[/caption]

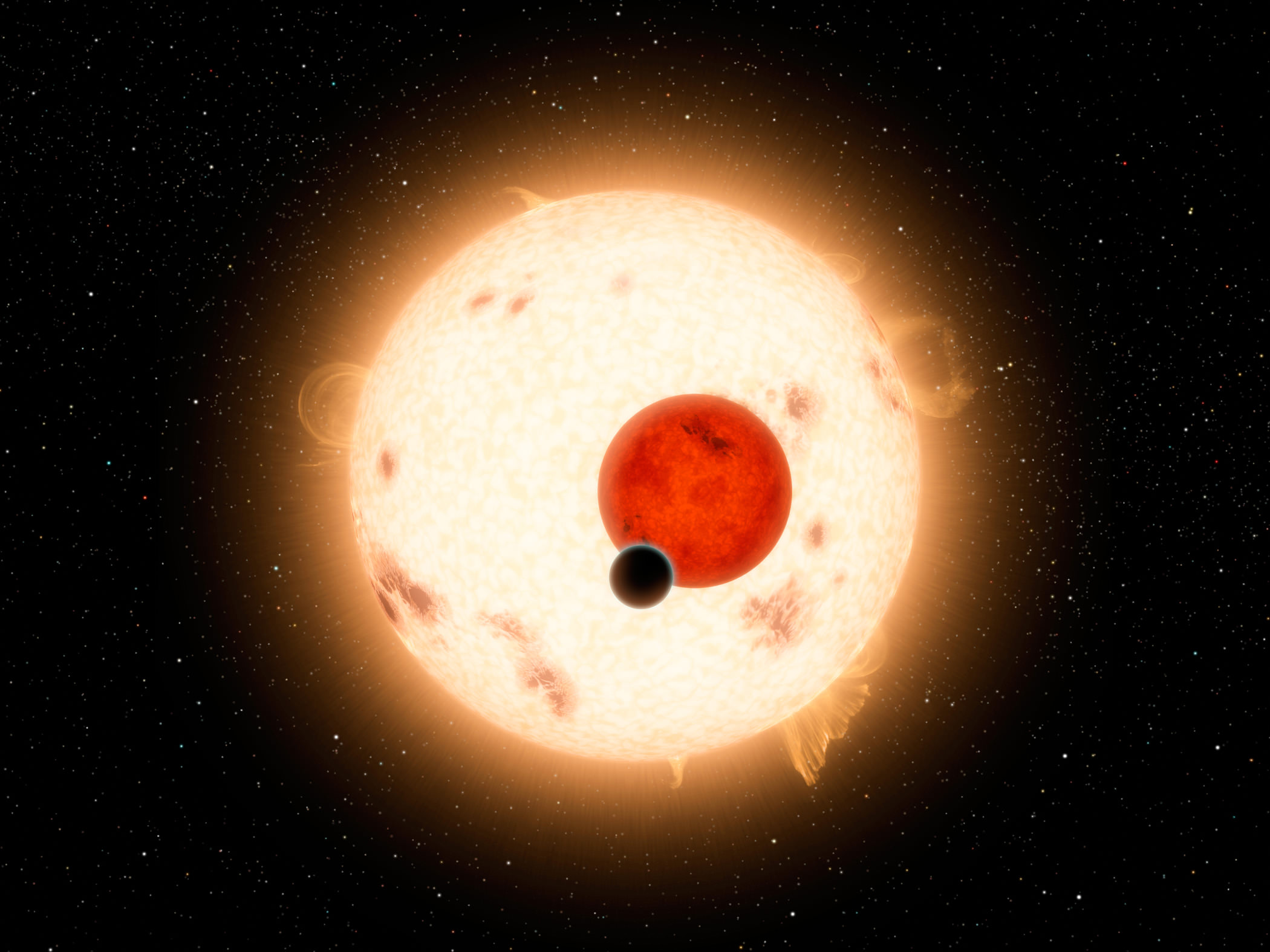

In a news conference today, Kepler mission scientists announced the first confirmed circumbinary planet ( a planet that orbits a binary star system). The planet in question, designated Kepler-16b has been compared to the planet Tatooine from the Star Wars saga.

Would it be possible for someone like Luke Skywalker to stand on the surface of Kepler-16b and see the famous “binary sunset” as depicted in Star Wars?

Despite the initial comparison between Kepler-16b and Tatooine, the planets really only have their orbit around a binary star system in common. Kepler-16b is estimated to weigh about a third the mass of Jupiter, with a radius of around three-quarters that of Jupiter.

Given the mass and radius estimates, this makes Kepler-16b closer to Saturn than the rocky, desert-like world of Tatooine. Kepler-16b’s orbit around its two parent stars takes about 229 days, which is similar to Venus’ 225-day orbit. At a distance of about 65 million miles from its parent stars, which are both cooler than our sun, temperatures on Kepler-16b are estimated in the range of around -100 C.

The team did mention that Kepler-16b is just outside of the habitable zone of the Kepler-16 system. Despite being just outside the habitable zone, the team did mention that it could be possible for Kepler-16b to have a habitable moon, if said moon had a thick, greenhouse gas atmosphere.

The Kepler mission detects exoplanet candidates by using the transit method which detects the dimming of the light emitted from a star as a planet crosses in front of it. In the case of Kepler-16b, the detection was complicated by the two stars in the system eclipsing each other.

The system’s brightness showed variations even when the stars were not eclipsing each other, which hinted at a third body. What further complicated matters was that the variations in brightness appeared at irregular time intervals. The irregular time intervals hinted that the stars were in different positions in their orbit each time the third body passed. After studying the data, the team came to the conclusion that the third body was orbiting, not just one, but both stars.

“Much of what we know about the sizes of stars comes from such eclipsing binary systems, and most of what we know about the size of planets comes from transits,” added Kepler scientist Laurance Doyle of the SETI Institute. “Kepler-16 combines the best of both worlds, with stellar eclipses and planetary transits in one system.” Doyle’s findings will be published in the Sept. 15th issue of the journal Science.

The Kepler mission is NASA’s first mission capable of finding Earth-size planets in or near the habitable zone – the region around a star where liquid water can exist on the surface of an orbiting planet. A considerable number of planets and planet candidates have been detected by the mission so far. If you’d like to learn more about the Kepler mission, visit: http://kepler.nasa.gov/

You can also read more about the Kepler-16b discovery at: http://kepler.nasa.gov/Mission/discoveries/kepler16b/

Source: NASA news conference / NASA TV

Ray Sanders is a Sci-Fi geek, astronomer and space/science blogger. Visit his website Dear Astronomer and follow on Twitter (@DearAstronomer) or Google+ for more space musings.

For those of you wondering what the two stars would look like from the planet, here is what I quickly calculated:

The larger of the two stars would appear as bright as the Sun does to us, but more orange in colour. It would appear to have roughly twice the angular radius of the Sun.

The smaller star would be very much fainter than the other, but still much brighter than the full Moon does to us. It would probably appear about the size of the Sun.

For those of you wondering what the two stars would look like from the planet, here is what I quickly calculated:

The larger of the two stars would appear as bright as the Sun does to us, but more orange in colour. It would appear to have roughly twice the angular radius of the Sun.

The smaller star would be very much fainter than the other, but still much brighter than the full Moon does to us. It would probably appear about the size of the Sun.

Interesting! Do we know how close to the large star the smaller star would appear to be in the sky?

The rumor (read somewhere today amongst a lot of Kepler articles) is Kepler has circumtrinary planets in the pipeline.

Unusual, I’m sure, but definitely not implausible. With what Kepler is finding now things are definitely going to get more interesting when newer space telescopes are flown (e.g., VLBA types).

Yes, First Super Jupiters, then Jupiter analogs, then Super Earths, next Earth analogs, and to come habitable Moons orbiting Exoplanets! I simply can’t wait for JWST(hopeful, based on information released yesterday) and as you say, newer Space telescopes and more sensitive spectral analysis.

Are there any estimates of the age of this system? I’m pleasantly surprised by these results – I didn’t think a binary star system like this could have a planetary system with stable orbits.

No, no age yet. But the first verified circumbinary, PSR B1620-26 b, is nicked “Methuselah”, since the neutron pulsar/white dwarf pair it orbits (at a safe 23 AU distance) is the oldest system yet, ~ 12.7 Ga old. Nearly as old as the universe, in other words.

It has also survived some interesting dynamics, see the link and its graphics.

This is but a part: “The origin of this pulsar planet is still uncertain, but it probably did not form where it is found today. Because of the decreased gravitational force when the core of star collapses to a neutron star and ejects most of its mass in a supernova explosion, it is unlikely that a planet could remain in orbit after such an event. It is more likely that the planet formed in orbit around the star that has now evolved into the white dwarf, and that the star and planet were only later captured into orbit around the neutron star.”

At capture, a putative original partner to the neutron star was presumably ejected. Or at least that is Wikipedia’s story, and they seem to stick to it!

Awesome! What a wonderful time to be alive! I can’t wait to see what other kinds of planets we discover.

I wonder if the smaller star could have been a super Jupiter, got too close to the primary, and ignited, any thoughts?

What you are saying i would compare to a match being held too close to a fire and igniting by the heat radiation of the fire.

Stars / brown dwarfs don’t work that way. They don’t burn by oxidising a fuel. They burn by nuclear fusion – in the core. This can only be ignited if the mass of the star is sufficient to create enough pressure in the core to heat it up to the necessary temperature – approx. 15 MK. So the red dwarf orbiting the main star most likely ignited by itself. If it formed in the orbit of the main star, nobody knows yet, i could well have been captured.

By the way, the red star will probably outlive the orange star by a good few billion years 🙂

I was thinking more along the line of gravity from the larger star might cause tidal forces in the interior of the smaller star, produce heat, and (maybe?) fusion. Sort of like Enceladus.

I seriously doubt it. Tidal forces would either completely disrupt a super Jupiter (if its too close, I’m thinking hill sphere sort of stuff but I’m not sure if its ever been observed since there are a lot of extrasolar planets that are very close to their star) or tidally lock it and maybe get boiled away. For ignition the central pressure and density are slightly more important than the temperature (it still needs to be very hot though) and I doubt being near a star would do anything to help raise them. If its not a star by the time it approaches the bigger star, its probably not going to be a star afterwards.

As an aside, according the NASA’s 16b discovery page, the separation (semi-major axis) of the pair is .22 AU with an eccentricity of .16 (not far off circular at 0). Unless something huge happened in the past to nearly circularise that orbit, it seems unlikely that the second star would ever get near enough to the primary for anything to happen to it… At least, that’s my thought about it anyway…

I seriously doubt it. Tidal forces would either completely disrupt a super Jupiter (if its too close, I’m thinking hill sphere sort of stuff but I’m not sure if its ever been observed since there are a lot of extrasolar planets that are very close to their star) or tidally lock it and maybe get boiled away. For ignition the central pressure and density are slightly more important than the temperature (it still needs to be very hot though) and I doubt being near a star would do anything to help raise them. If its not a star by the time it approaches the bigger star, its probably not going to be a star afterwards.

As an aside, according the NASA’s 16b discovery page, the separation (semi-major axis) of the pair is .22 AU with an eccentricity of .16 (not far off circular at 0). Unless something huge happened in the past to nearly circularise that orbit, it seems unlikely that the second star would ever get near enough to the primary for anything to happen to it… At least, that’s my thought about it anyway…

I seriously doubt it. Tidal forces would either completely disrupt a super Jupiter (if its too close, I’m thinking hill sphere sort of stuff but I’m not sure if its ever been observed since there are a lot of extrasolar planets that are very close to their star) or tidally lock it and maybe get boiled away. For ignition the central pressure and density are slightly more important than the temperature (it still needs to be very hot though) and I doubt being near a star would do anything to help raise them. If its not a star by the time it approaches the bigger star, its probably not going to be a star afterwards.

As an aside, according the NASA’s 16b discovery page, the separation (semi-major axis) of the pair is .22 AU with an eccentricity of .16 (not far off circular at 0). Unless something huge happened in the past to nearly circularise that orbit, it seems unlikely that the second star would ever get near enough to the primary for anything to happen to it… At least, that’s my thought about it anyway…

Many thanks to you and ‘info’ for answering my curiosity. Nice to have intelligent and polite responses.

The saturn sized planet could very well have a moon the size of Titan which is similar in size to Mercury. If it were habitable it would need either tidal heating to warm the planet via volcanism while producing a greenhouse atmosphere. This scenario is quite possible but it would be a stormy and cloudy moon with not much of a view of the sky. But what a spectacular sight the night sky would be there with a Saturn sized planet looming and two very different stars stars periodcially eclipsing each other. There would likely be other moons visible as well. This does shoot down some theories that had been brought up that planets could not form around this type of binary and if they did they would not stay in a stable orbit. The question now is whether these theories are null or whether they can still be applied to Earth-sized planets. I highly suspect that Earth sized plaents will also be found in stable orbits around this kind of binary system as well. I would also argue that they won’t be common to such systems, based on what we think we know about how exo-planetary systems form.

Would it necessarily be cloudy?

Well, since Jon Hanford hasn’t yet posted a link to the paper, I’ll do so:

Kepler-16: A Transiting Circumbinary Planet.

Ivan, thanks for the link! That paper was posted on Arxiv shortly after this post went up.

I wasn’t even sure there would be a stable solution to the orbit of a planet round a binary system – what shape would the orbit be? Any Maths experts out there able to enlighten us?

I beleive it would be eliptical, with one of the focal points being the centre of mass of the binary stars. I’m not very confident about that answer though – presumably there’s a lower limit to how small the orbit can be.

FWIW, Steinn Sigurdsson at Dynamic of Cats:

“This is the second circumbinary planet discovered, after 1620-26b and the first orbiting two main sequence stars.”

In the comments:

“I think next IAU conference may have the “planets are only around main sequence stars” issue surface, in conjunction with the refighting of the great “what is a planet” battle.

IAU already has a “an exoplanet is what we would call a planet in our solar system, but around another star” clause.

I almost wanna see astronomers explain to the public why the Earth will no longer be a planet when the Sun becomes a white dwarf?

And what about giants? Sub-giants?

We’ll need lots of popcorn.

And beer.”

Definitely beer. =D

FWIW, Steinn Sigurdsson at Dynamic of Cats:

“This is the second circumbinary planet discovered, after 1620-26b and the first orbiting two main sequence stars.”

In the comments:

“I think next IAU conference may have the “planets are only around main sequence stars” issue surface, in conjunction with the refighting of the great “what is a planet” battle.

IAU already has a “an exoplanet is what we would call a planet in our solar system, but around another star” clause.

I almost wanna see astronomers explain to the public why the Earth will no longer be a planet when the Sun becomes a white dwarf?

And what about giants? Sub-giants?

We’ll need lots of popcorn.

And beer.”

Definitely beer. =D

Best property Investment in India.

Property Investment in Chandigarh , Mullanpur new Chandigarh , Mohali Master Plan

For More Detail

+91-9501438259

http://www.landinmullanpur.com

http://www.property-in-mullanpur.yolasite.com

http://www.Chandigarhpropertyjunction.yolasite.com