Looking for something off beat to observe? Some examples of curious astronomical objects lie within the reach of the dedicated amateur armed with a moderate-sized backyard telescope. With a little skill and persistence, you just might be able to track down a white dwarf star. Unlike splashy nebulae or globular clusters, a white dwarf star will just appear as a speck, a tiny dot in the field of view of your telescope’s eyepiece. But just as in the case of observing other exotic objects such as red giants and quasars, part of the thrill of tracking down these astrophysical beasties is in knowing just what it is that you’re seeing. Heck, many amateur astronomers fail to realize that any white dwarf stars are within range of their instruments and have never tracked one down.

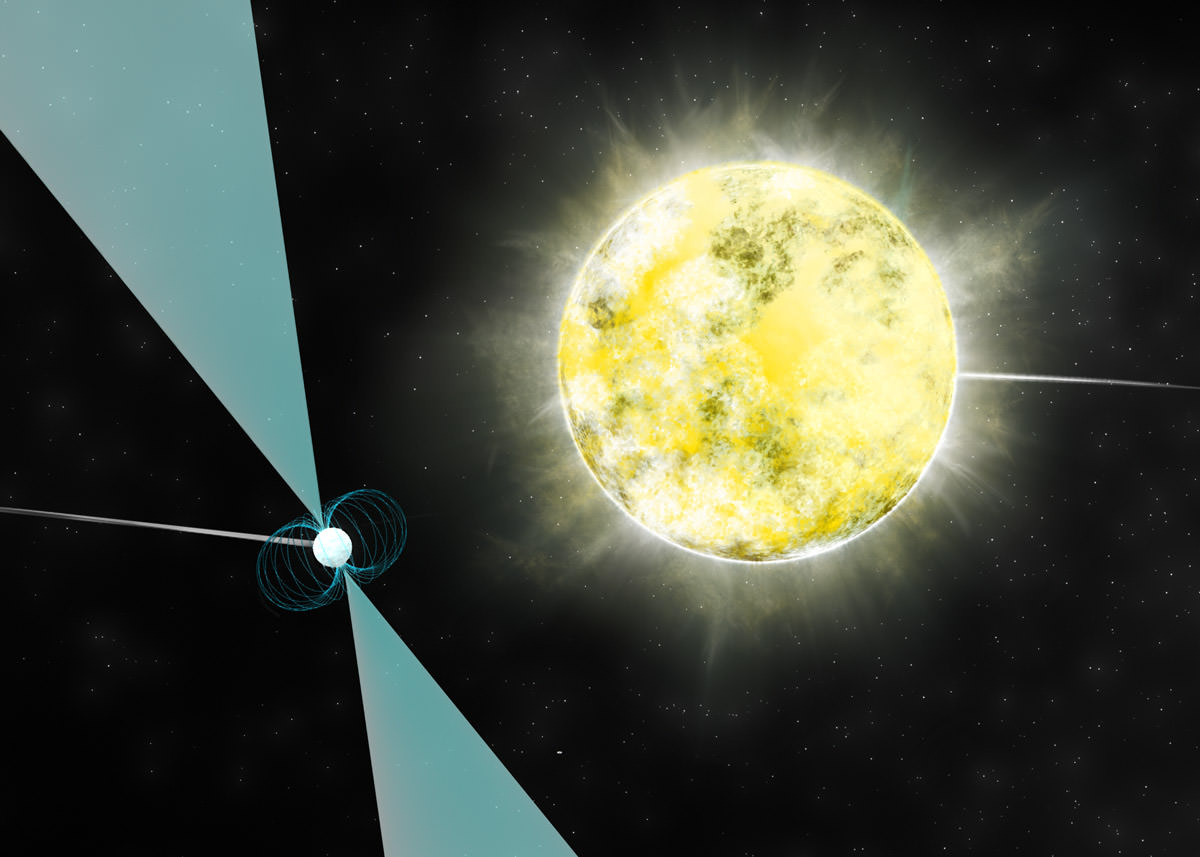

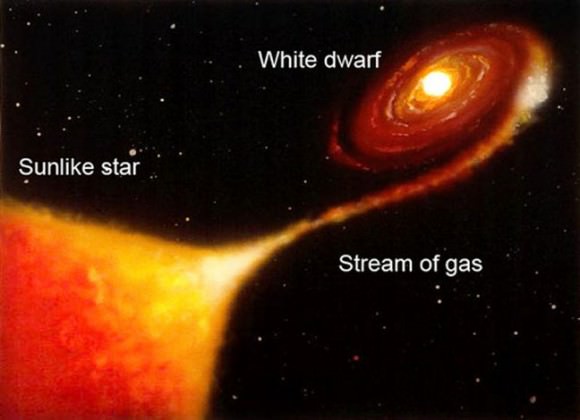

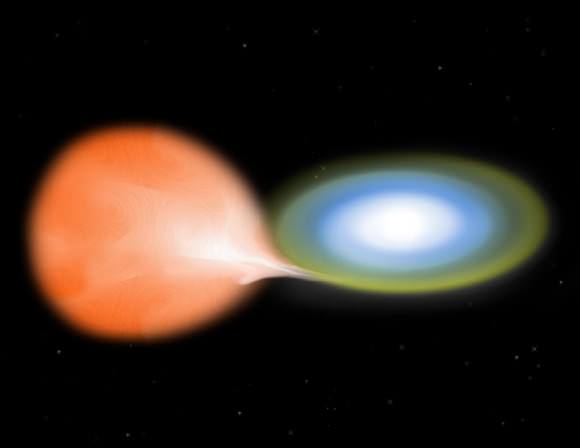

The astrophysical nature of white dwarf stars was first uncovered in the early 20th century. Most of the early white dwarf stars discovered were companions in binary star systems and this allowed astronomers to gauge their mass by following the orbital motion of such pairs over time. Soon, astronomers realized that they were looking at something peculiar, a new type of compact but massive stellar object that stubbornly refused to be pigeon-holed along the main sequence of the freshly conceived Hertzsprung-Russell diagram.

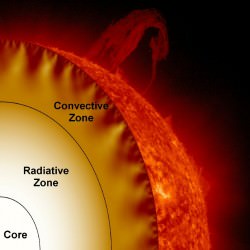

Today, we know that white dwarf stars are the remnants of stars which have long since passed the Red Giant stage. We say that a white dwarf is a degenerate star, and no, this not a commentary on its moral state. The Chandrasekhar limit gives us an upper limit in size for a white dwarf at about 1.4 solar masses, beyond which electron degeneracy pressure can no longer act against the inward pull of gravity. Our Sun will one day become a white dwarf, over 6 billion years from now. Think of cramming the mass of our star into the volume of the Earth and you have some idea just how dense a white dwarf is: a cubic centimetre of white dwarf weighs 250 about tons, and two cup fulls of white dwarf would weigh more than a Nimitz-class aircraft carrier.

Think of a white dwarf as a cooling ember of a star long past its hydrogen fusing prime. And white dwarfs will cool down to infrared radiating black dwarfs over trillions of years, far longer than the present 13.7 billion year age of the universe. In fact, the age of white dwarfs currently observed is one on the underpinning tenets of modern Big Bang cosmology.

All amazing stuff. In any event, here is a baker’s half dozen of white dwarf stars that you can find with a telescope tonight. A more extensive list of the nearest white dwarfs to the Earth can be found on Sol Station.

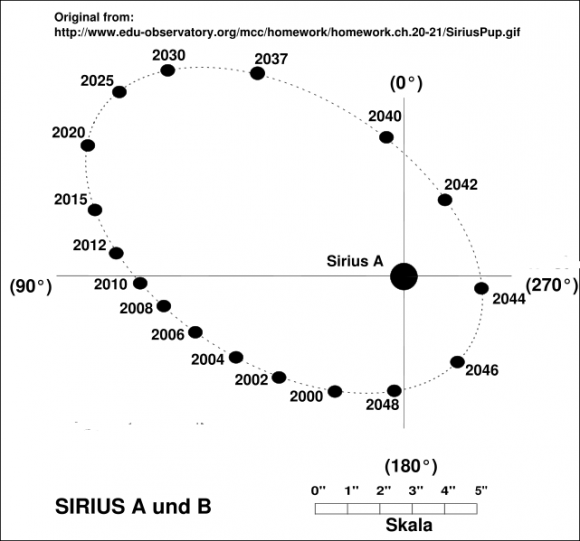

Sirius B: This is the nearest white dwarf to the Earth at 8.6 light years distant. Shining at magnitude +8.5, Sirius B would be a cinch to see, if only dazzling Sirius A — the brightest star in our sky at magnitude -1.5 — were not nearby. Sirius B orbits its primary once every 50 years and will reach a maximum separation of 11.5” from its primary in 2025, a prime time to cross it off of your life list in the coming decade. Blocking the primary just out of the field of view, or using an occulting bar eyepiece is key to finding Sirius B.

Sirius B was discovered by American telescope maker Alvan Graham Clark in 1862. The Dogon people of Mali also have some curious myths surrounding the star Sirius.

Constellation: Canis Major

Right Ascension: 6 Hours 45’

Declination: -16° 43’

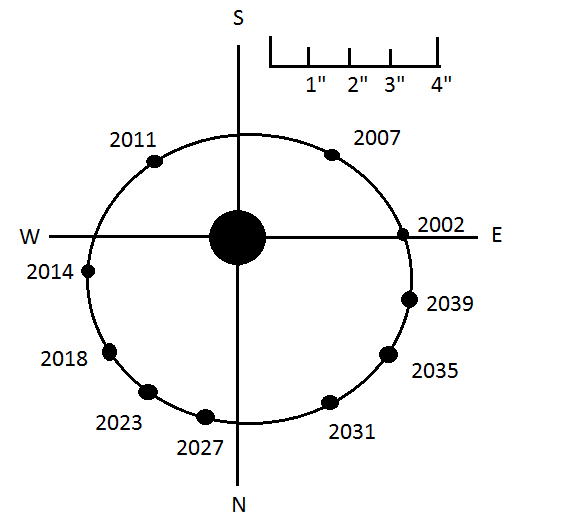

Procyon B: Located 11.5 light years distant, Procyon B was discovered in 1896 by John Martin Schaeberle from the Lick observatory. Shining at magnitude +10.7, the chief difficultly with spotting this white dwarf, as with Sirius B, is that it has a companion about 10 magnitudes – that’s 10,000 times brighter – nearby just 4.3” away.

Constellation: Canis Minor

Right Ascension: 7 hours 39’

Declination: +5 13’

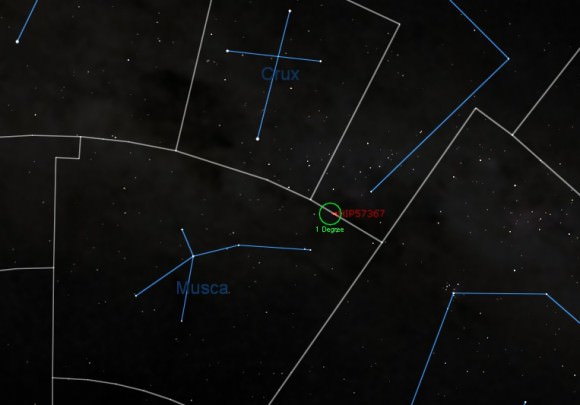

-LP145-141: Also known as GJ 440, LP145-141 is one of the best southern hemisphere white dwarf stars on the list. LP145-141 is a solitary white dwarf shining at magnitude +11.5. Located 15 light years distant, LP145-141 is thought to be a member of the nearby Wolf 219 Moving Group of stars.

Constellation: Musca

Right Ascension: 11 Hours 46’

Declination: -64° 50’

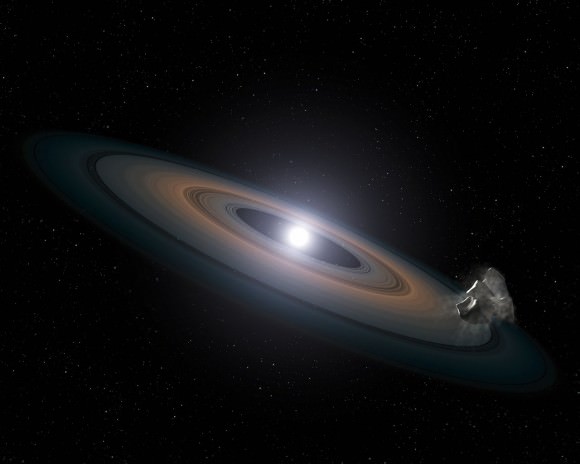

-Van Maanen’s Star: Shining at magnitude +12.4 and located 14.1 light years distant, Van Maanen’s star is the closest solitary white dwarf to Earth and the best example of a white dwarf for small telescopes. Discovered by Ariaan van Maanen in 1917, Van Maanen’s Star also has a very high proper motion of 3” per year.

Constellation: Pisces

Right Ascension: 00 Hours 49’

Declination: 05° 23’

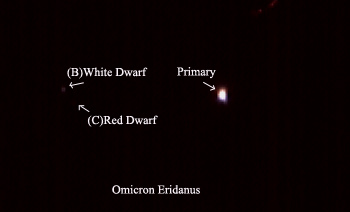

-40 Omicron Eridani B: This is a great one to track down. The triple system of 40 Omicron Eridani b contains a fine example of a red and white dwarf orbiting a main sequence star. Located 16.5 light years distant and shining at magnitude +9.5, Omicron Eridani was the first white dwarf star discovered in 1783 by Sir William Herschel, although its true nature wasn’t deduced until 1910. Omicron Eridani B is currently 82” from its primary, an easy split.

Constellation: Eridanus

Right Ascension: 4 Hours 15’

Declination: 7° 39’

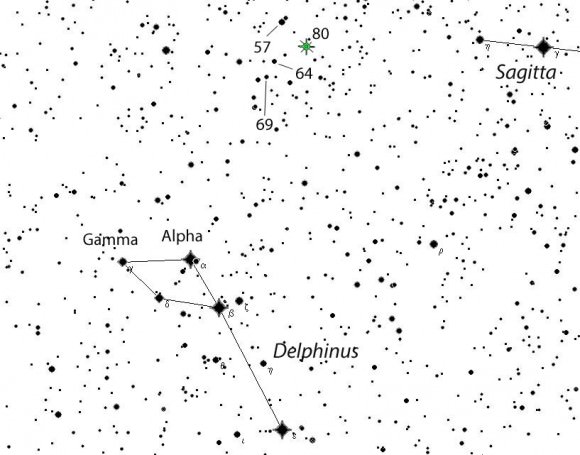

-Stein 2051: Rounding off the list and located just over 18 light years distant, Stein 2051 is another example of a red dwarf/white dwarf pair. Stein 2051 b shines at a similar brightest to Van Maanen’s star at magnitude +12.4.

Constellation: Camelopardalis

Right Ascension: 04 Hours 31’

Declination: +58° 59’

Let us know about your trials and triumphs in hunting down these fascinating objects!