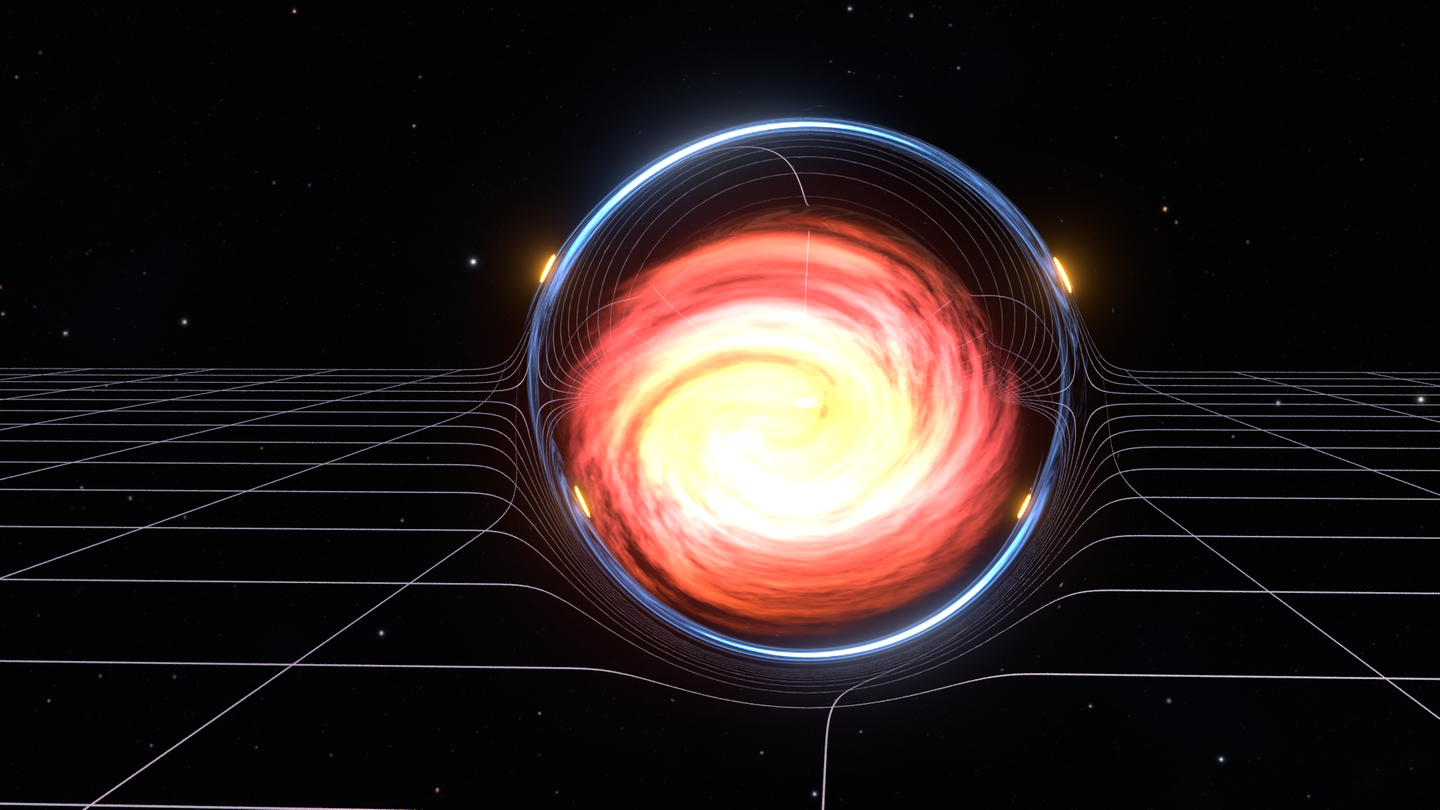

As the authors note, the presence of two foreground galaxies in this study boosted the supernova's brightness by a factor of 50 and split it into spatially-seperated images. This is a common phenomenon with gravitational lensing, where the curvature of spacetime around the "lens" causes light to be distributed in different patterns, depending on the alignment. When the lens and object are perfectly aligned, an "Einstein Ring" results, while other alignments can lead to up to four distinct images known as an "Einstein Cross."

"This is nature’s own telescope," said Johansson in a Stockholm University press release. "The magnification lets us study a supernova at a distance where detailed observations would otherwise be impossible." In addition to studying distant objects, scientists use gravitational lenses to probe the unresolved mysteries of the cosmos. This includes measuring the distribution of Dark Matter, the mysterious invisible matter that constitutes 85% of the Universe's mass, and the equally mysterious Hubble Constant.

Named in honor of Edwin Hubble, who confirmed that the Universe was in a state of expansion in 1929, the Hubble Constant is the measured rate at which it is expanding. For decades, scientists have worked to constrain the Constant by measuring cosmic distances over different scales. For this, they rely on different methods depending on the distances involved, collectively known as the Cosmic Distance Ladder. The only problem is that, depending on the method, the measured rate of expansion differs - i.e., they are in "tension" with each other.

With spatially-seperated images, the light takes different paths around the intervening galaxy and arrives at different times. Measuring these delays provides astronomers with an independent way to determine the Hubble Constant. "A lensed supernova with multiple, well-resolved images provides one of the cleanest ways to measure the expansion rate of the Universe," said co-author Ariel Goobar, also a researcher with the OKC-SU. "SN 2025wny is an important step toward resolving one of cosmology’s most significant challenges."

Using Keck's Low Resolution Imaging Spectrometer (LRIS), the team examined each supernova image and the lensing galaxies. The resulting spectra revealed the presence of chemical elements (carbon, iron, and silicon), which provided accurate estimates of its redshift and nature. "The spectrum taken with LRIS provides the most convincing measurement of its distance/redshift and pinpointed its classification as a superluminous supernova, which is a rare subclass," said Caltech researcher Yu-Jing Qin, who led the LRIS observations. "We were really impressed by the data quality and are pursuing further observations using other Keck instruments."

The discovery of SN 2025wny demonstrates that strongly lensed supernovae at considerable distances can be observed with today’s instruments. This provides a crucial proof of concept for the Vera C. Rubin Observatory’s planned Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), which is expected to discover hundreds of supernovae. Follow-up observations are already planned using Hubble and Webb to study the images further, measure time delays with greater precision, and refine the gravitational lens model.

Further Reading: W.M. Keck Observatory, arXiv

Universe Today

Universe Today