One of the best yearly meteor showers contends with the nearly Full Moon this year, but don’t despair; you may yet catch the Geminids.

The Geminid meteor shower peaks next week on the evening of Tuesday night into Wednesday morning, December 13th/14th. The Geminids are always worth keeping an eye on in early through mid-December. As an added bonus, the radiant also clears the northeastern horizon in the late evening as seen from mid-northern latitudes. The Geminids are therefore also exceptional among meteor showers for displaying early evening activity.

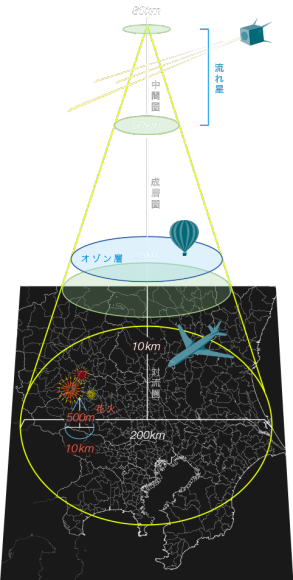

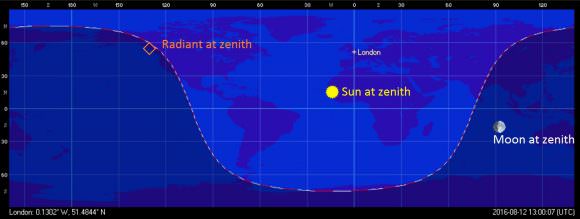

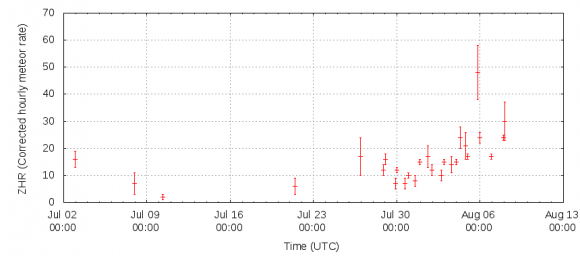

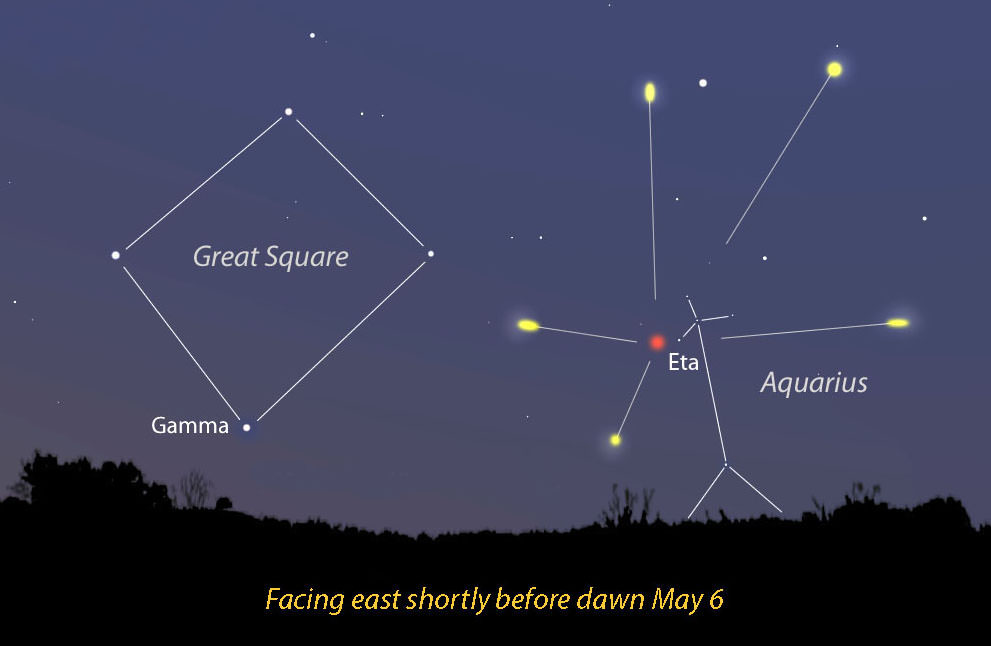

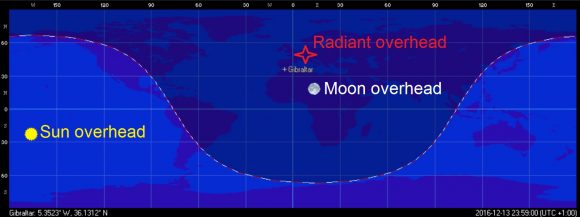

First, though, here is the low down of the specifics for the 2016 Geminids: the Geminid meteors are expected to peak on December 13th/14th at midnight Universal Time (UT), favoring Western Europe. The shower is active for a two week period from December 4th to December 17th and can vary with a Zenithal Hourly Rate (ZHR) of 50 to 80 meteors per hour, to short outbursts briefly topping 200 per hour. In 2016, the Geminids are expected to produce a maximum ideal ZHR of 120 meteors per hour. The radiant of the Geminids is located at right ascension 7 hours 48 minutes, declination 32 degrees north at the time of the peak, in the constellation of Gemini.

The Moon is a 98% illuminated waning gibbous just 20 degrees from the radiant at the peak of the Geminids, making 2016 an unfavorable year for this shower. In previous years, the Geminids produced short outbursts topping 200 per hour, as last occurred in 2014.

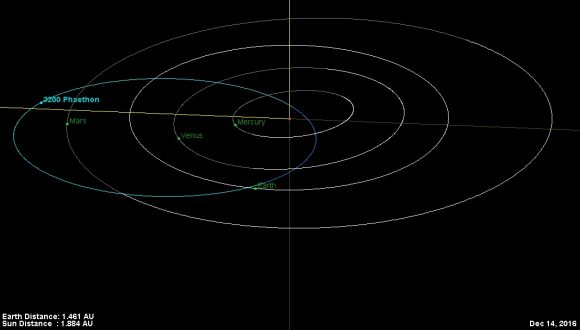

The Geminid meteors strike the Earth at a relatively slow velocity of 35 kilometers per second, and produce many fireballs with an r vaule of 2.6. The source of the Geminid meteors is actually an asteroid: 3200 Phaethon.

A moderate shower in the late 20th century, the Geminids have increased in intensity during the opening decade and a half of the 21st century, surpassing the Perseids for the title of the top annual meteor shower.

The Geminid shower seems to have breached the background sporadic rate around the mid-19th century. Astronomers A.C. Twining and R.P. Greg observing from either side of the pond in the United States and the United Kingdom both first independently noted the shower in 1862.

Orbiting the Sun once every 524 days, 3200 Phaethon wasn’t identified as the source of the Geminids until 1983. The asteroid is still a bit of a mystery; reaching perihelion just 0.14 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun, (interior to Mercury’s orbit) 3200 Phaethon is routinely baked by the Sun. Is it an inactive comet nucleus? Or a ‘rock comet’ in a transitional state?

Observing meteors is as simple as setting out in a lawn chair, laying back and watching with nothing more technical than a good ole’ Mk-1 pair of human eyeballs. Our advice for 2016 is to start watching early, like say this weekend, before the Moon reaches Full on Wednesday, December 14th. This will enable you to watch for the Geminids after morning moonset under dark skies pre-peak, and before moonrise on evenings post-peak.

Two other minor showers are also active next week: the Coma Bernicids peaking on December 15th, and the Leo Minorids peaking on December 19th. If you can trace a suspect meteor back to the vicinity of the Gemini ‘twin’ stars of Castor and Pollux, then you’ve most likely spied a Geminid and not an impostor.

And speaking of the Moon, next week’s Full Moon is not only known as the Full Cold Moon (For obvious reasons) from Algonquin native American lore, but is also the closest Full Moon to the December 21st, northward solstice. This means that next week’s Full Moon rides highest in the sky for 2016, passing straight overhead for locales sited along latitude 17 degrees north, including Guatemala City and Mumbai, India.

Photographing the Geminids is also as simple as setting a camera on a tripod and taking wide-field exposures of the sky. We like to use an intervalometer to take automated sequences about 30 seconds to 3 minutes in length. Said Full Moon will most likely necessitate shorter exposures in 2016. Keep a fresh set of backup batteries handy in a warm pocket, as the cold December night will drain camera batteries in a pinch.

Looking to contribute some meaningful scientific observations? Report those meteor counts to the International Meteor Organization.

And although the Geminids might be a bust in 2016, another moderate shower, the Ursids has much better prospects right around the solstice… more on that next week!