My, the Sun is a violent place. I mean, we knew that already, but there’s even more evidence for that using new data from a brand-new NASA spacecraft. There’s talk now about tornadoes and jets and even “bombs” swirling amid our Sun’s gassy environment.

A huge set of results from NASA’s Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) spacecraft reveals the true nature of a mysterious transition zone between Sun’s surface and the corona, or atmosphere. Besides the pretty fireworks and videos, these phenomena are telling scientists more about how the Sun moves energy from the center to the outskirts. And, it could tell us more about how stars work in general.

The results are published in five papers yesterday (Oct. 15) in Science magazine. Below, a brief glimpse of what each of these papers revealed about our closest star.

Bombs

This is a heck of a lot of energy packed in here. Raging at temperatures of 200,000 degrees Fahrenheit (111,093 degrees Celsius) are heat “pockets” — also called “bombs” because they release energy quickly. They were found lower in the atmosphere than expected. The paper is here (led by Hardi Peter of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research in Gottingen, Germany.)

Tornadoes

It’s a twist! You can see some structures in the chromosphere, just above the Sun’s surface, showing gas spinning like a tornado. They spin around as fast as 12 miles (19 kilometers) a second, which is considered slow-moving on the Sun. The paper is here (led by Bart De Pontieu, the IRIS science lead at Lockheed Martin in California).

High-speed jets

How does the solar wind — that constant stream of charged particles that sometimes cause aurora on Earth — come to be? IRIS spotted high-speed jets of material moving faster than ever observed, 90 miles (145 kilometers) a second. Since these jets are emerging in spots where the magnetic field is weaker (called coronal holes), scientists suspect this could be a source of the solar wind since the particles are thought to originate from there. The paper is here (led by Hui Tian at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Massachusetts.)

Nanoflares

Those solar flares the Sun throws off happen when magnetic field lines cross and then snap back into place, flinging particles into space. Nanoflares could do the same thing to heat up the corona, and that’s something else that IRIS is examining. The paper is here (led by Paola Testa, at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.)

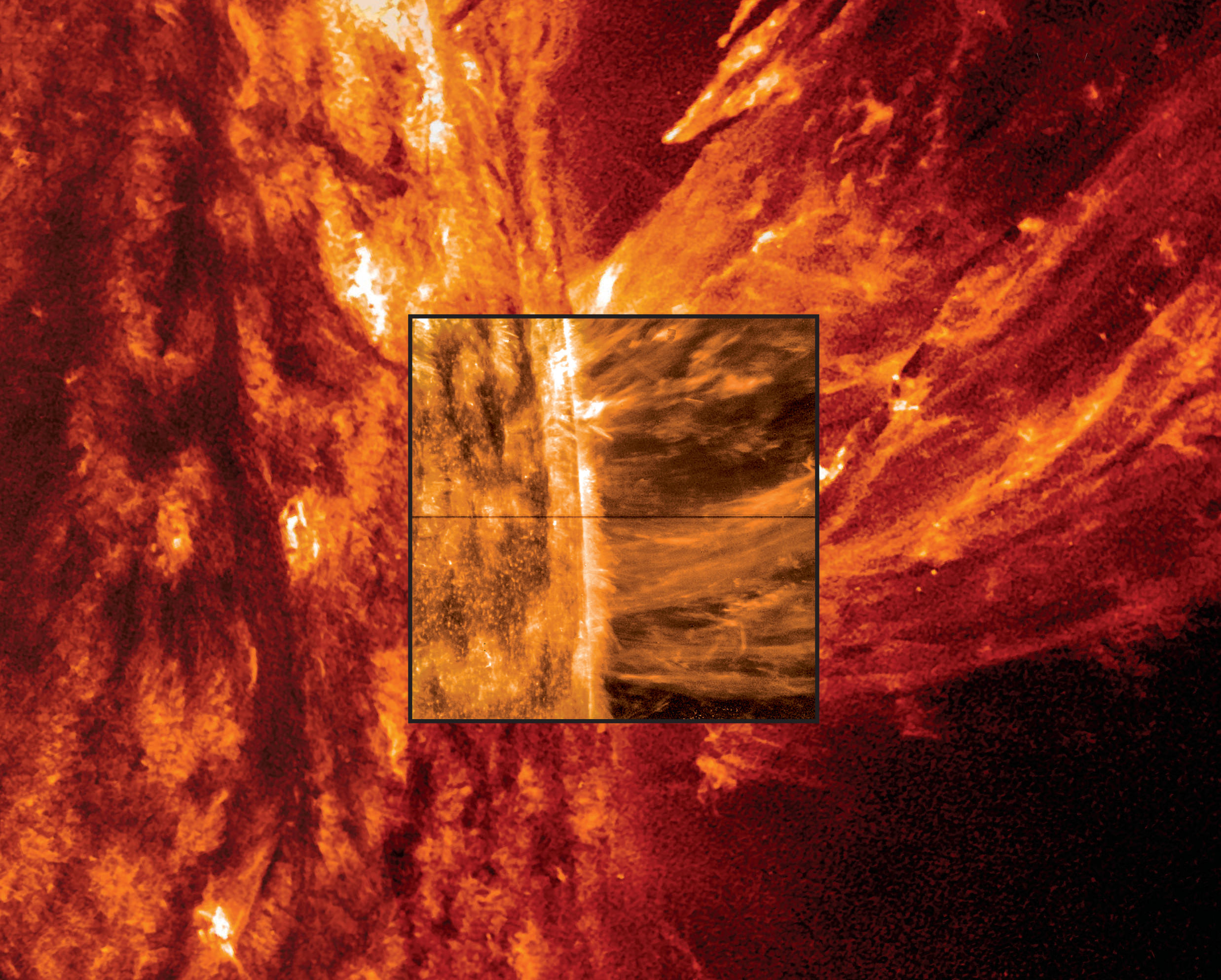

Structures and more

And here is the transition region in glorious high-definition. Improving on data from the Skylab space station in the 1970s (bottom of video), you can see all sorts of mini-structures on the Sun. The more we learn about these 2,000-mile (3,220-km) objects, the better we’ll understand how heating moves through the Sun. The paper is here (led by Viggo Hansteen, at the University of Oslo in Norway.)

Source: NASA