There wasn’t a lot of elbow room when six people from the Endeavour shuttle floated into the baby International Space Station on Dec. 10, 1998, but the cramped quarters resonated with possibility in STS-88 commander Bob Cabana’s mind.

“It’s hard to believe 15 years ago we put those first modules together, and we have this facility today that’s the size of a football field,” said Cabana in an interview today (Nov. 20) with Universe Today.

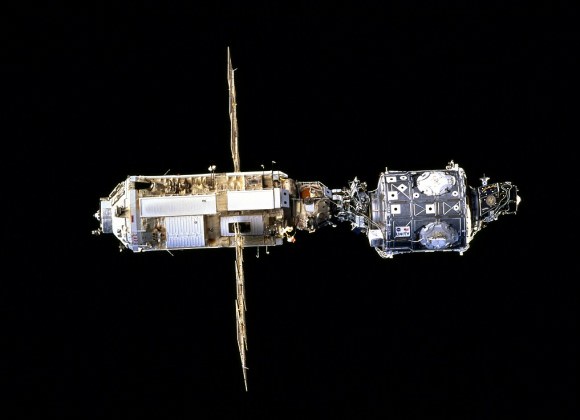

Cabana, who is now the director of the Kennedy Space Center, oversaw a complex mission that included joining the Russian Zarya and U.S. Unity modules, three spacewalks to get the modules powered and ready for humans to enter, and the pressure of public relations activities surrounding the opening of the station itself.

“That was a very special day, when we went into Unity and Zarya for the first time. There was a lot of excitement and anticipation,” Cabana said. He and Russian Sergei Krikalev — who would go on to become the person who spent the most time in space, at 803 days — entered the tiny hatches side by side to emphasize the international participation.

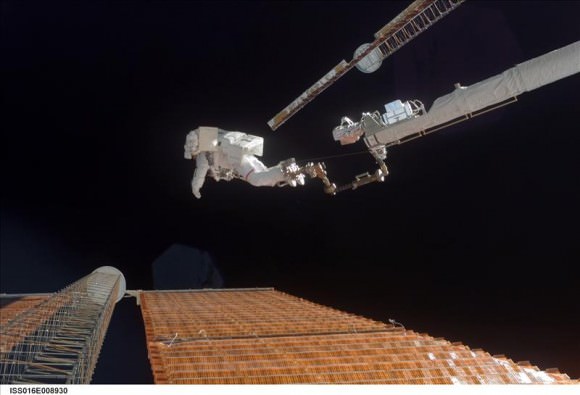

As is typical of spaceflight, the astronauts spent most of their day at work, busily waking up the station and testing its systems. NASA astronauts Jerry Ross and James Newman put together a communications system. Other crew members tested the videoconference equipment — important for press conferences as well as talking to scientists on the ground. Equipment and supplies in Zarya had to be unstowed and organized.

There also was the first repair on station, when Krikalev and NASA astronaut Nancy Currie replaced a faulty unit in Zarya “which controlled the discharging of stored energy from one of the module’s six batteries,” NASA wrote in an update at the time.

Cabana wanted his crew to get eight hours of sleep, but the excitement of that first day kept everybody up until 2:30 in the morning despite the wakeup call coming at 7 a.m.

“We were talking about what the ISS means, what will be accomplished with this cornerstone,” Cabana recalled, and said he is pleased with what has come to pass in the next 15 years. “It had come true. Everything we thought that could be has come together. That was a very special night, thinking about the future and how important the International Space Station was.”

The heaviest construction finished in 2011, and larger crews of six were allowed on board rather than the beginning crews of just three. NASA is now trying to position the station as a venue for microgravity science to justify the expense of running it. The astronauts, however, must balance their time doing science with the normal chores and maintenance the station requires. (The recent Expedition 35/36 missions were extremely productive in terms of science return, NASA astronaut Chris Cassidy told Universe Today in a past interview.)

All buildings on Earth require upgrades from time to time to stay safe and up to date, and the ISS is no different. Cabana said analysis will be done to “extend the life on some of the modules, but we don’t see that as a large issue.” The reason? The crews do “an outstanding job” keeping the station humming along with routine maintenance, he said.

Today (Nov. 20) marks the 15th anniversary of Zarya’s launch into orbit. The station partners are currently committed until 2020, meaning negotiations are forthcoming to see what to do with the station in the years afterwards. It’s unclear what will happen next — the recession is still reverberating in the United States and overseas — but today, the agencies focused on the successes.

Each partner agency tweeted facts and science concerning the ISS under the hashtag #ISS15, and invited people using all forms of social media to share their thoughts on the station. What are some notable things about the station, and what is a good use of it in the future, in your opinion? Let us know in the comments.