Hey, remember Comet C/2012 S1 ISON? Who can forget the roller-coaster ride that the touted “Comet of the Century” took us on last year. Well, ISON could have one more trick up its cosmic sleeve –although it’s a big maybe — in the form of a meteor shower or (more likely) a brief uptick in meteor activity this week.

In case you skipped 2012 and 2013, or you’re a time traveler who missed their temporal mark, we’ll fill you in on the story thus far.

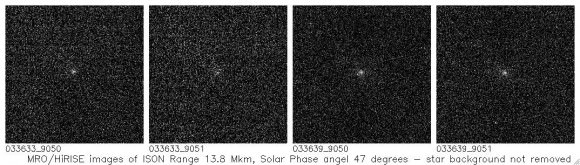

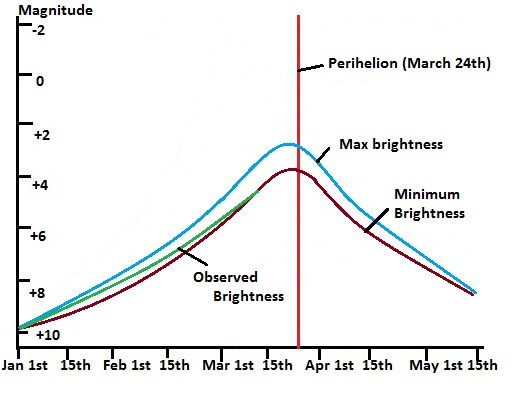

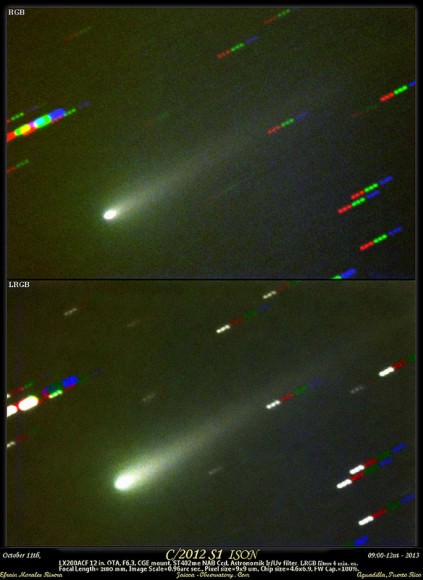

Comet ISON was discovered by Artyom Novichonok and Vitali Nevski on September 21st, 2012 as part of the ongoing International Scientific Optical Network (ISON) survey. Shortly after its discovery, researchers knew they had spotted something special: a sungrazing comet already active at over 6.4 Astronomical Units (A.U.s) from the Sun. The Internet then did what it does best, and promptly ran with the story. There were no shortage of Comet ISON conspiracy theories for science writers to combat in 2013. It’s still amusing to this day to see predictions for comet ISON post-perihelion echo through calendars, almanacs and magazines compiled and sent to press before its demise.

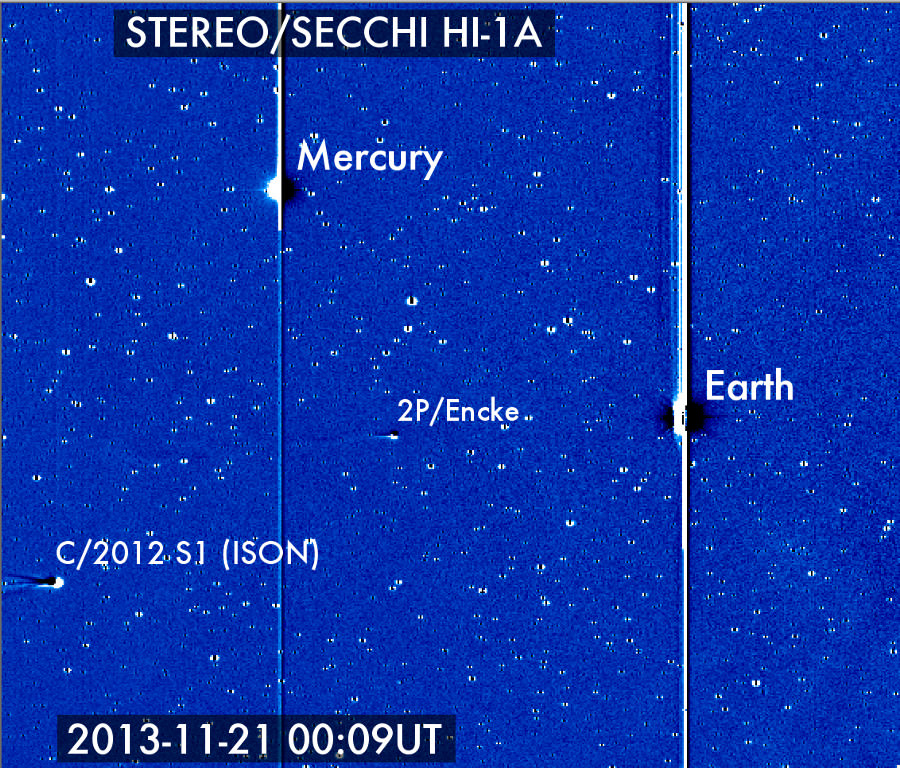

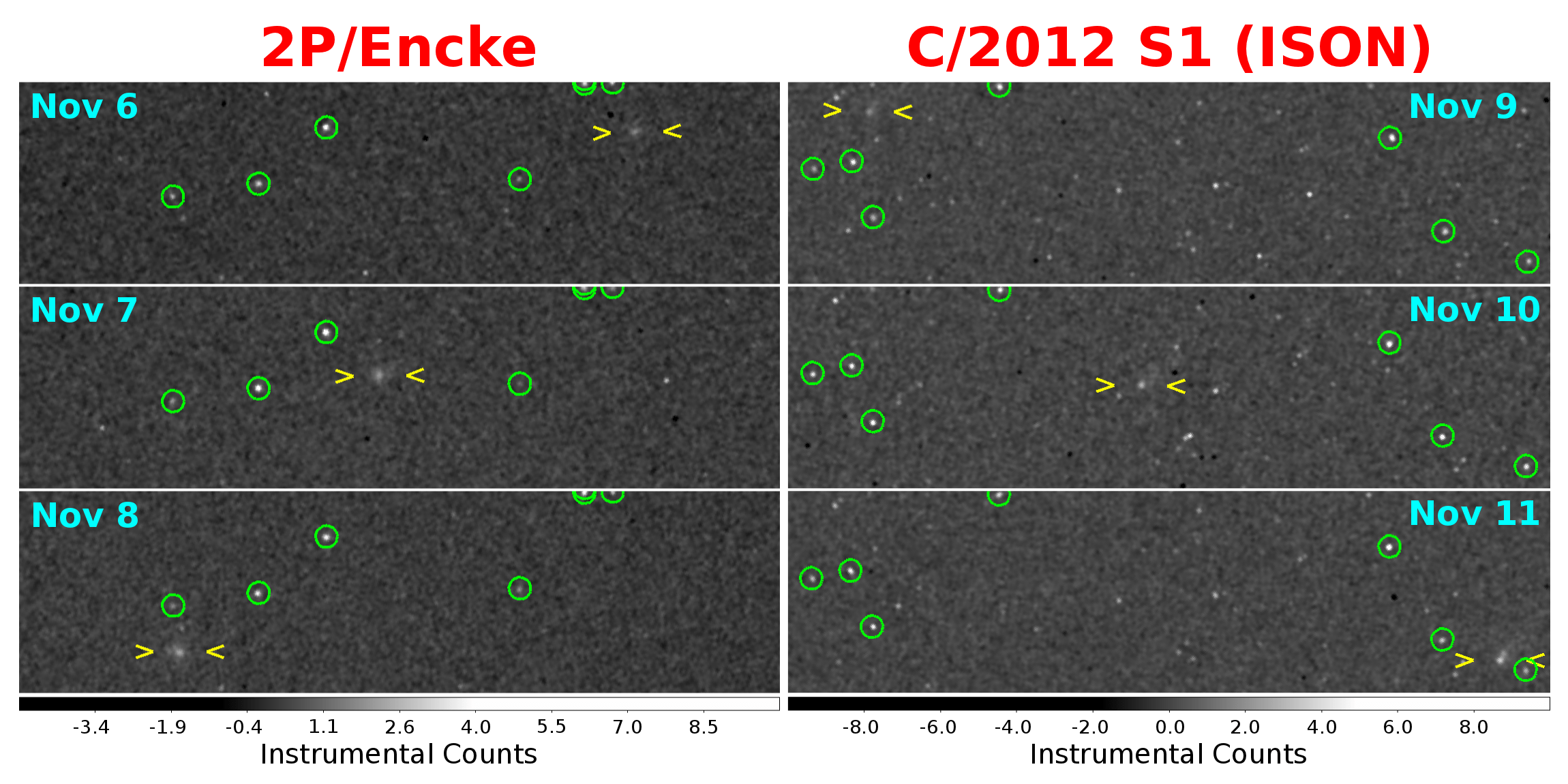

The frenzy for all things ISON reached a crescendo on U.S. Thanksgiving Day November 28th 2013, as ISON passed just 1.1 million kilometres from the surface of the Sun. Unfortunately, what emerged was a sputtering ember of the comet formerly known as ISON, which faded from view just as it was slated to reenter the dawn sky.

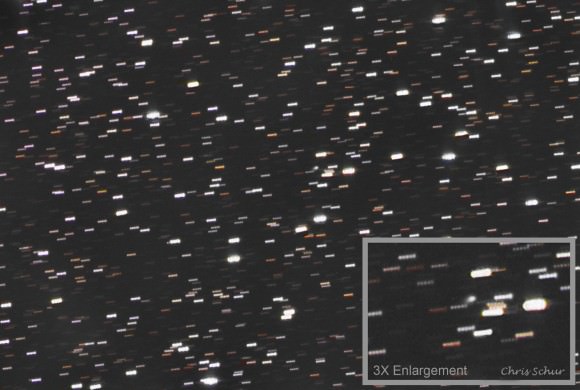

Hey, we were crestfallen as well… we had our semi-secret dark sky site pre-selected for ISON imaging post-perihelion and everything. Despite heroic searches by ground and space-based assets, we’ve yet to see any compelling recoveries of Comet ISON post-perihelion.

This week, however, Comet ISON may put on its last hurrah, in the form of a minor meteor shower. We have to say from the outset that we’re highly skeptical that an “ISON-id meteor outburst” will grace the skies. Known annual showers are fickle enough, and it’s nearly impossible to predict just what might happen during a meteor shower with no past track record.

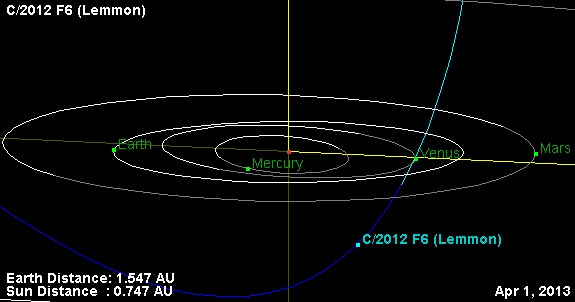

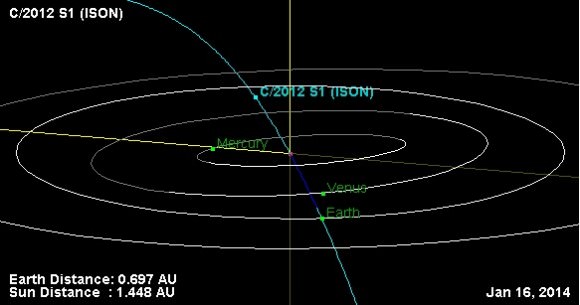

But you won’t see anything if you don’t try. If anything is set to occur, the night of January 15th into the 16th might just be the time to watch. This is because the Earth will cross the orbital plane of ISON’s path right around 9:00 PM EST/2:00 UT. Last year, ISON passed within 3.3 million kilometres of the Earth’s orbit on its inbound leg. Earlier last year, ISON was estimated to have been generating a prodigious amount of dust, at a rate of about 51,000 kilograms per minute. Any would-be fragments of ISON outbound would’ve passed closest to the Earth at 64 million kilometres distant on the day after Christmas last year. Veteran sky observer Bob King wrote about the prospects for catching ISON one last time during this month back in December 2013.

Another idea out there that is even more unlikely is the proposal that dust from Comet ISON may generate an uptick in noctilucent cloud activity. And already, a brief search of the internet sees local news reports attempting to tie every meteor observed to ISON this week, though no conclusive link to any observed fireball has been made.

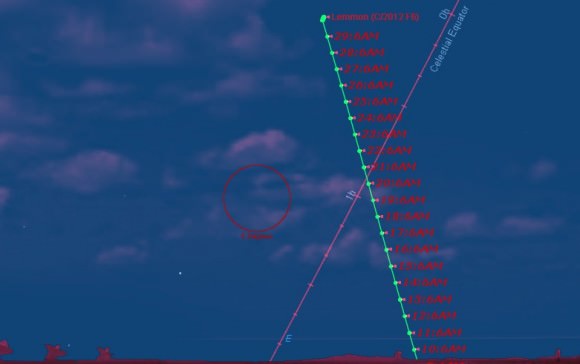

The radiant to watch for any possible “ISON-ids” sits near the +3.5 magnitude star Eta Leonis in the sickle of Leo. Robert Lundsford of the American Meteor Society notes in a recent posting that any ISON-related meteors would pass through our atmosphere at a moderate 51 kilometres a second, with a visible duration of less than one second.

Note that meteor activity has another strike against it, as the Moon reaches Full on the same night. In fact, the Full Moon of Wednesday January 15th sits in the constellation Gemini,just 32 degrees away from the suspect radiant!

Another caveat is in order for any remaining dooms-dayers: no substantial fragments of ISON are (or ever were) inbound and headed towards our fair planet. Yes, we’re seeing rumblings to this effect in the pseudoscience netherworlds of ye ole Internet, along with ideas that ISON secretly survived, NASA “hid” ISON, ISON cloaked like a Romulan Bird of Prey, you name it. Just dust grains, folks… a good show perhaps, but nothing more.

As near as we can tell, talk of a possible meteor shower generated from Comet ISON goes all the way back to a NASA Science News article online from April 2013. Radio observers of meteor showers should be alert for a possible surge in activity this week as well, and it may be the case that more radio “pings” will be noted than visual activity what with the light-polluting Full Moon in the sky. The radiant for any would-be “ISON-ids” transits highest in the sky for northern hemisphere observers at around 2 AM local.

But despite what it has going against it, we’d be thrilled if ISON put on one last show anyhow. It’s always worth watching for meteor activity and noting the magnitude and from whence the meteor came to perhaps note the pedigree as to the shower it might belong to.

The next annual dependable meteor shower won’t be until the night of April 21st to the 22nd, when the Spring Lyrids are once again active. And this year may just offer a special treat on May 24th, when researchers have predicted that the Earth may encounter debris streams laid down by Comet 209P LINEAR way back in 1803 and 1924… Camelopardalids, anyone? Now, that’s an exotic name for a meteor shower that we’d love to see trending!

-Catch sight of any “ISON-ids?” we’d love to see ‘em… be sure to post said pics at Universe Today’s Flickr pool.