On March 14, the ExoMars mission successfully lifted off on a 7-month journey to the planet Mars but not without a little surprise. The Breeze-M upper booster stage, designed to give the craft its final kick toward Mars, exploded shortly after parting from the probe. Thankfully, it wasn’t close enough to damage the spacecraft.

Michel Denis, ExoMars flight director at the European Space Operations, Center in Darmstadt, Germany, said that the two craft were many kilometers apart at the time of the breakup, so the explosion wouldn’t have posed a risk. Still, the mission team won’t be 100% certain until all the science instruments are completely checked over in the coming weeks.

All went well during the takeoff and final separation of the probe, but then something odd happened. Breeze-M was supposed to separate cleanly into two pieces — the main body and a detachable fuel tank — and maneuver itself to a graveyard or “junk” orbit, where rockets and spacecraft are placed at the end of their useful lives, so they don’t cause trouble with operational satellites.

But instead of two pieces, tracking photos taken at the OASI Observatory in Brazil not long after the stage and probe separated show a cloud of debris, suggesting an explosion occurred that shattered the booster to pieces. There’s more to consider. Space probes intended to either land or be crashed into planets have to pass through strict sterilization procedures that rocket boosters aren’t subject to. Assuming the Breeze-M shrapnel didn’t make it to its graveyard orbit, there exists the possibility some of it might be heading for Mars. If any earthly bugs inhabit the remains, it could potentially lead to unwanted consequences on Mars.

And this isn’t the first time a Russian Breeze-M has blown up.

According to Russian space observer Anatoly Zak in a recent article in Popular Mechanics, a Breeze-M that delivered a Russian spy satellite into orbit last December exploded on January 16. Propellant in one of its fuel tanks may not have been properly vented into space; heated by the sun, the tank’s contents likely combusted and ripped the stage apart. A similar incident occurred in October 2012.

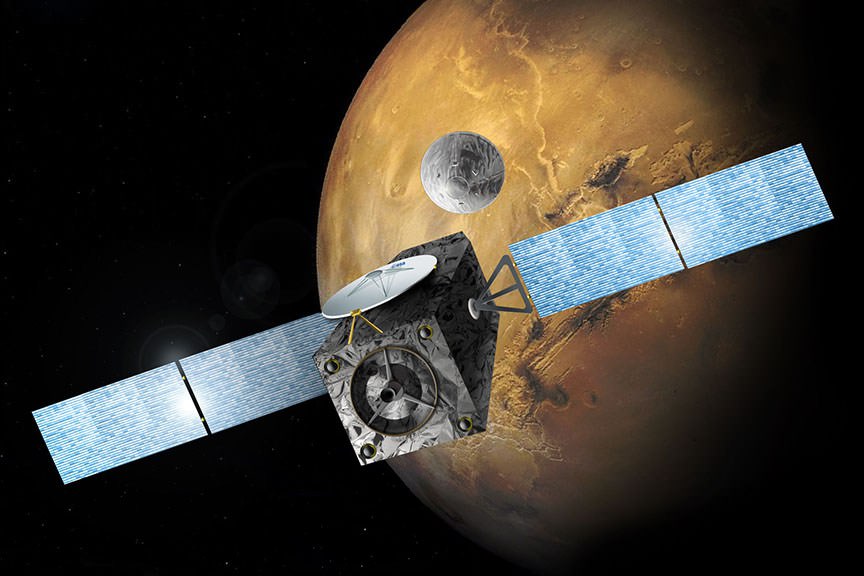

For now, we’ll embrace the good news that the spacecraft, which houses the Trace Gas Orbiter (TGO) and the Schiaparelli lander, are underway to Mars and in good health.

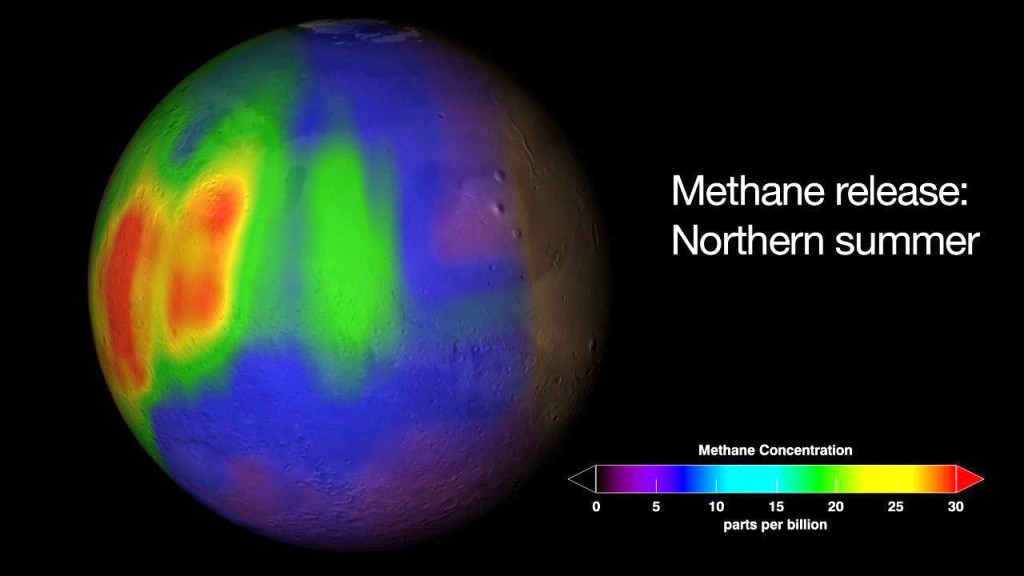

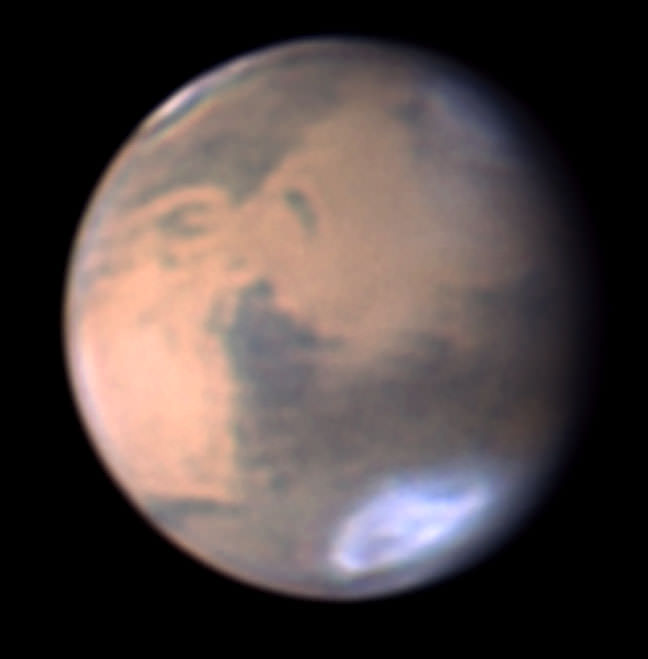

ExoMars is a joint venture between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Russian Federal Space Agency (Roscosmos). One of the mission’s key goals is to follow up on the methane detection made by ESA’s Mars Express probe in 2004 to understand where the gas comes from. Mars’ atmosphere is 95% carbon dioxide with the remaining 5% divided among nitrogen, argon, oxygen and others including small amounts of methane, a gas that on Earth is produced largely by living creatures.

Scientists want to know how martian methane got into the atmosphere. Was it produced by biology or geology? Methane, unless it is continuously produced by a source, only survives in the Martian atmosphere for a few hundreds of years because it quickly breaks down to form water and carbon dioxide. Something is refilling the atmosphere with methane but what?

TGO will also look at potential sources of other trace gases such as volcanoes and map the planet’s surface. It can also detect buried water-ice deposits, which, along with locations identified as sources of the trace gases, could influence the choice of landing sites of future missions.

The orbiter will also act as a data relay for the second ExoMars mission — a rover and stationary surface science platform scheduled for launch in May 2018 and arriving in early 2019.

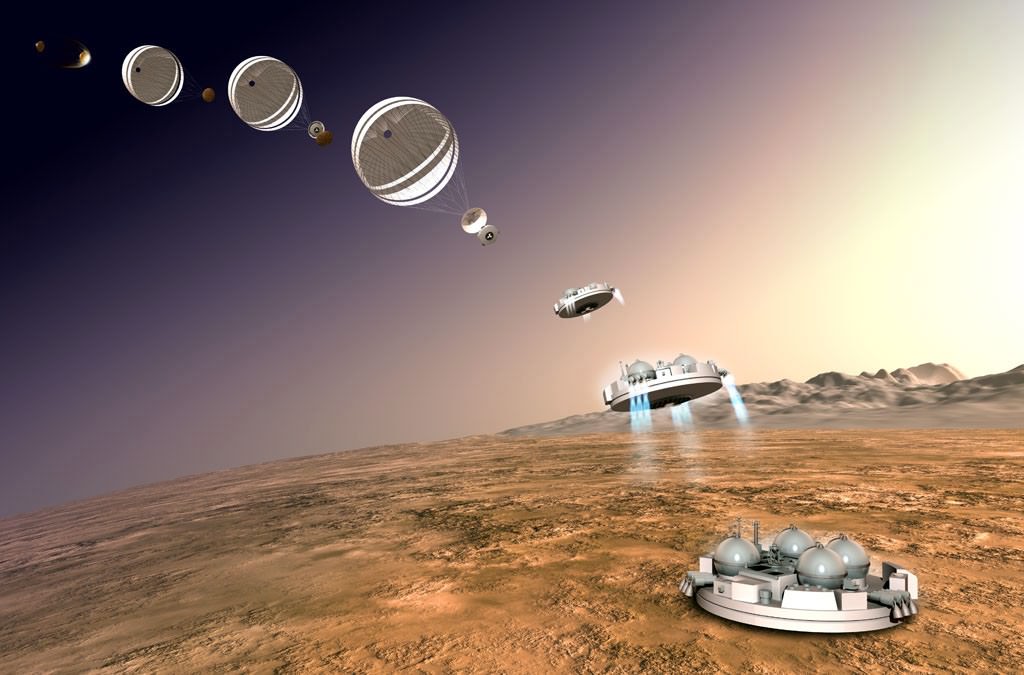

On October 16, when the spacecraft is still 559,000 miles (900,000 kilometers) from the Red Planet, the Schiaparelli lander will separate from the orbiter and three days later parachute down to the Martian surface. The orbiter will take measurements of the planet’s atmosphere (including methane) as well as any atmospheric electrical fields.

Mars is a popular place. There are currently five active orbiters there: two European (Mars Express and Mars Odyssey), two American (Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and MAVEN), one Indian (Mars Orbiter Mission) and two rovers (Opportunity and Curiosity) with another lander and orbiter en route!

You know, given all the problems the Russians have had with the Breeze-M stage, and the Proton rocket in general, one would think that they would be working harder on getting their new Angara launch vehicle up and running.

” … maneuver itself to a graveyard or “junk” orbit, where rockets and spacecraft are placed at the end of their useful lives, so they don’t cause trouble with operational satellites.”

Didn’t the Breeze-M achieve earth escape velocity and therefore be in solar orbit?

Man that was one close call for the mission. Guess the joke will be on the Russians now for mistakenly filling the booster with Vodka instead. All’s well that ends well…phew!