[/caption]

It wasn’t that long ago that astronomers began discovering the first planets around other stars. But as the field of exoplanetary astronomy explodes, astronomers have begun looking to the future and considering the possibility of detecting moons around these planets. Surprisingly, the potential for doing so may not be that far off.

Before exploring how we might detect satellites of distant planets, astronomers must first attempt to get an understanding of what they may be looking for. Fortunately, this question ties in well with the rapidly developing understanding of how solar systems form.

In general, there are three mechanisms by which planets may obtain satellites. The simplest is for them to simply form together from a single accretion disk. Another is that a massive impact may knock material off of a planet which forms into a satellite as astronomers believe happened with our own Moon. Some estimates have indicated that such impacts should be frequent and as many as 1 in 12 Earth like planets may have formed moons in this way. Lastly, a satellite may be a captured asteroid or comet as is likely for many of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn.

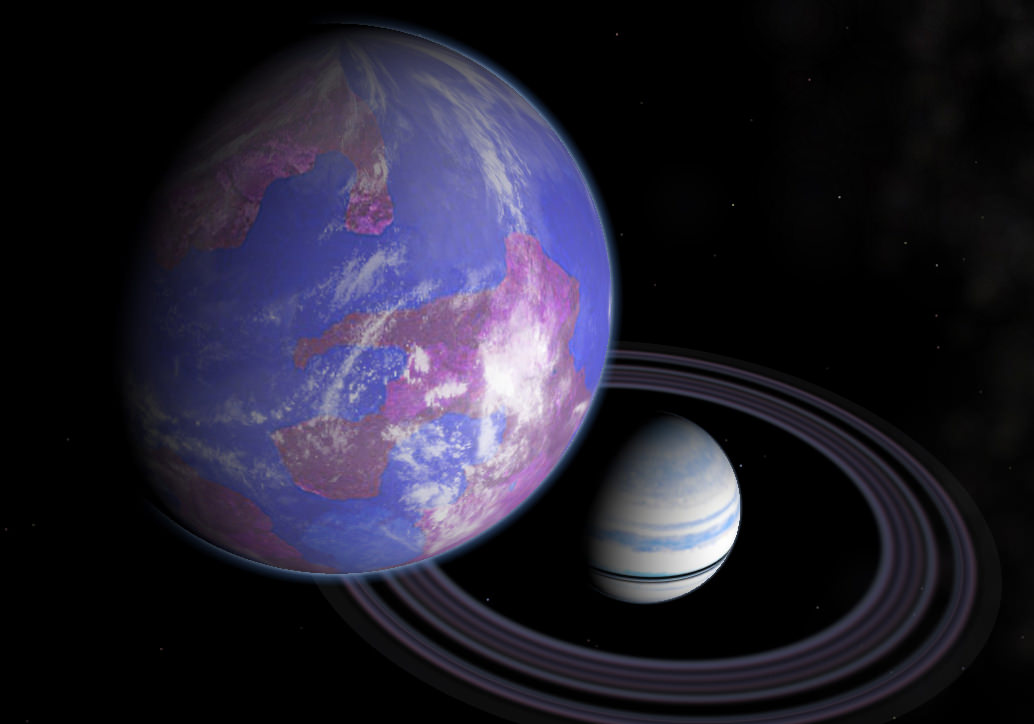

Each of these cases produces a different range of masses. Captured bodies are likely to be the smallest and therefor are unlikely to be detectable in the near future. Impact generated moons are expected to only be able to form bodies with 4% of the total mass of the planet and as such, are rather limited as well. The largest moons are thought to form in the disks around forming Jupiter like planets. These are the most likely to be detectable.

The first method by which astronomers may detect such moons is by the changes they would make in the wobble of the star that has been used to detect many extrasolar planets to date. Astronomers have already studied how a pair of binary stars may affect a binary star system may have on a third star it orbits. If the binary star is swapped out for a planet and a moon it turns out that the easiest systems to detect are massive moons that are distant from the planet, but close to the parent star. However, except in extreme cases, the amount of wobble that the pair could induce in the star is so small that it would be swamped by the convective motion of the star’s surface, making detection through this method nearly impossible.

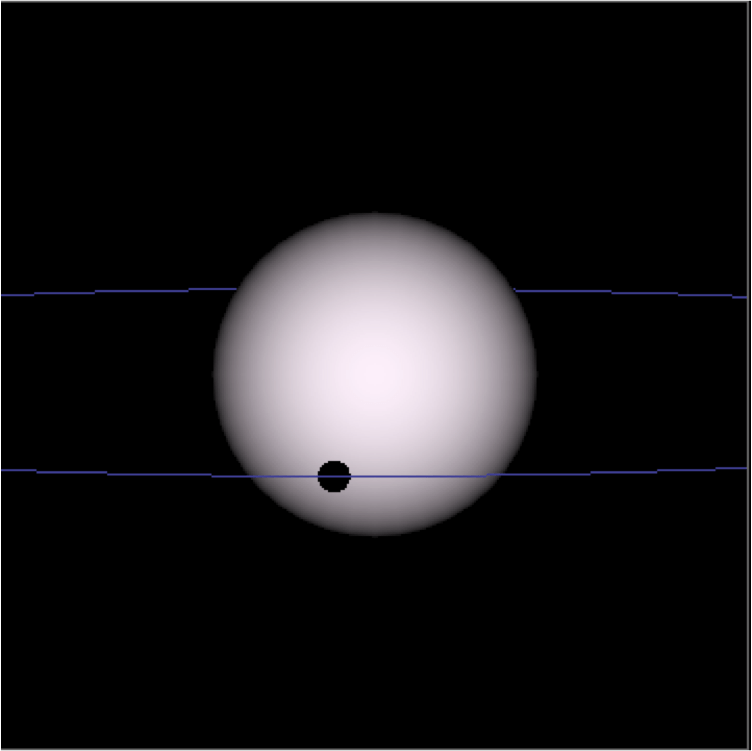

Astronomers have begun detecting large numbers of exoplanets by transits, where the planet causes minor eclipses. Could astronomers also detect the presence of moons this way? In this case, the limit on detection would again be based on the size of the moon. Currently, the Kepler satellite is expected to detect planets similar in mass to Earth. If moons exist around a super-Jovian planet that are also similar in size to Earth, they too should be detected. However, forming moons this large is difficult. The largest moon in the solar system in Ganymede which is 40% of the diameter of Earth, putting it modestly below current detection thresholds, but potentially in reach of future exoplanet missions.

However, direct detection of the eclipses caused by transits isn’t the only way transits could be used to discover exomoons. In the past few years, astronomers have begun using the wobble of other planets on the ones they had already discovered to infer the existence of other planets in the system in the same way the gravitational tug of Neptune on Uranus allowed astronomers to predict Neptune’s existence before it was discovered. A sufficiently massive moon could cause detectable variations in when the transit of the planet would begin and end. Astronomers have already used this technique to place limits on the mass of potential moons around exoplanets HD 209458 and OGLE-TR-113b at 3 and 7 Earth masses respectively.

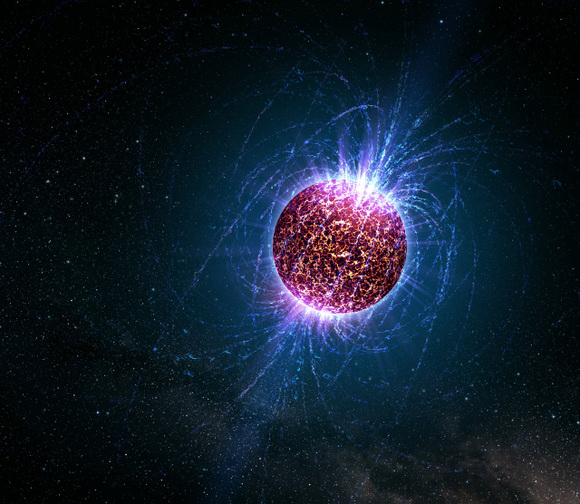

The first discovered exoplanet was discovered around a pulsar. The tug of this planet caused variation of the regular pulsation of the pulsar’s beat. Pulsars often beat hundreds to thousands of times per second and as such, are extremely sensitive indicators of the presence of planets. The pulsar PSR B1257+12 is known to harbor one planet that is a mere 0.04% the mass of Earth, which is well below the mass threshold of many moons. As such, variations in these systems, caused by moons would be potentially detectable with current technology. Astronomers have already used it to search for moons around the planet orbiting PSR B1620-26 and ruled out moons more than 12% the mass of Jupiter within half an Astronomical Unit (the distance between the Earth and Sun or 93 million miles) of the planet.

The last method by which astronomers have detected planets that could potentially be used for exomoons is direct observation. Since direct imaging of exoplanets has only become realized in the past few years, this option is likely still a ways off, but future missions like the Terrestrial Planet Finder Coronagraph may put it into the realm of possibility. Even if the moon is not fully resolved, the offset of the center of the dot of the pair may be detectable with current instruments.

Overall, if the explosion of knowledge on planetary systems continues, astronomers should be capable of detecting exomoons within the near future. The possibility already exists for some cases, like pulsar planets, but due to their rarity, the statistical likelihood of finding a planet with a sufficiently large moon is low. But as equipment continues to improve, making detection thresholds lower for various methods, the first exomoons should come into view. Undoubtedly, the first ones will be large. This will beg the question of what sorts of surfaces and potentially atmospheres they may have. In turn, this would inspire more questions about what life may exist.

Source:

The Detectability of Moons of Extra-Solar Planets – Karen M. Lewis