What is now a mountain, was once a lake. That's the conclusion of the Curiosity Mars rover science team after studying data and imagery from the rover, which indicates that the mountain the rover is now climbing in Gale Crater – Aeolis Mons, or Mount Sharp -- was built by sediments deposited in a large lake bed over tens of millions of years.

"Gale Crater had a large lake at the bottom -- perhaps even a series of lakes," said Michael Meyer, lead scientist for NASA's Mars Exploration Program during a press briefing on Monday, "that may have been big enough to last millions of years."

[caption id="attachment_117141" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

This evenly layered rock photographed by the Mast Camera (Mastcam) on NASA's Curiosity Mars Rover on Aug. 7, 2014, shows a pattern typical of a lake-floor sedimentary deposit not far from where flowing water entered a lake. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS. [/caption]

This isn't the first time that the Mars Science Laboratory team has made the conclusion that a lake once existed in Gale Crater, or even that the water was long-lived. A year ago,

the team said

that an ancient fresh water lake at the Yellowknife Bay area near Curiosity's landing site once existed for periods spanning perhaps millions to tens of millions of years in length – before eventually evaporating completely after Mars lost its thicker atmosphere.

But now, the team has garnered a bigger picture of Gale Crater, and they suggest that water could have covered nearly the entirety of the 154-kilometer-wide crater around 3.5 billion years ago, and that the 5-kilometer-high mountain that now towers over the crater could have been formed by repeated cycles of sediment buildup and erosion.

"If our hypothesis for Mount Sharp holds up, it challenges the notion that warm and wet conditions were transient, local, or only underground on Mars," said Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity deputy project scientist. "A more radical explanation is that Mars' ancient, thicker atmosphere raised temperatures above freezing globally, but so far we don't know how the atmosphere did that."

By continuing the study of this crater, Vasavada said, the team is "more sure than ever that we're going to learn about the early history of Mars, it's changing climate, and the potential for Mars to support life."

A few months ago, when Curiosity was still a few kilometers away from the base of Aeolis Mons, the science team started noticing distinct patterns on the rocks from images taken by the rover. There were tilted beds of sandstone all facing south in the direction of the mountain. The planetary geologists concluded that these tilted beds of sandstone formed where streams emptied into standing bodies of water, probably lakes.

[caption id="attachment_117167" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

This diagram depicts rivers feeding into a lake. Where the river enters the water body, the water's flow decelerates, sediments drop out, and a delta forms, depositing a prism of sediment that tapers out toward the lake's interior. Progressive build-out of the delta through time leads to formation of sediments that are inclined in the direction toward the lake body. Credit:

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS/Imperial College. [/caption]

Sediments carried by flowing water sink when they enter a body of water, forming a sloped wall that slowly advances forward as sediment continues to fall.

In September of this year, when Curiosity arrived at the rocks that form the base of Aeolis Mons at a region the team calls "Kimberley," they saw a new type of rock, one that forms when tiny particles of sediment slowly settle out within a lake, forming mud at the lake bottom. These 'mudstones' are very finely layered, suggesting that the river and lake system was going through cycles of change.

"Layered sandstone or pebble beds at the Kimberley record a build-out or accretion of sediment from north to south," said Curiosity science team member Sanjeev Gupta, " and that build-out of inclined beds strongly suggests rivers depositing sediment into a standing body of water."

[caption id="attachment_117166" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

This image from Curiosity's Mastcam shows inclined beds of sandstone interpreted as the deposits of small deltas fed by rivers flowing down from the Gale Crater rim and building out into a lake where Mount Sharp is now. It was taken March 13, 2014, just north of the "Kimberley" waypoint. Credit:

NASA/JPL-Caltech/MSSS[/caption]

Over a span of perhaps millions of years, water flowed from the northern rim of Gale Crater toward the center, bringing sediment that slowly formed the lower layers of Mount Sharp.

After the crater filled to a height of at least a few hundred yards and the sediments hardened into rock, the accumulated layers of sediment were sculpted over time into a mountainous shape by wind erosion that carved away the material between the crater perimeter and what is now the edge of the mountain.

While this is definitely not the first time that evidence of water has been discovered on Mars -- evidence from several Mars missions point to wet environments on ancient Mars – scientist have yet to put together a model of Mars' ancient climate that could have produced long periods warm enough for stable water on the surface.

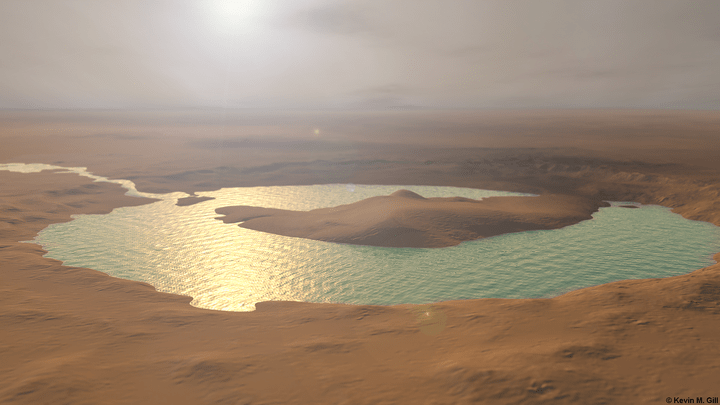

[caption id="attachment_117168" align="aligncenter" width="580"]

This illustration depicts a lake of water partially filling Mars' Gale Crater, receiving runoff from snow melting on the crater's northern rim.

Image Credit:

NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESA/DLR/FU Berlin/MSSS[/caption]

But this latest finding suggests Mars may have maintained a climate that could have produced long-lasting lakes at many locations on the Red Planet, which leads to potentially long-lasting habitable environments.

To learn more about this intriguing region on Mars, over the next few months the Curiosity rover will continue to climb up the lower layers of Aeolis Mons to see if the hypothesis for how it formed holds up. The team will also look at the chemistry of the rocks to see if the water that was once present would've been of the kind that could support microbial life.

"With only 30 vertical feet of the mountain behind us, we're sure there's a lot more to discover," said Vasavada.

Further reading:

NASA

Additional graphics from the press briefing.

Universe Today

Universe Today