Next week, asteroid researchers and spacecraft engineers from all around the world will gather in Rome to discuss the latest in asteroid defense. The three-day International AIDA Workshop, which will run from Sept. 11th to 13th, will focus on the development of the joint NASA-ESA Asteroid Impact Deflection Assessment (AIDA) mission.

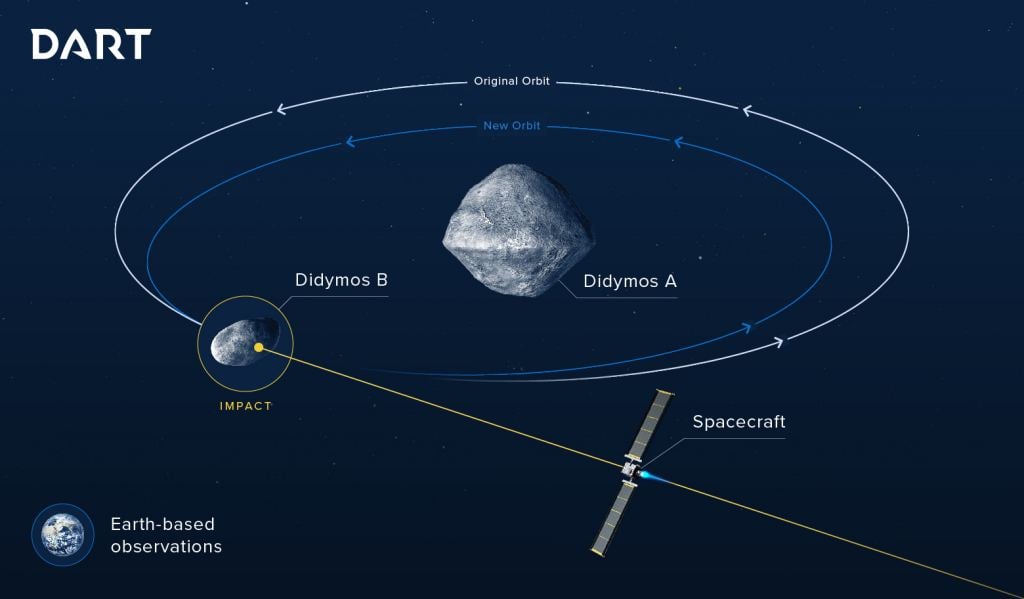

The purpose of this two-spacecraft system is to deflect the orbit of one of the bodies that make up the binary asteroid Didymos, which orbits between Earth and Mars. While one spacecraft will collide with a binary Near-Earth Asteroid (NEA), the other will observe the impact and survey the crash site in order to gather as much data as possible about this method of asteroid defense.

The target for this joint mission is Didymos, a near-Earth binary asteroid system that consists of a larger asteroid and an orbiting "moonlet". The main body of this system measures about 780 meters (2,560 ft) in diameter while its moonlet measures about 160 m (525 ft) in diameter. It was selected as part of a careful decision process that sought a deflection target that could provide a maximum scientific return.

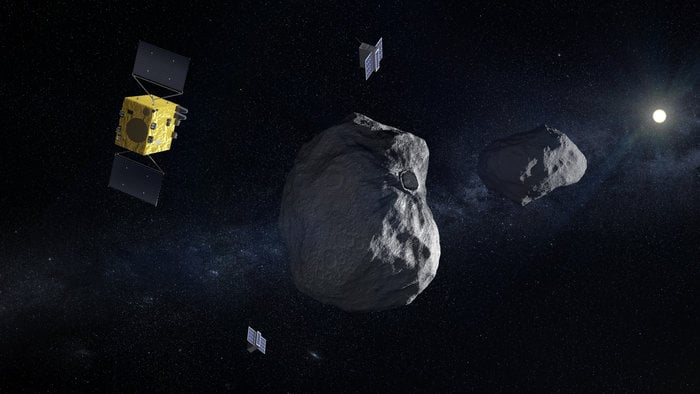

NASA's contribution to AIDA is known as the Double Asteroid Impact Test (DART) spacecraft, which is currently under construction. The Italian-made miniature CubeSat known as the Light Italian CubeSat for Imaging of Asteroids (LICIA) will be accompanying DART and deploying simultaneously to record the moment of impact.

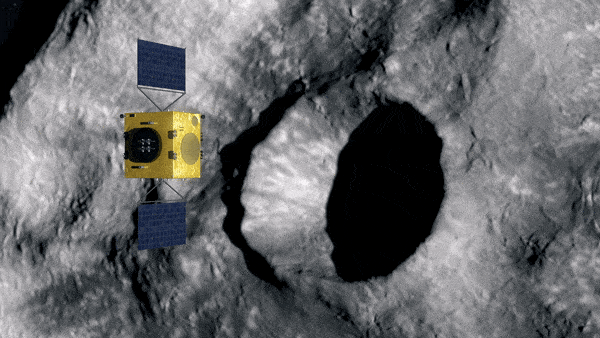

Then there's the ESA's Hera, which will perform a close-up survey of the asteroid after the DART spacecraft impacts on the surface. This will consist of taking measurements of the asteroid's mass and a detailed assessment of the impact crater's shape. Hera will also deploy two CubeSats to conduct close-up surveys and the first-ever radar probe of an asteroid close-up.

DART is currently being constructed at the John Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL), with support being provided by multiple NASA centers and the Planetary Defense Coordination Office (PDCO). The spacecraft is scheduled to launch sometime in the Summer of 2021 and will collide with Didymos' moonlet by September of 2002 - while traveling at a velocity of 6.6 km/s (23,760 km/h; 14,764 mph).

Meanwhile, Hera is currently in the final stretch of its B2 phase design work ahead of the Space19+ Ministerial Conference this November. It is here that Europe's space ministers will decide whether or not to deploy the spacecraft, which will launch in October of 2024 and reach Didymos by 2026 (if the ministers decide that the mission is a go).

However, there seems little reason to doubt that Space 19+ (which is part of the proposed ESA Space Safety Programme) will decide to send Hera to Didymos to evaluate the effectiveness of asteroid deflection. As Ian Carnelli, manager of the Hera mission for the ESA, explained:

"DART can perform its mission without Hera – the effect of its impact on the asteroid’s orbit will be measurable using Earth ground-based observatories alone. But flying the two missions together will greatly magnify their overall knowledge return.Hera will* in fact gather essential data to turn this one-off experiment into an asteroid deflection technique applicable to other asteroids.* "

Hera will also be the first ESA mission to rendezvous with a binary asteroid system, which are believed to make up around 15% of all known asteroids and are still something of a mystery to astronomers. The spacecraft will also test a variety of important new technologies, which include deep- space CubeSats, inter-satellite links and autonomous image-based navigation techniques.

Lastly, the joint NASA/ESA AIDA mission will serve as an opportunity to conduct operations in a low gravity environment. This will provide essential data that will prove very handy when it comes time to mount future missions to Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs), the Moon, and Mars.

"I also believe it is vital that Europe plays a leading role in AIDA, an innovative mission originally developed through ESA research back in 2003," added Carnelli. "An international effort is the appropriate way forward – planetary defense is in everyone's interest."

The results returned by Hera, DART, and the other elements of the AIDA mission will greatly inform the efforts of scientists that are committed to developing defenses against asteroids. In addition to aforementioned benefits, they will allow researchers to better model the efficiency of collisions.

This is key to making the leap from this experiment to a well-honed technique that could be a major part of planetary defense someday.

*Further Reading: ESA*

Universe Today

Universe Today