Many stars die spectacularly when they explode as supernovae. During these violent explosions, they leave behind thick, chaotic clouds of debris shaped like cauliflowers. But supernova remnant Pa 30 looks nothing like that.

Instead of the usual remains, long, straight filaments radiate from a central point of Pa 30 like trails from a sparkler frozen mid-burst. For years, astronomers struggled to explain why this supernova remnant seemed to trace back to a “guest star” seen in 1181 by Chinese and Japanese observers. Now, Eric Coughlin at Syracuse University has an answer: the star tried to explode but didn’t quite succeed.

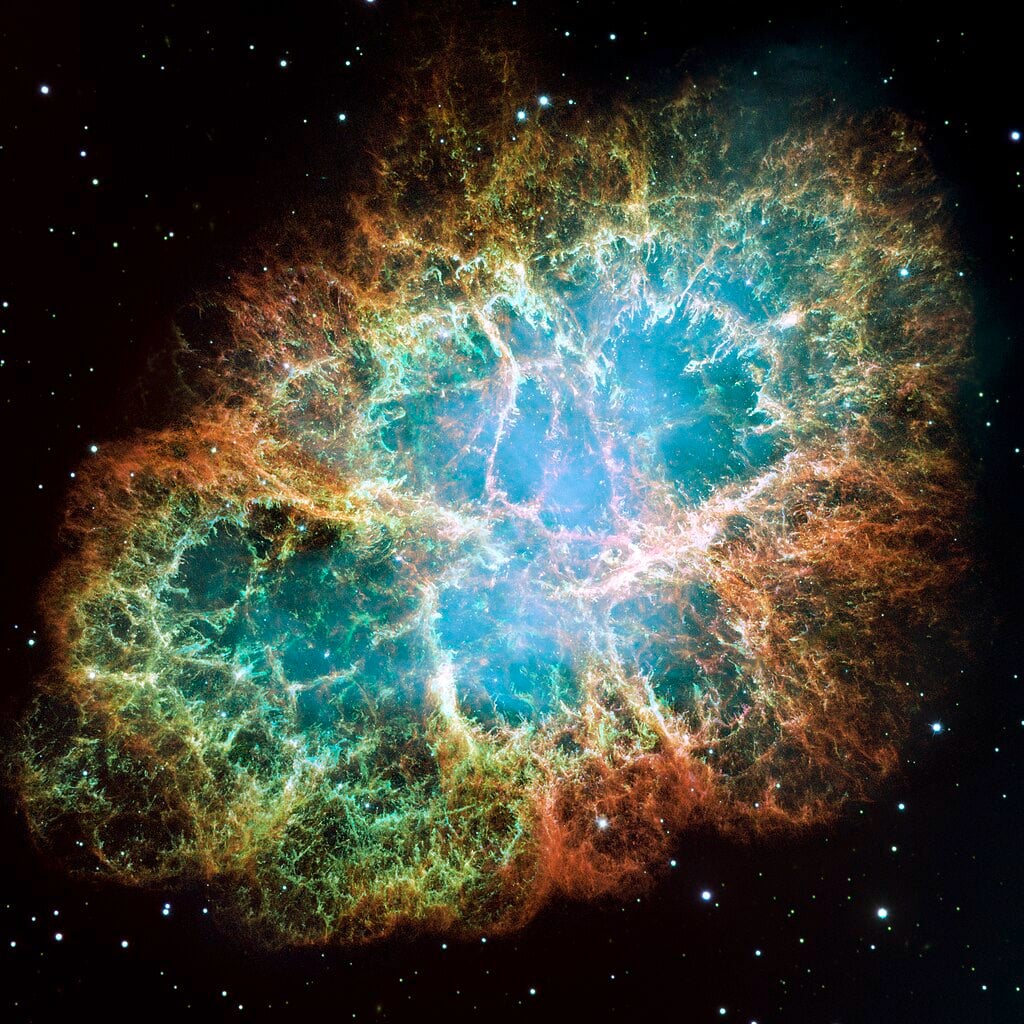

This is a composite image of SNR 1181, the remains of an explosion hundreds of years ago caused by the merger of two stars (Credit : NASA/Chandra)

This is a composite image of SNR 1181, the remains of an explosion hundreds of years ago caused by the merger of two stars (Credit : NASA/Chandra)

When white dwarfs detonate as Type Ia supernovae, they typically obliterate themselves entirely, creating expanding debris clouds. But Pa 30’s progenitor only partially exploded. The nuclear burning near the star’s surface never transitioned into a full supersonic detonation. Instead, it fizzled, leaving behind a hyper-massive white dwarf still intact at the centre.

Here’s where things get interesting. That surviving white dwarf didn’t just sit quietly. It began launching an extraordinarily fast wind, moving at roughly 15,000 kilometres per second and was enriched with heavy elements forged during the failed explosion. This wind, far denser than the surrounding gas, slammed outward into space.

At the boundary between the dense wind and lighter surrounding material, conditions were perfect for the Rayleigh–Taylor instability to operate. This is the same fluid physics that creates mushroom clouds when heavy fluid pushes into light fluid, plumes like fingers develop. In Pa 30, those plumes became the long filaments astronomers observe today.

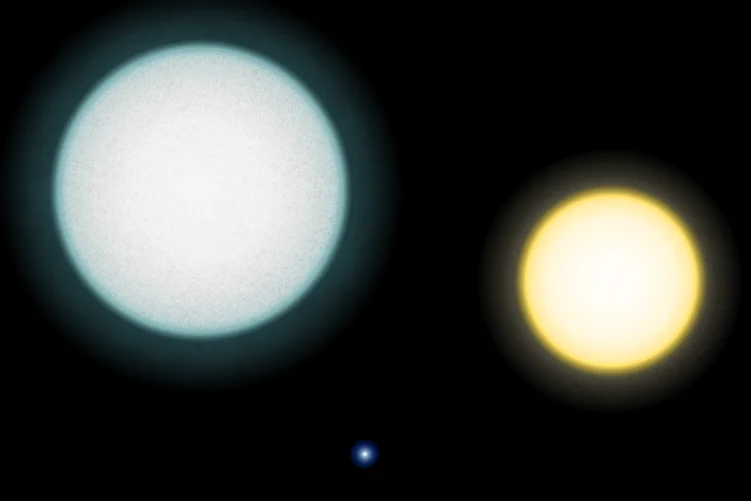

A comparison between the white dwarf IK Pegasi B (centre), its A-class companion IK Pegasi A (left) and the Sun (right). This white dwarf has a surface temperature of 35500 K (Credit : RJ Hall)

A comparison between the white dwarf IK Pegasi B (centre), its A-class companion IK Pegasi A (left) and the Sun (right). This white dwarf has a surface temperature of 35500 K (Credit : RJ Hall)

But why didn’t they shred apart? Normally, a second process where the mixing that makes smoke curl and twist, tears the fingers into chaotic wisps. It’s why most supernova remnants look messy. The dense wind in Pa 30 was so much heavier than the surrounding gas that this second instability never kicked in. The filaments just kept stretching outward, fed continuously by the wind, leaving Pa 30 with its distinctive firework appearance.

Coughlin’s paper includes simulations showing that high density contrasts can produce exactly these structures. The research also draws an unexpected parallel with declassified photographs from the 1962 Kingfish nuclear test that shows similar filamentary patterns forming initially after detonation before evolving into cauliflower shapes. The difference is timing, Pa 30’s wind fed filaments kept growing rather than quickly morphing into chaos.

This kind of failed explosion represents a distinct subclass called Type Iax supernovae. They’re rare but increasingly recognised. Coughlin suspects Pa 30 isn’t unique with similar filamentary structures that might appear in other astrophysical phenomena with dense winds, including tidal disruption events when black holes shred stars.

Pa 30 is one of few events in deep space where modern modelling connects directly to historical observations. The guest star of 1181 has become a detailed case study in how stars sometimes die not with a bang, but with a complicated whimper that leaves behind surprising beauty.

Source : Failed Supernova, Cosmic Fireworks

Universe Today

Universe Today