[/caption]

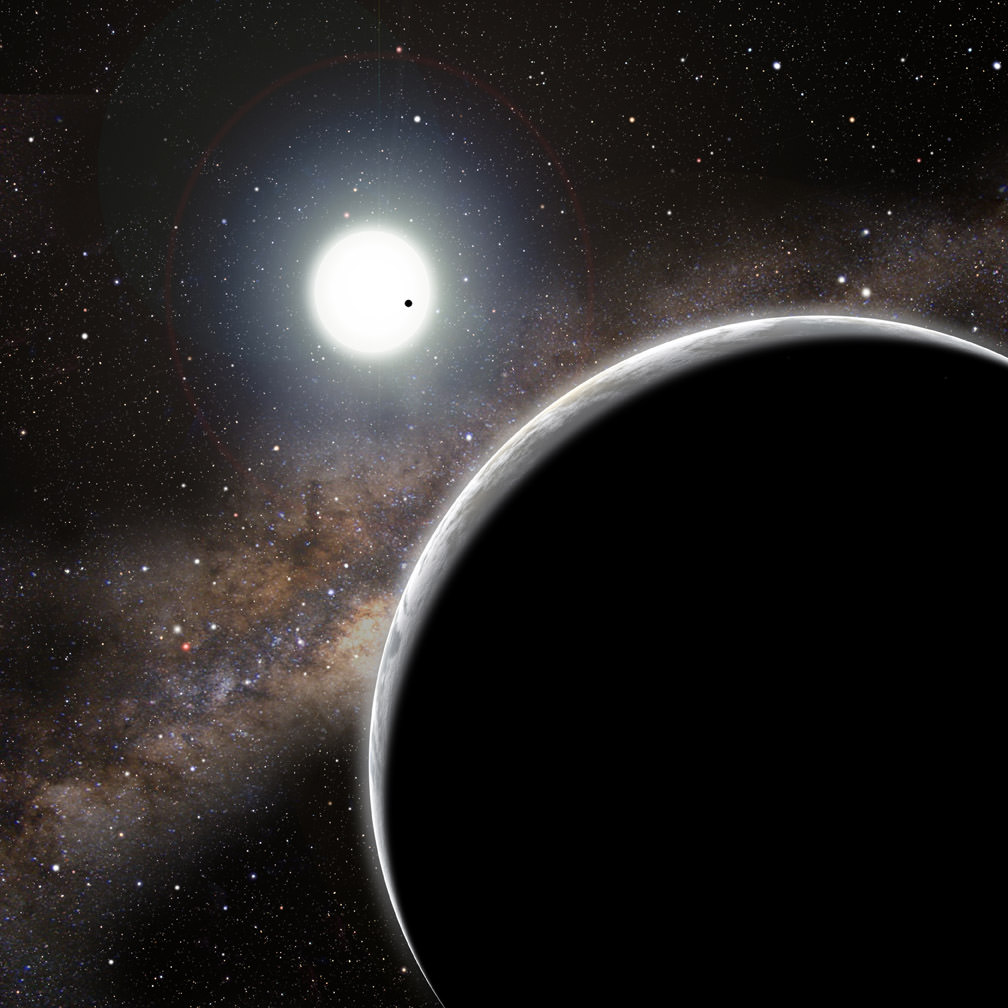

There's a planet out there playing a game of 'doorbell ditch' with astronomers. Scientists can't see this distant world, but they know it's there because its gravity is having a noticeable effect on the orbit of a neighboring planet.

"It's like having someone play a prank on you by ringing your doorbell and running away," said astronomer Sarah Ballard of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), lead author on a new paper published in the The Astrophysical Journal. "This invisible planet makes itself known by its influence on the planet we can see."

The planetary system of the visible and stealthy planets was discovered by the Kepler spacecraft, and the two worlds orbit a Sun-like star named Kepler-19. The system is located 650 light-years from Earth in the constellation Lyra. The 12th-magnitude star is well placed for viewing by backyard telescopes on September evenings in the northern hemisphere.

Launched in 2009, NASA's Kepler spacecraft hunts for extra-solar planets around stars other than our Sun by watching for planets orbiting in front of their stars. These "transiting" planets block some of the starlight, and that's how astronomers "see" that a planet is there.

However, the planet and star must line up exactly for us to see a transit.

That was the case for the first planet, Kepler-19b. It transits its star every 9 days and 7 hours, at a distance of 8.4 million miles from the star, where it is heated to a temperature of about 900 degrees Fahrenheit. The great thing about transits is that astronomers can deduce the planet's physical size: the greater the dip in light, the larger the planet relative to its star. Kepler-19b has a diameter of 18,000 miles, making it slightly more than twice the size of Earth. It may resemble a "mini-Neptune," however its mass and composition remain unknown.

If Kepler-19b were alone, each transit would follow the next like clockwork. Instead, the transits come up to five minutes early or five minutes late. Such transit timing variations show that another world's gravity is pulling on Kepler-19b, alternately speeding it up or slowing it down.

If this sounds somewhat familiar, the planet Neptune in our own solar system was discovered similarly. Astronomers tracking Uranus noticed that its orbit didn't match predictions. They realized that a more distant planet might be nudging or pulling on Uranus and calculated the expected location of the unseen world. Telescopes soon observed Neptune near its predicted position.

But this is the first time this method has been used to find a previously unknown planet in another solar system. Astronomers say no other current technique we have could have found the unseen companion.

"This method holds great promise for finding planets that can't be found otherwise," stated Harvard astronomer and co-author David Charbonneau.

So far, astronomers don't know anything about the invisible world Kepler-19c, other than that it exists. It weighs too little to gravitationally tug the star enough for them to measure its mass. And Kepler hasn't detected it transiting the star, suggesting that its orbit is tilted relative to Kepler-19b.

"Kepler-19c has multiple personalities consistent with our data. For instance, it could be a rocky planet on a circular 5-day orbit, or a gas-giant planet on an oblong 100-day orbit," said co-author Daniel Fabrycky of the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC).

The Kepler spacecraft will continue to monitor Kepler-19 throughout its mission. Those additional data will help nail down the orbit of Kepler-19c. Future ground-based instruments like HARPS-North will attempt to measure the mass of Kepler-19c. Only then will we have a clue to the nature of this invisible world.

Source:

Harvard Smithsonian CfA

Universe Today

Universe Today