As NASA and the European Space Agency prepare their remote photojournalists – Mars Express, Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the Curiosity and Opportunity rovers – to capture photos of Comet ISON’s flyby of Mars early next week, amateur astronomers continue to monitor and photograph the comet from backyard observatories across the blue Earth. Several recent color photos show ISON’s bright head or nucleus at the center of a puffy, green coma. Green’s a good omen – a sign the comet’s getting more active as it enters the realm of the inner solar system and sun’s embrace.

Sunlight beating down on the comet’s nucleus (core) vaporizes dust-impregnated ice to form a cloud or coma, a temporary atmosphere of water vapor, dust, carbon dioxide, ammonia and other gases. Once liberated , the tenuous haze of comet stuff rapidly expands into a huge spherical cloud centered on the nucleus. Comas are typically hundreds of thousands of miles across but are so rarified you could wave your hand through one and not feel a thing. The Great Comet of 1811 sported one some 864,000 miles (1.4 million km) across, nearly the same diameter as the sun!

Among the materials released by solar heating are cyanogen and diatomic carbon. Both are colorless gases that fluoresce a delicious candy-apple green when excited by energetic ultraviolet light in sunlight.

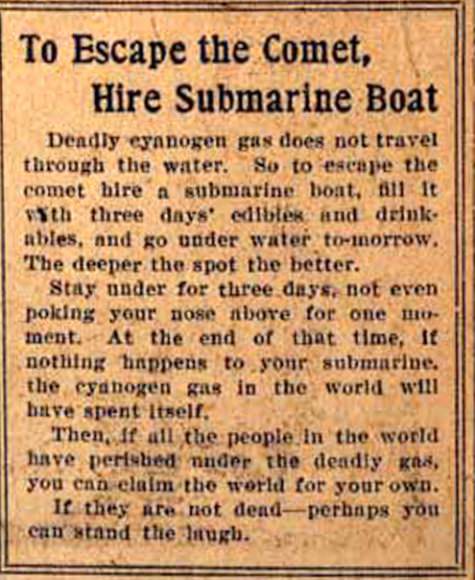

Cyanogen smells pleasantly of almonds, but it’s a poisonous gas composed of one atom each of carbon and nitrogen. Diatomic carbon or C2 is equally unpleasant. It’s a strong, corrosive acid found not only in comets but also created as a vapor in high-energy electric arcs. But nature has a way of taking the most unlikely things and fashioning them into something beautiful. If you’re concerned about the effects of cometary gas and dust on people, rest easy. They’re spread too thinly to touch us here on Earth. That didn’t stop swindlers from selling “comet pills” and gas masks to protect the public from poisoning during the 1910 return of Halley’s Comet. Earth passed through the tail for six hours on May 19 that year. Amazingly, those who took the pills survived … as did everyone else.

While Comet ISON is still too faint for visual observers to discern its Caribbean glow, that will change as it beelines for the sun and brightens. If you could somehow wish yourself to Mars in the next few days, I suspect you’d easily see the green coma through a telescope. The comet – a naked eye object at magnitude 2.5-3 – glows low in the northern sky from the Curiosity rover’s vantage point 4.5 degrees south of the Martian equator.

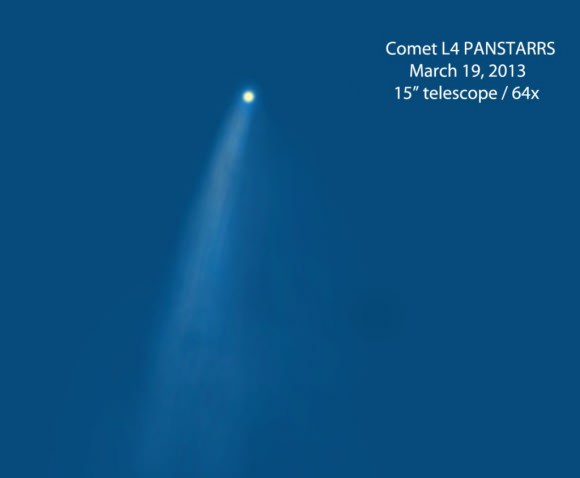

I’ve noticed that when a comet reaches about 7th magnitude, the green coloration becomes apparent in 8-inch (20 cm) and larger telescopes. Bright naked eye comets often display multiple subtle colors that change chameleon-like over time. Dust tails, formed when sunlight pushes dust particles downwind from the coma, glow pale yellow. Gusty solar winds sweep back molecules from the coma into a second “ion” tail that glows pale blue from jazzed up carbon monoxide ions fluorescing in solar UV.

During close encounters with the sun, millions of pounds of dust per day boil off a comet’s nucleus, forming a small, intensely bright, yellow-orange disk in the center of the coma called a false nucleus. Earlier this year, when Comet C/2011 L4 PANSTARRS emerged into the evening sky after perihelion, not only was its yellow tail apparent to binocular users but the brilliant false nucleus glowed a lovely shade of lemon in small telescopes.

With ISON diving much closer to the sun than L4 PANSTARRS, expect a full color palette in the coming weeks. While it may not be easy being green for Sesame Street’s Kermit the Frog, comets do it with aplomb.