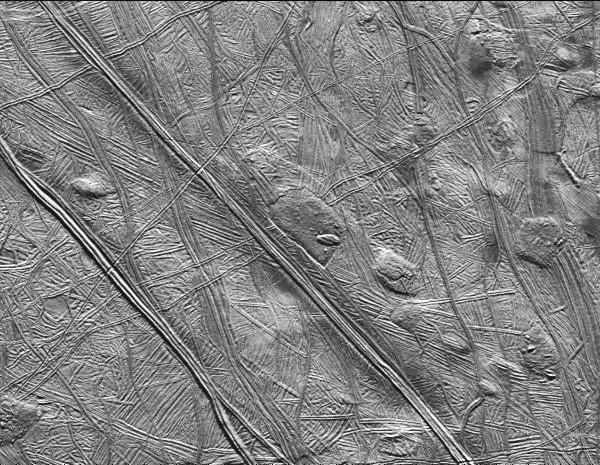

Europa is one of the four satellites of Jupiter that were discovered by Galileo over 400 years ago. It's slightly smaller than Earth's Moon and is covered by a thick shell of ice, beneath which lies a global subsurface ocean kept liquid by tidal heating from Jupiter's strong gravitational pull. Its surface is marked by cracks, ridges, and smooth plains, suggesting ongoing geological activity. There are features like domes and ridged terrains indicate that material from the interior may be interacting with the surface, possibly through processes like cryovolcanism.

.jpg) This is Europa in true colour from Juno's flyby (Credit : NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Kevin M. Gill)

This is Europa in true colour from Juno's flyby (Credit : NASA/JPL-Caltech/SwRI/MSSS/Kevin M. Gill)

The Galileo spacecraft's Solid State Imager revealed that Jupiter's moon Europa has a geologically young and diverse surface, Some of the domes, particularly those with circular or lobate shapes and smooth surfaces, are believed to be cryovolcanic in origin, formed by the eruption of water or slushy ice rather than molten rock. Various formation mechanisms have been proposed, including diapirism (upward movement of warmer ice) and cryovolcanic emplacement. Previous studies have identified 38 candidate cryolava domes in Europa's Conamara region, with a third modelled using a volume flux approach that suggested the erupted cryolava was far less viscous than previously estimated.

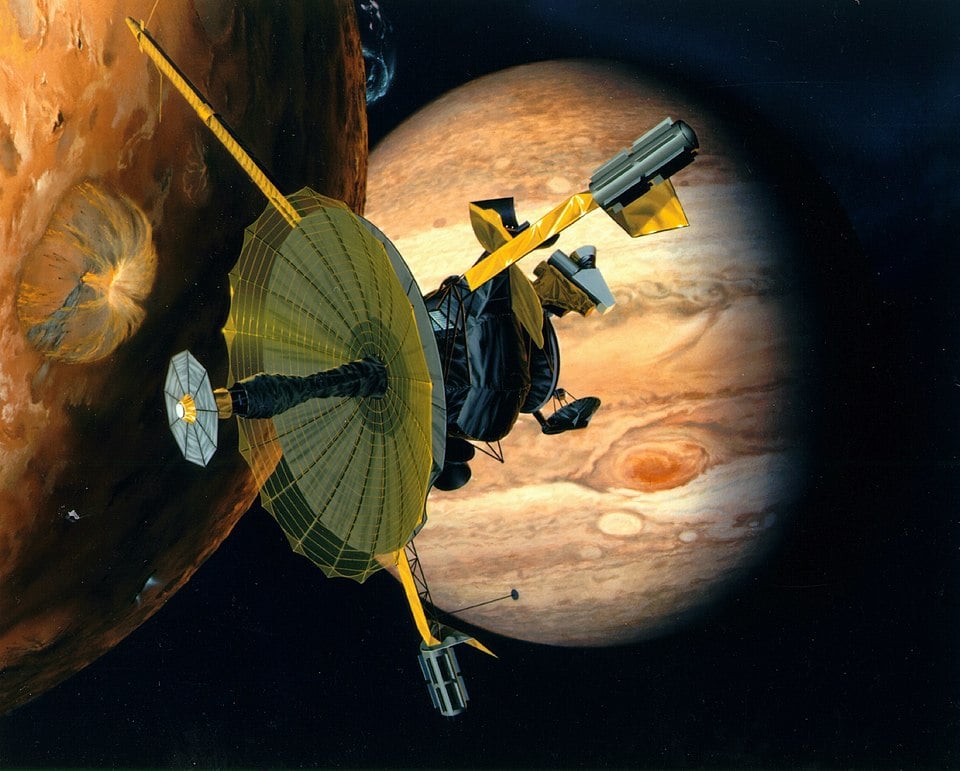

Artist's Image of NASA's Galileo Spacecraft Flying Past Jupiter's moon Io (Credit : NASA)

Artist's Image of NASA's Galileo Spacecraft Flying Past Jupiter's moon Io (Credit : NASA)

A recent piece of research led by Kierra A. Wilk from the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center has expanded the study to include 186 domes, providing deeper insight into the behaviour of Europa's cryolava and the potential for exchange between the surface and the subsurface ocean making it an environment that could be suitable for life. Using images and elevation data from Galileo's E6, E14, E15, and E17 flybys, the team identified and mapped potential cryovolcanic domes on Europa, noting their geological context, such as whether they intersect ridges, sit in depressions, or show signs of flow lobes.

For each dome, three topographic profiles were created with adjustments made for surrounding terrain to estimate relative dome heights. The average diameter and height of each dome were then used in models based on fluid dynamics to understand how they formed. While Earth's lava domes can take months to decades to form, Europa's cryolava domes are estimated to have formed in as little as one month to up to 50 years, depending on how quickly the cryolava cooled and solidified.

The new study uses the maximum dome height rather than the average based on previous studies, as using average height can underestimate cryolava viscosity by up to 100 times. The estimated formation time for the domes matches earlier studies, but viscosity may be higher if cooling and formation happened over the same period.

These findings suggest Europa's cryolava may behave like basaltic to andesitic lava on Earth and could be made of thick, particle-rich brine. Viscosity differences hint at varying temperatures or compositions in Europa's interior. Upcoming high-resolution data from the Europa Clipper mission will help identify more domes and active areas, offering deeper insight into Europa's geological activity and the potential habitability of its subsurface reservoirs.

Source :Mapping and Modelling of Candidate Cryovolcanic Domes on Europa

Universe Today

Universe Today