[/caption] There's not a lot happening on the sun these days, at least in the sunspot department. "We're experiencing a very deep solar minimum," says solar physicist Dean Pesnell of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. In 2008, no sunspots were observed on 266 of the year's 366 days (73 percent). Sunspot counts for 2009 have dropped even lower, percentage-wise. As of March 31st, there were no sunspots on 78 of the year's 90 days (87 percent). Those who keep an eye on the sun say this is the quietest sun in almost a century. So, what does this all mean?

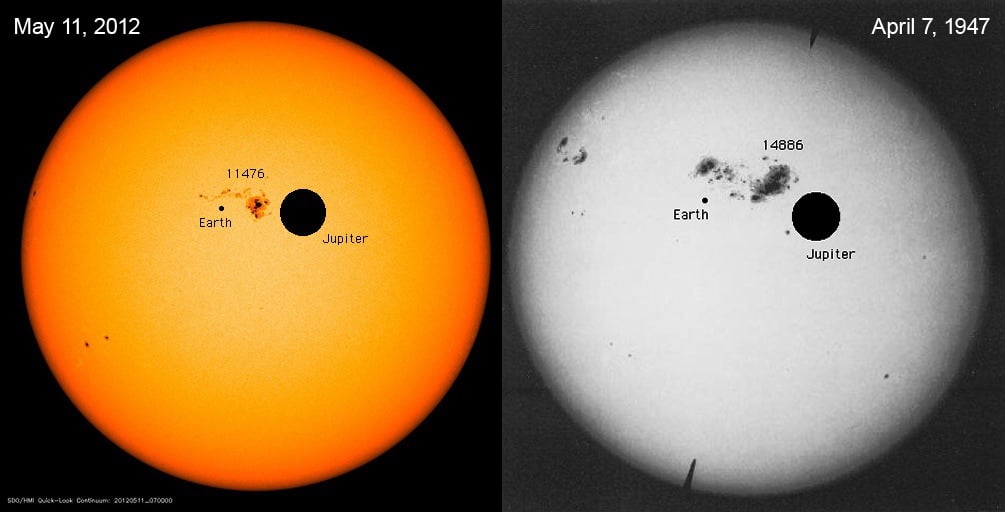

Sunspots are planet-sized islands of magnetism on the surface of the sun, and they are sources of solar flares, coronal mass ejections, and intense UV radiation. The sun has a natural cycle of about 11 years of high and low sunspot activity. This was discovered by German astronomer Heinrich Schwabe in the mid-1800s. Plotting sunspot counts, Schwabe saw that peaks of solar activity were always followed by valleys of relative calm—a clockwork pattern that has held true for more than 200 years.

The current solar minimum is part of that pattern. In fact, it's right on time. But is it supposed to be this quiet? [caption id="attachment_28459" align="aligncenter" width="249" caption="The sunspot cycle from 1995 to the present. The jagged curve traces actual sunspot counts. Smooth curves are fits to the data and one forecaster's predictions of future activity. Credit: David Hathaway, NASA/MSFC"]

[/caption] Measurements by the Ulysses spacecraft reveal a 20 percent drop in solar wind pressure since the mid-1990s—the lowest point since such measurements began in the 1960s. The solar wind helps keep galactic cosmic rays out of the inner solar system. With the solar wind flagging, more cosmic rays penetrate the solar system, resulting in increased health hazards for astronauts. Weaker solar wind also means fewer geomagnetic storms and auroras on Earth.

Careful measurements by several NASA spacecraft have also shown that the sun's brightness has dimmed by 0.02 percent at visible wavelengths and a whopping 6 percent at extreme UV wavelengths since the solar minimum of 1996. Radio telescopes are recording the dimmest "radio sun" since 1955.

All these lows have sparked a debate about whether the ongoing minimum is extreme or just an overdue correction following a string of unusually intense solar maxima.

"Since the Space Age began in the 1950s, solar activity has been generally high," said forecaster David Hathaway of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center. "Five of the ten most intense solar cycles on record have occurred in the last 50 years. We're just not used to this kind of deep calm."

Deep calm was fairly common a hundred years ago. The solar minima of 1901 and 1913, for instance, were even longer than what we're experiencing now. To match those minima in depth and longevity, the current minimum will have to last at least another year.

In a way, the calm is exciting, says Pesnell. "For the first time in history, we're getting to observe a deep solar minimum." A fleet of spacecraft — including the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), the twin probes of the Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO), and several other satellites — are all studying the sun and its effects on Earth. Using technology that didn't exist 100 years ago, scientists are measuring solar winds, cosmic rays, irradiance and magnetic fields and finding that solar minimum is much more interesting than anyone expected.

Modern technology cannot, however, predict what comes next. Competing models by dozens of solar physicists disagree, sometimes sharply, on when this solar minimum will end and how big the next solar maximum will be. The great uncertainty stems from one simple fact: No one fully understands the underlying physics of the sunspot cycle.

And the only thing scientists can do it to keep watching. Pesnell believes sunspot counts should pick up again soon, "possibly by the end of the year," to be followed by a solar maximum of below-average intensity in 2012 or 2013.

Source:

NASA

Universe Today

Universe Today