Free-floating rogue planets are intriguing objects. These planet-sized bodies adrift in interstellar space were predicted to exist in 1998, and since 2011 several orphan worlds have finally been detected. The leading theory on how these nomadic planets came to exist is that they were they ejected from their parent star system. But new research shows that there are places in interstellar space that might have the right conditions to form planets -- with no parent star required.

Astronomers from Sweden and Finland have found tiny, round, cold clouds in space that may allow planets to form within, all on their own. In a sense, planets could be born free.

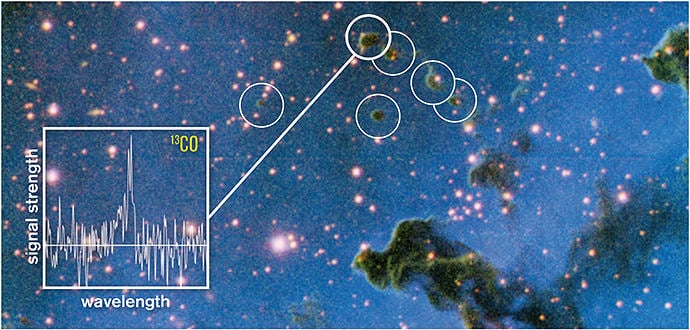

The team of astronomers studied the Rosette Nebula, a huge cloud of gas and dust 4,600 light years from Earth in the constellation Monoceros. They collected observations in radio waves with the 20-meter telescope at Onsala Space Observatory in Sweden, in submillimetre waves with APEX in Chile, and in infrared light with the New Technology Telescope (NTT) at ESO's La Silla Observatory in Chile.

"The Rosette Nebula is home to more than a hundred of these tiny clouds – we call them globulettes", says Gösta Gahm, astronomer at Stockholm University, who led the project. "They are very small, each with diameter less than 50 times the distance between the Sun and Neptune."

In previous observations, Gahm and his team were able to estimate that most of the globulettes are of planetary mass, less than 13 times Jupiter's mass. Now, they were able to get more reliable measures of mass and density for a large number of these objects, as well as precisely measuring how fast they are moving relative to their environment.

[caption id="attachment_104246" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

Onsala Space Observatory, the Swedish National Facility for Radio Astronomy. Via Chalmers University of Technology. [/caption]

"We found that the globulettes are very dense and compact," said team member Carina Persson, astronomer at Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden, "and many of them have very dense cores. That tells us that many of them will collapse under their own weight and form free-floating planets. The most massive of them can form so-called brown dwarfs."

Brown dwarfs, sometimes called failed stars, are bodies whose mass lies between that of planets and stars.

According to the team's paper, the tiny dark clouds are being thrown out of the Rosette Nebula, moving at high speed, about 80,000 kilometers per hour.

"If these tiny, round clouds form planets and brown dwarfs, they must be shot out like bullets into the depths of the Milky Way," said Gahm. "There are so many of them that they could be a significant source of the free-floating planets that have been discovered in recent years."

Previous research has predicted there might be 100,000 times more rogue planets in the Milky Way than stars.

And Gahm and his team say that during the history of the Milky Way, countless millions of nebulae like the Rosette have bloomed and faded away. From these, many globulettes would have formed.

"We think that these small, round clouds have broken off from tall, dusty pillars of gas which were sculpted by the intense radiation from young stars," said Minja Mäkelä, astronomer at the University of Helsinki. "They have been accelerated out from the center of the nebula thanks to pressure from radiation from the hot stars in its center."

Could there be Earth-sized free-floating planets out there?

"Most of the clouds in the Carina Nebula are less than the mass of Jupiter, so Earth-size planets can certainly be formed," Gahm told Universe Today, via Robert Cummings, communications officer from Chalmers. "I've thought that groups of three or four planets might form in the center, but only in the distant future will we be able to verify that idea."

The handful of rogue planets that have been detected were mainly found with microlensing, where the planet is found when it passes in front of a background star, temporarily making it look brighter. But Gahm said they will continue to look in the radio and also the millimeter/submillimeter regime to investigate the globulettes.

"We're almost done with an inventory of 220 globulettes in the Carina Nebula," he said. "We're finding that they're smaller and denser there than in all the other nebulae we've studied. Most likely they're further on in their development. In September we'll apply for time on ALMA, for the next step in trying to resolve their structure."

The team's paper, "

Mass and motion of globulettes in the Rosette Nebula

" has been published in the article in the July issue of the journal

Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Source:

Chalmers University of Technology

Universe Today

Universe Today