[/caption] The Swift spacecraft is doing double duty these days. Normally, the Gamma-ray Explorer satellite is on the lookout for high-energy outbursts and cosmic explosions. But now Swift is also monitoring Comet Lulin as it comes closer to Earth. For the first time, astronomers are seeing simultaneous ultraviolet and X-ray images of a comet. "The comet is releasing a great amount of gas, which makes it an ideal target for X-ray observations," said Andrew Read, also at Leicester. And the ultraviolet data shows that Lulin is also shedding a huge amount of water, about 800 gallons of water each second!

"We won't be able to send a space probe to Comet Lulin, but Swift is giving us some of the information we would get from just such a mission," said Jenny Carter, at the University of Leicester, U.K., who is leading the study.

Comets are called "dirty snowballs," as they are clumps of frozen gases mixed with dust. As comets venture near the sun, gas and dust are released. Comet Lulin, which is formally known as C/2007 N3, was discovered last year by astronomers at Taiwan's Lulin Observatory. The comet is now faintly visible from a dark site. Lulin will pass closest to Earth -- 38 million miles, or about 160 times farther than the moon -- late on the evening of Feb. 23 for North America.

On Jan. 28, Swift trained its Ultraviolet/Optical Telescope (UVOT) and X-Ray Telescope (XRT) on Comet Lulin. "The comet is quite active," said team member Dennis Bodewits, a NASA Postdoctoral Fellow at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md. "The UVOT data show that Lulin was shedding nearly 800 gallons of water each second." That's enough to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool in less than 15 minutes. [caption id="attachment_25981" align="aligncenter" width="580" caption="Comet Lulin was passing through the constellation Libra when Swift imaged it. This view merges the Swift data with a Digital Sky Survey image of the star field. Credit: NASA/Swift/Univ. of Leicester/DSS (STScI, AURUA)/Bodewits et al."]

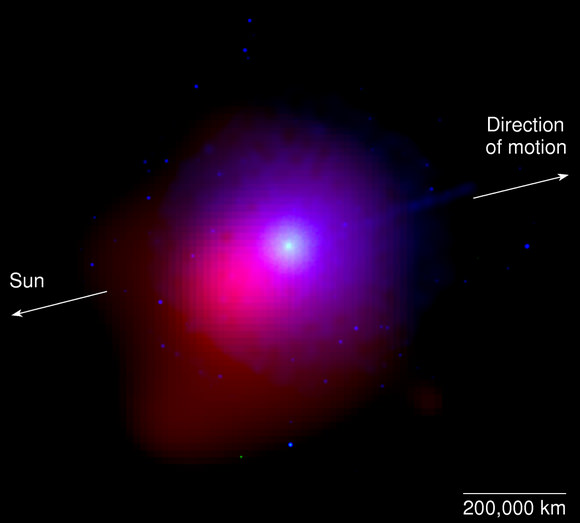

[/caption] Swift can't see water directly. But ultraviolet light from the sun quickly breaks apart water molecules into hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl (OH) molecules. Swift's UVOT detects the hydroxyl molecules, and its images of Lulin reveal a hydroxyl cloud spanning nearly 250,000 miles, or slightly greater than the distance between Earth and the moon.

The UVOT includes a prism-like device called a grism, which separates incoming light by wavelength. The grism's range includes wavelengths in which the hydroxyl molecule is most active. "This gives us a unique view into the types and quantities of gas a comet produces, which gives us clues about the origin of comets and the solar system," Bodewits explains. Swift is currently the only space observatory covering this wavelength range.

In the Swift images, the comet's tail extends off to the right. Solar radiation pushes icy grains away from the comet. As the grains gradually evaporate, they create a thin hydroxyl tail.

Farther from the comet, even the hydroxyl molecule succumbs to solar ultraviolet radiation. It breaks into its constituent oxygen and hydrogen atoms. "The solar wind -- a fast-moving stream of particles from the sun -- interacts with the comet's broader cloud of atoms. This causes the solar wind to light up with X rays, and that's what Swift's XRT sees," said Stefan Immler, also at Goddard.

This interaction, called charge exchange, results in X-rays from most comets when they pass within about three times Earth's distance from the sun. Because Lulin is so active, its atomic cloud is especially dense. As a result, the X-ray-emitting region extends far sunward of the comet.

"We are looking forward to future observations of Comet Lulin, when we hope to get better X-ray data to help us determine its makeup," noted Carter. "They will allow us to build up a more complete 3-D picture of the comet during its flight through the solar system."

Source: NASA

Universe Today

Universe Today