If you follow some of my other shows, like Astronomy Cast and the Weekly Space Hangout. Of course you do, what a ridiculous thing to say… “if”. Anyway, since you follow those other shows, you know I’m currently obsessed with an upcoming observatory called the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope.

Obsessions are best when they’re shared. So today, I invite you to become as obsessed as I am about the LSST.

In the past, astronomers focused on building bigger telescopes at more remote locations so they could peer more deeply into the past, to resolve the faintest objects, to see right to the edge of the observable Universe.

But there’s a whole other dimension to the Universe: time. And by taking advantage of time, astronomers have made some of the most momentous discoveries in the history of astronomy.

The Large Synoptic Survey Telescope is all about time. Watching the sky over and over, night after night, watching for anything that changes.

First, let’s talk about some of the kinds of discoveries that can be made when you’re watching the sky for changes.

Perhaps the best example of this is the Mira Variable. These are red giants at the very end of their stellar evolution, almost out of usable hydrogen to burn in their cores. As their stellar flame flickers out, the light pressure can no longer hold against the gravity pulling the star inward. The star compresses in on itself, raising the temperature and pressure, allowing more fusion. It flares up again, and brightens in our sky.

Astronomers discovered that there’s a very specific relationship to the brightness and rate that this brightening happens. In other words, if you know how often a Mira variable flares up, you know how intrinsically bright it is. And if you know how bright it is, you can calculate how far away it is. Even in other galaxies.

That’s what Edwin Hubble did when he surveyed Mira variables in other galaxies. He discovered that most galaxies are actually speeding away from us in all directions, leading to the theory of the Big Bang.

Thanks to time, we understand that we life in an expanding Universe that originated from a single point, 13.8 billion years ago.

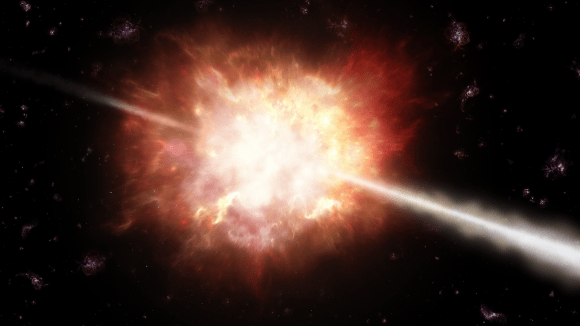

Let me give you another example: the discovery of gamma ray bursts. In the 1960s, the US launched a group of satellites as part of the Vela Mission. They had no astronomical purpose, they were designed to watch for the specific gamma ray signature from an unauthorized nuclear weapons test. But instead of nuclear explosions, they detected massive blasts of gamma radiation coming from deep space. These blasts only last for a few seconds and then fade away, leaving a faint afterglow that also fades.

We now know that gamma ray bursts mark the deaths of the largest stars in the Universe, and the formations of new black holes. Other gamma ray bursts signal the collisions of exotic stellar remnants, like neutron stars and white dwarfs.

I can give you many more examples, where the dimension of time lead to a discovery in astronomy:

In 1930, Clyde Tombaugh compared pairs of photographic plates, switching back and forth over and over, looking for any object that moved position. This was how he discovered Pluto. In fact, this same technique is used by astronomers to find other dwarf planets, asteroids and comets to this day.

Astronomers return again and again to galaxies in the night sky, looking for any that have a new star in them. This is a tell tale sign of a supernova, the explosion of a star much more massive than our Sun. Some of these supernovae allowed astronomers to discover dark energy, that the expansion of the Universe is accelerating.

This is what time can help us discover.

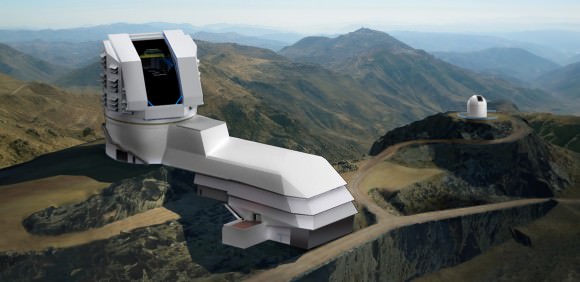

Now, on to the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope. The observatory is currently under construction in north-central Chile, where many of the world’s most powerful telescopes are located.

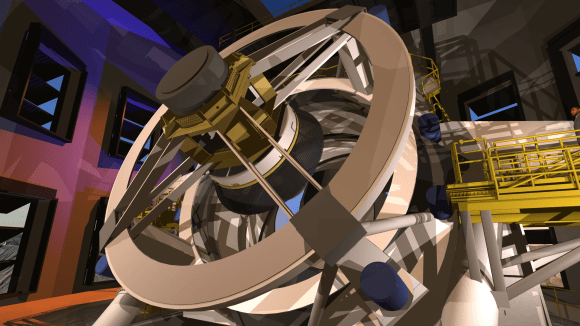

Its main mirror is 8.4 meters across. Just for comparison, ESO’s Very Large Telescopes are 8.2 metres across. The Gemini Observatories are 8.1 metres across. The Keck Observatory is 10 metres wide. What I’m saying here, is that the LSST is plenty big.

But that’s not its most important feature. LSST is fast. When I say fast, I’m saying this in the astronomical sense, which means that it can gather a lot of light over a wide area on the sky in a very short amount of time. While Keck, for example, can focus incredibly deeply at a tiny spot in the sky, LSST gulps light across a huge region of the sky.

It’ll be able to see 3.5-degrees of the sky, every time it takes a picture. The Sun and the Moon are about 0.5-degrees across in the sky, so imagine a grid 7 moons across and 7 moons high.

It’ll take a 15-second exposure every 20 seconds. In the amount of time you’ll spend watching this video, the LSST could have taken dozens of high resolution images of the sky.

In fact, it’ll completely image the available sky every few nights. And then petabytes of data will be released onto the internet, available for astronomers to pore over.

Want to find asteroids, just look through the LSST records. Want to know how fast the Universe is expanding, dig through the data. LSST is going to look everywhere and anywhere every couple of nights, and then provide this data to scientists to make discoveries.

Assuming the construction isn’t delayed, the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope should see first light in 2019. Shortly after that, it’ll be disgorging mountains of astronomical data onto the internet.

And shortly after that, I suspect, we’ll start to hear everything the Universe was doing when we weren’t watching before. Because now, thanks to LSST, we’ll be watching all the time.

Confusion between Mira and Cepheid variables in paragraph 1. The Cepheids are the basis of the extragalactic distance scale based on their period-luminosity relationship, as discovered by Henrietta Leavitt in 1912.

Concur w/timk: Mira variables are stars in the late stages of stellar life, but Cepheid variables are what Edwin Hubble used. Mira variables are not consistent in their brightness curves, while Cepheids are remarkably so which is what allows them to be used as standard candles for all distances where we can resolve them individually.

New toyyyys!

I, for one, am looking forward to being able to wallpaper the rumpus room with an LSST deep-field view where the Full Moon would be half a meter across. Of course I would then add a glow-in-the-dark decal of said Moon at said resolution, and instantly become the coolest dad my kids have ever known.

Maybe. ^_^;;