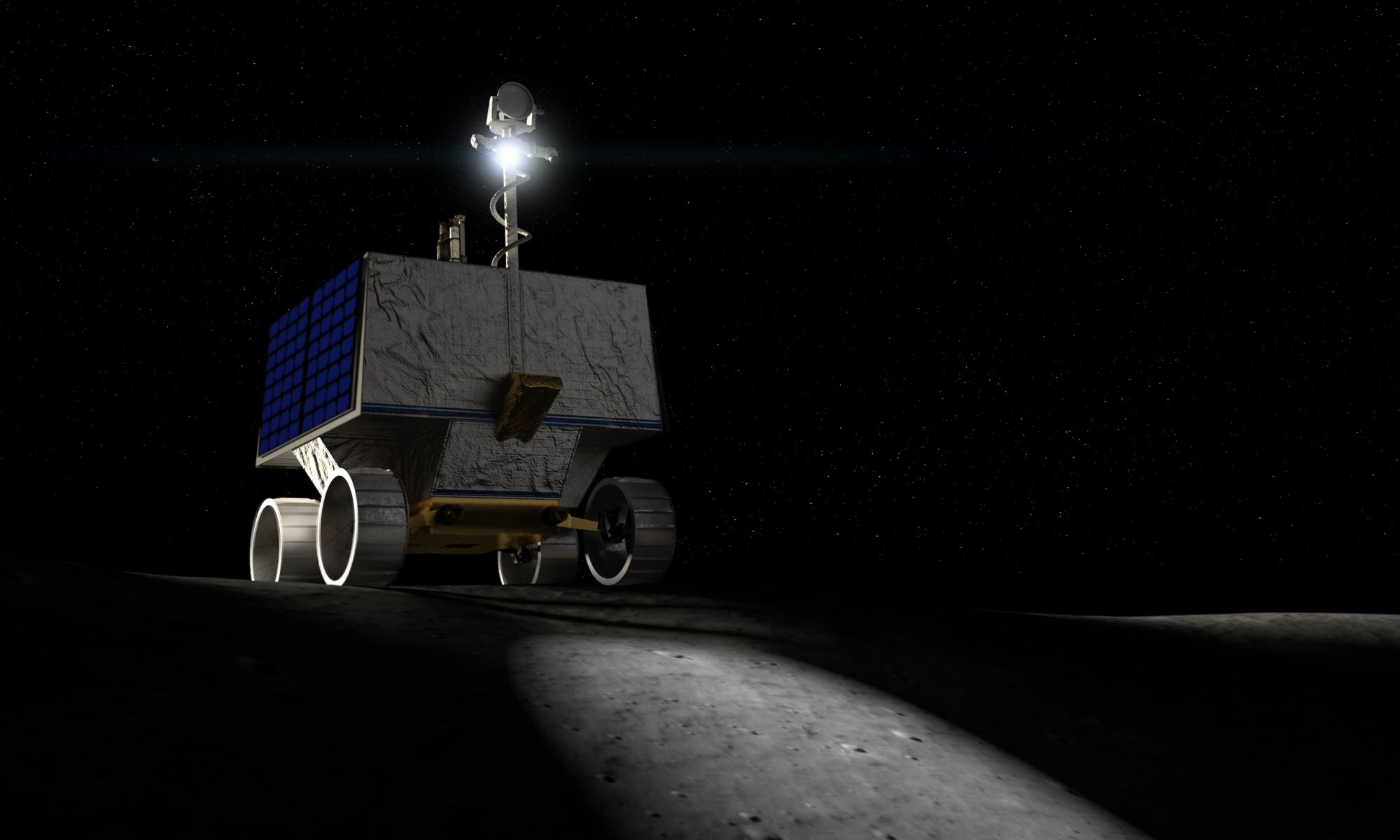

Meet VIPER, NASA’s new lunar rover, equipped with a drill to probe the Moon’s surface and look for water ice. VIPER, or Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover, will carry a one-meter drill and will use it to map out water resources at the Moon’s south pole. It’s scheduled to be on the lunar surface by December 2023, one year later than it’s initial date.

Continue reading “NASA is Planning to Build a Lunar Rover With a 1-Meter Drill to Search for Water Ice”China’s Yutu-2 Rover has now Traveled Over 345 Meters Across the Surface of the Moon

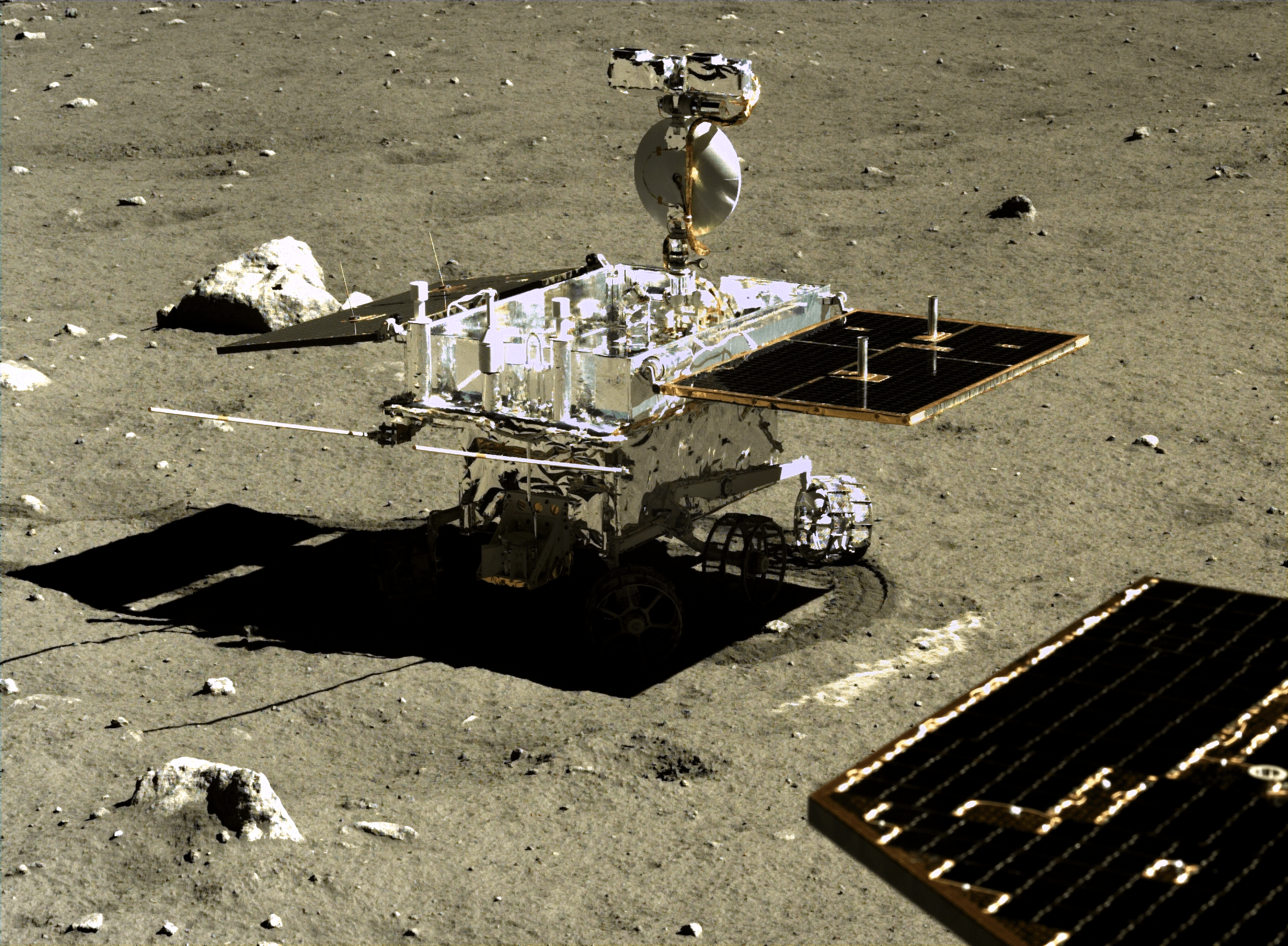

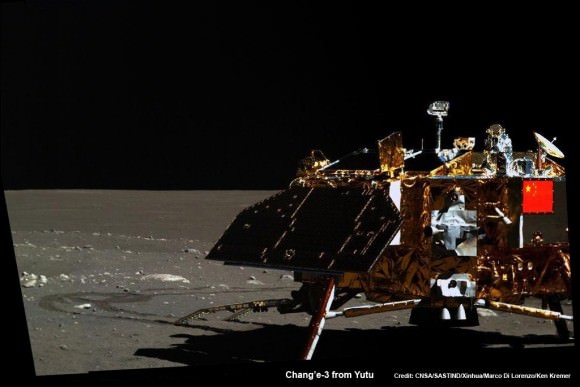

On January 3rd, 2019, China’s Chang’e-4 lander became the first mission in history to make a soft-landing on the far side of the Moon. After setting down in the Von Karman Crater in the South Pole-Aitken Basin, the rover element of the mission (Yutu 2) deployed and began exploring the lunar surface. In that time, the rover has traveled a total of 345.059 meters (377 yards) through previously unexplored territory.

Continue reading “China’s Yutu-2 Rover has now Traveled Over 345 Meters Across the Surface of the Moon”NASA is Testing a Rover That Could Search For Water Ice on The Moon

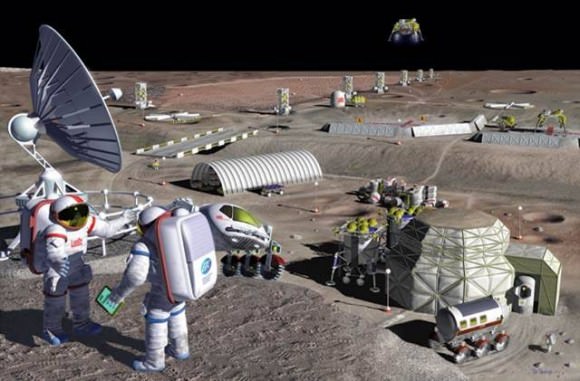

In the coming years, NASA will be sending astronauts back to the Moon for the first time since the last Apollo mission took place in 1972. Back in May, NASA announced that the plan – which is officially known as Project Artemis – was being expedited and would take place in the next five years. In accordance with the new timeline, Artemis will involve sending the first woman and next man to the Moon’s southern polar region by 2024.

To this end, NASA is working on a lunar rover that will search for and map out water deposits in the Moon’s southern polar region. It’s known as the Volatiles Investigating Polar Exploration Rover (VIPER) and it is scheduled to be delivered to the lunar surface by 2022. This mission will gather data that will help inform future missions to the South Pole-Aitken Basin and the eventual construction of a base there.

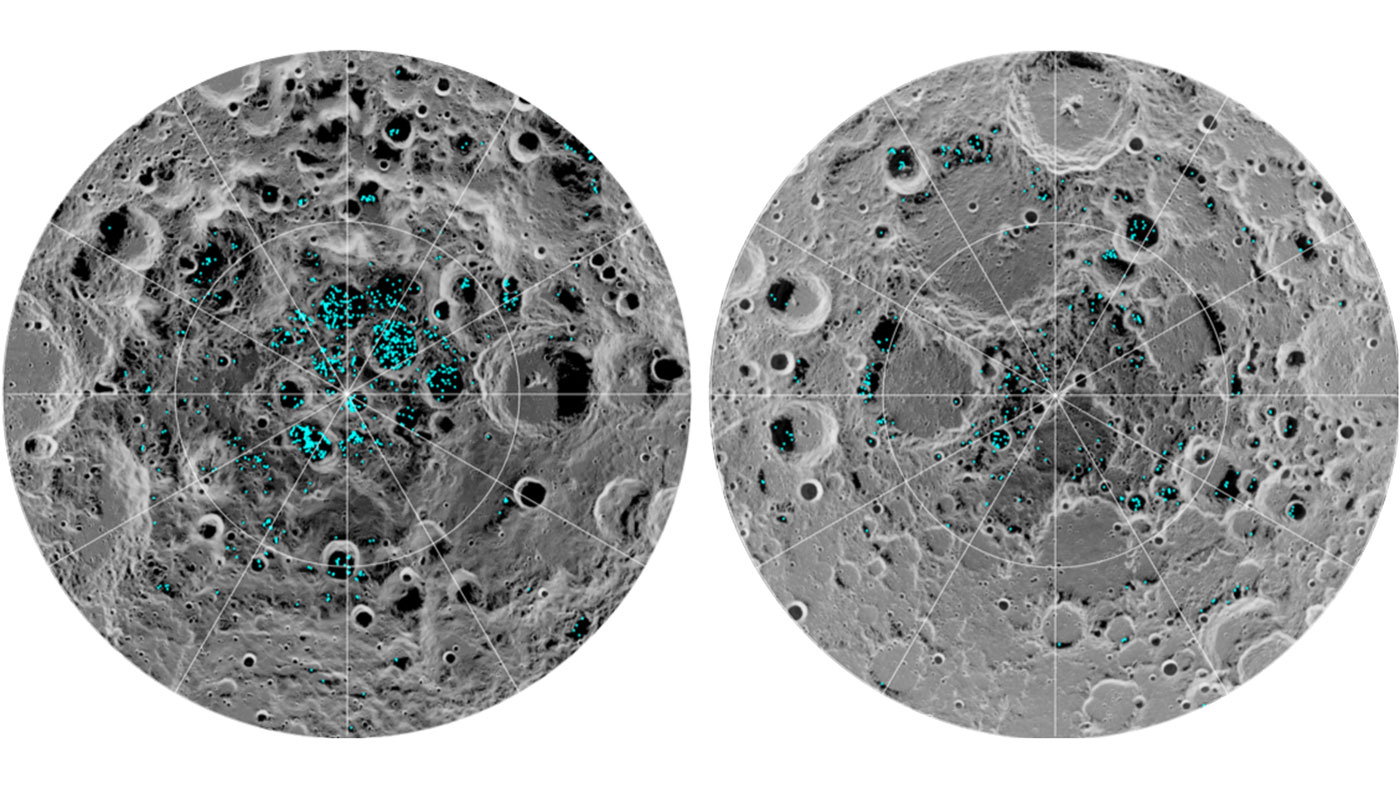

Continue reading “NASA is Testing a Rover That Could Search For Water Ice on The Moon”Dust off Your Lunar Colony Plans. There’s Definitely Ice at the Moon’s Poles.

When it comes right down to it, the Moon is a pretty hostile environment. It’s extremely cold, covered in electrostatically-charged dust that clings to everything (and could cause respiratory problems if inhaled), and its surface is constantly bombarded by radiation and the occasional meteor. And yet, the Moon also has a lot going for it as far as establishing a human presence there is concerned.

Continue reading “Dust off Your Lunar Colony Plans. There’s Definitely Ice at the Moon’s Poles.”

Was There a Time When the Moon was Habitable?

To put it simply, the Earth’s Moon is a dry, airless place where nothing lives. Aside from concentrations of ice that exist in permanently-shaded craters in the polar regions, the only water on the moon is believed to exist beneath the surface. What little atmosphere there is consists of elements released from the interior (some of which are radioactive) and helium-4 and neon, which are contributed by solar wind.

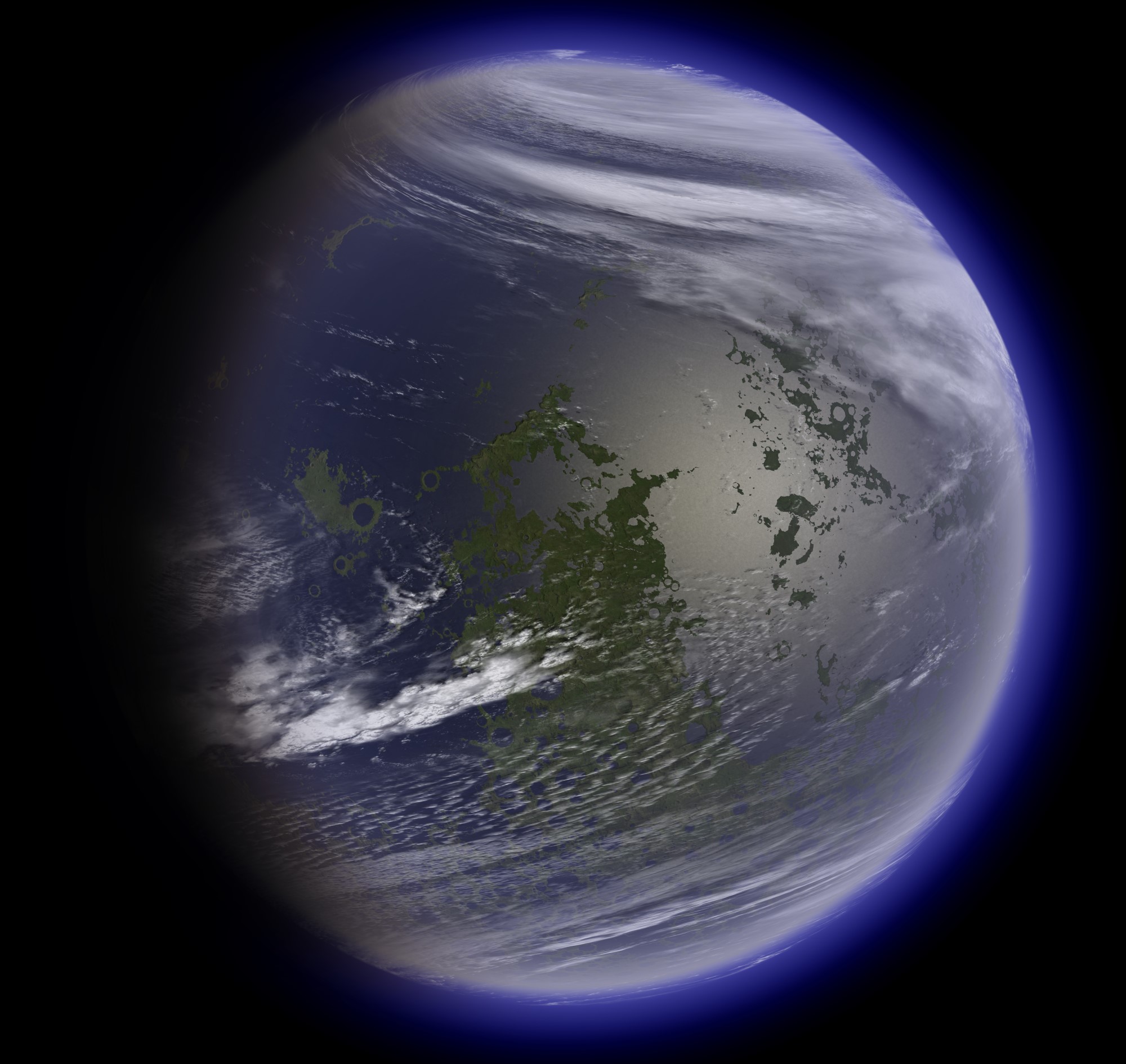

However, astronomers have theorized that there may have been a time when the Moon might have been inhabitable. According to a new study by an astrophysicist and an Earth and planetary scientist, the Moon may have had two early “windows” for habitability in the past. These took place roughly 4 billion years ago (after the Moon formed) and during the peak in lunar volcanic activity (ca. 3.5 billion years ago).

Continue reading “Was There a Time When the Moon was Habitable?”Study of Moon Rocks Suggest Interior of the Moon is Really Dry

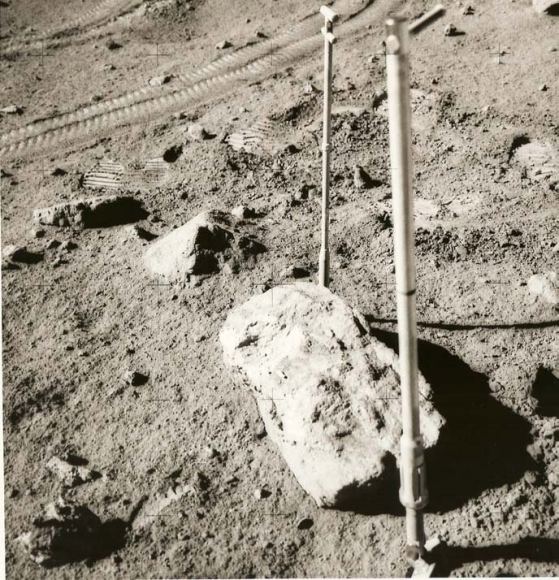

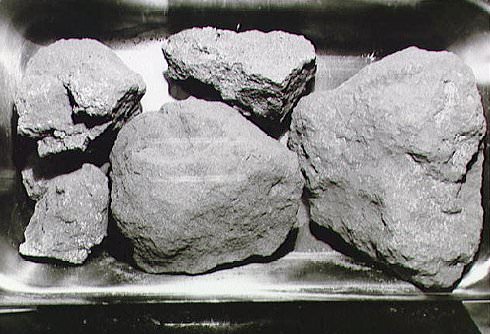

Long before the Apollo missions reached the Moon, Earth’s only satellites has been the focal point of intense interest and research. But thanks to the samples of lunar rock that were returned to Earth by the Apollo astronauts, scientists have been able to conduct numerous studies to learn more about the Moon’s formation and history. A key research goal has been determining how much volatile elements the Moon possesses.

Intrinsic to this is determining how much water the Moon possesses, and whether it has a “wet” interior. If the Moon does have abundant sources of water, it will make establishing outposts there someday much more feasible. However, according to a new study by an international team of researchers, the interior of the Moon is likely very dry, which they concluded after studying a series of “rusty” lunar rock samples collected by the Apollo 16 mission.

The study, titled “Late-Stage Magmatic Outgassing from a Volatile-Depleted Moon“, appeared recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Led by James M. D. Day of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, the team’s research was funded by the NASA Emerging Worlds program – which finances research into the Solar System’s formation and early evolution.

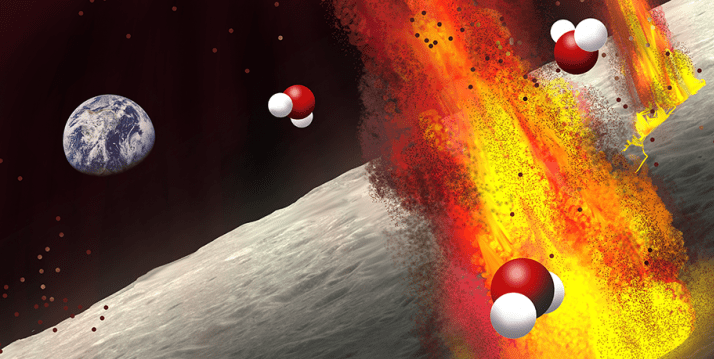

Determining how rich the Moon is in terms of volatile elements and compounds – such as zinc, potassium, chlorine, and water – is important because it provides insight into how the Moon and Earth formed and evolved. The most-widely accepted theory is that Moon is the result of “catastrophic formation”, where a Mars-sized object (named Theia) collided with Earth about 4.5 billion years ago.

The debris kicked up by this impact eventually coalesced to form the Moon, which then moved away from Earth to assume its current orbit. In accordance with this theory, the Moon’s surface would have been an ocean of magma during its early history. As a result, volatile elements and compounds within the Moon’s mantle would have been depleted, much in the same way that the Earth’s upper mantle is depleted of these elements.

As Dr. Day explained in a Scripps Institution press statement:

“It’s been a big question whether the moon is wet or dry. It might seem like a trivial thing, but this is actually quite important. If the moon is dry – like we’ve thought for about the last 45 years, since the Apollo missions – it would be consistent with the formation of the Moon in some sort of cataclysmic impact event that formed it.”

For the sake of their study, the team examined a lunar rock named “Rusty Rock 66095” to determine the volatile content of the Moon’s interior. These rocks have mystified scientists since they were first brought back by the Apollo 16 mission in 1972. Water is an essential ingredient to rust, which led scientists to conclude that the Moon must have an indigenous source of water – something which seemed unlikely, given the Moon’s extremely tenuous atmosphere.

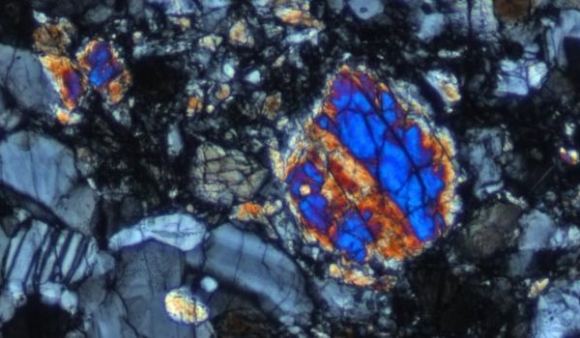

Using a new chemical analysis, Day and his colleagues determined the levels of istopically light zinc (Zn66) and heavy chlorine (Cl37), as well as the levels of heavy metals (uranium and lead) in the rock. Zinc was the key element here, since it is a volatile element that would have behaved somewhat like water under the extremely hot conditions that were present during the Moon’s formation.

Ultimately, the supply of volatiles and heavy metals in the sample support the theory that volatile enrichment of the lunar surface occurred as a result of vapor condensation. In other words, when the Moon’s surface was still an ocean of hot magma, its volatiles evaporated and escaped from the interior. Some of these then condensed and were deposited back on the surface as it cooled and solidified.

This would explain the volatile-rich nature of some rocks on the lunar surface, as well as the levels of light zinc in both the Rusty Rock samples and the previously-studied volcanic glass beads. Basically, both were enriched by water and other volatiles thanks to extreme outgassing from the Moon’s interior. However, these same conditions meant that most of the water in the Moon’s mantle would have evaporated and been lost to space.

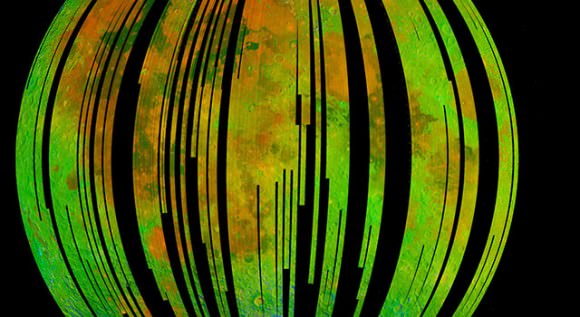

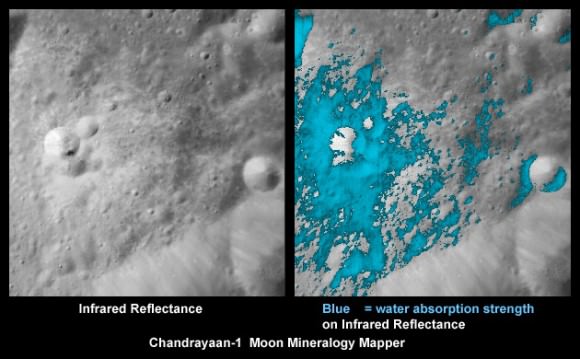

Image credit: ISRO/NASA/JPL-Caltech/Brown Univ./USGS

This represents something of a paradox, in that it shows how rocks that contain water were formed in a very dry, interior part of the Moon. However, as Day indicated, it offers a sound explanation for an enduring lunar mystery:

“I think the Rusty Rock was seen for a long time as kind of this weird curiosity, but in reality, it’s telling us something very important about the interior of the moon. These rocks are the gifts that keep on giving because every time you use a new technique, these old rocks that were collected by Buzz Aldrin, Neil Armstrong, Charlie Duke, John Young, and the Apollo astronaut pioneers, you get these wonderful insights.”

These results contradict other studies that suggest the Moon’s interior is wet, one of which was recently conducted by researchers at Brown University. By combining data provided by Chandrayaan-1 and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) with new thermal profiles, the Brown research team concluded that lots of water exists within volcanic deposits on the Moon’s surface, which could also mean there are vast quantities of water in the Moon’s interior.

To these, Day emphasized that while these studies present evidence that water exists on the lunar surface, they have yet to offer a solid explanation for what mechanisms deposited it on the surface. Day and his colleague’s study also flies in the face of other recent studies, which claim that the Moon’s water came from an external source – either by comets which deposited it, or from Earth during the formation of the Earth-Moon system.

Those who believe that lunar water was deposited by comets cite the similarities between the ratios of hydrogen to deuterium (aka. “heavy hydrogen”) in both the Apollo lunar rock samples and known comets. Those who believe the Moon’s water came from Earth, on the other hand, point to the similarity between water isotopes on both the Moon and Earth.

In the end, future research is needed to confirm where all of the Moon’s water came from, and whether or not it exists within the Moon’s interior. Towards this end, one of Day’s PhD students – Carrie McIntosh – is conducting her own research into the lunar glass beads and the composition of the deposits. These and other research studies ought to settle the debate soon enough!

And not a moment too soon, considering that multiple space agencies hope to build a lunar outpost in the upcoming decades. If they hope to have a steady supply of water for creating hydrazene (rocket fuel) and growing plants, they’ll need to know if and where it can be found!

Further Reading: UC San Diego, PNAS

Good News for Future Moon Bases. There’s Water Inside the Moon

Since the Apollo program wrapped up in the early 1970s, people all around the world have dreamed of the day when we might return to the Moon, and stay there. And in recent years, however, that actual proposals for a lunar settlement have begun to take shape. As a result, a great deal of attention and research has been focused on whether or not the Moon has indigenous sources of water.

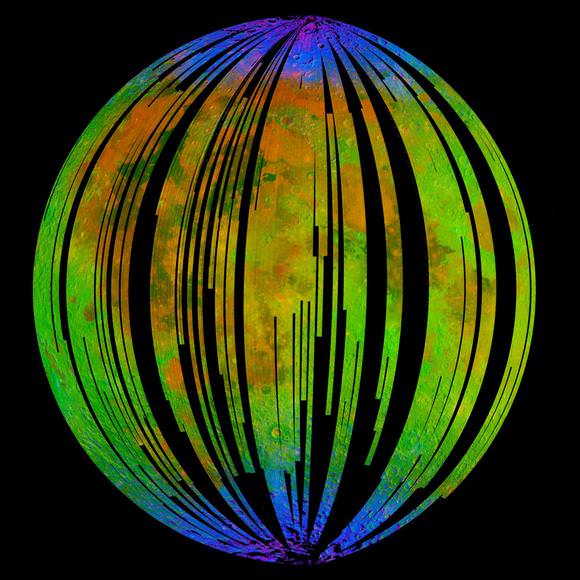

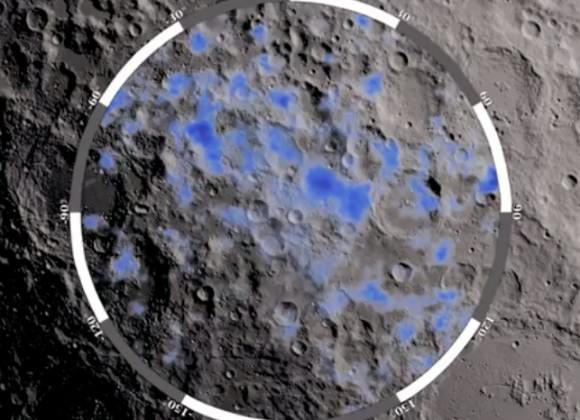

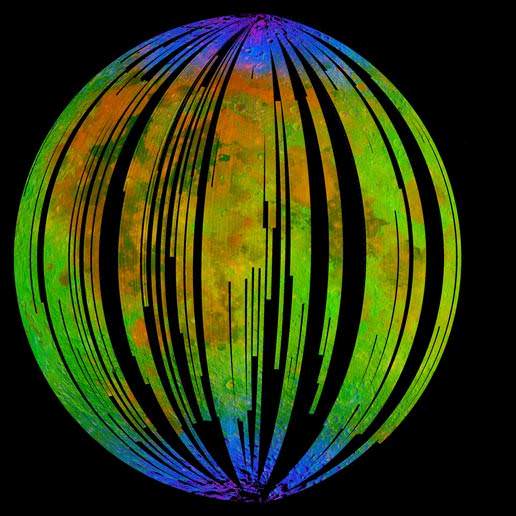

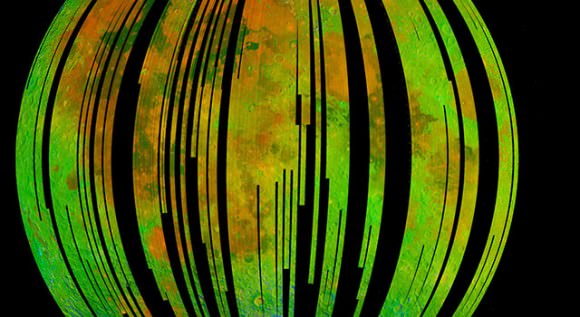

Thanks to missions like Chandrayaan-1 and the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), scientists know that there are vast amounts of surface ice on the Moon. However, according to a new study, researchers from Brown University have found evidence of widespread water within volcanic deposits on the lunar surface. These findings could indicate that there are also vast sources of water within the Moon’s interior.

For their study – titled “Remote Detection of Widespread Indigenous Water in Lunar Pyroclastic Deposits” – Brown researchers Ralph E. Milliken and Shuai Li combined satellite data with new thermal profiles to search for signs of water away from the polar regions. In so doing, they addressed a long-standing theory about the likelihood of water in the Moon’s interior, as well as the predominant theory of how the Moon formed.

As noted, scientists have known for years that there are large amounts of frozen water in the Moon’s polar regions. At the same time, however, scientists have held that the Moon’s interior must have depleted of water and other volatile compounds billions of years ago. This was based on the widely-accepted hypothesis that the Moon formed after a Mars-sized object (named Theia) collided with Earth and threw up a considerable amount of debris.

Essentially, scientists believed that it was unlikely that any hydrogen – necessary to form water – could have survived the heat of this impact. However, as of a decade ago, new scientific findings began to emerge that cast doubt on this. The first was a 2008 study, where a team of researches (led by Alberto Saal of Brown University) detected trace amounts of water in samples of volcanic glass that were bought back by the Apollo 15 and Apollo 17 missions.

This was followed by a 2011 study (also from Brown University) that indicated how crystalline structures within those beads contained as much water as some basalt mineral deposits here on Earth. These findings were particularly significant, in that they suggested that parts of the Moon’s mantle could contain as much water as Earth’s. The question though was whether these findings represented the norm, or an anomaly.

As Milliken, an associate professor in Brown’s Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences (DEEPS) and the co-author on the paper, summarized in a recent Brown press release:

“The key question is whether those Apollo samples represent the bulk conditions of the lunar interior or instead represent unusual or perhaps anomalous water-rich regions within an otherwise ‘dry’ mantle. By looking at the orbital data, we can examine the large pyroclastic deposits on the Moon that were never sampled by the Apollo or Luna missions. The fact that nearly all of them exhibit signatures of water suggests that the Apollo samples are not anomalous, so it may be that the bulk interior of the Moon is wet.”

To resolve this, Milliken and Li consulted orbital data to examine lunar volcanic deposits for signs of water. Basically, orbiters use spectrometers to bounce light off the surfaces of planets and astronomical bodies to see which wavelengths of light are absorbed and which are reflected. This data is therefore able to determine what compounds and minerals are present based on the absorption lines detected.

Using this technique to look for signs of water in lunar volcanic deposits (aka. pyroclastic deposits), however, was a rather difficult task. During the day, the lunar surface heats up, especially in the latitudes where volcanic deposits are located. As Milliken explained, spectronomers will therefore pick up thermal energy in addition to chemical signatures which this can throw off the readings:

“That thermally emitted radiation happens at the same wavelengths that we need to use to look for water. So in order to say with any confidence that water is present, we first need to account for and remove the thermally emitted component.”

To correct for this, Milliken and Li constructed a detailed temperature profile of the areas of the Moon they were examining. They then examined surface data collected by the Moon Mineralogy Mapper, the spectrographic imager that was part of India’s Chandrayaan-1 mission. They then compared this thermally-corrected surface data to the measurements conducted on the samples returned from the Apollo missions.

What they found was that areas of the Moon’s surface that had been previously mapped showed evidence of water in nearly all the large pyroclastic deposits. This included the deposits that were near the Apollo 15 and 17 landing sites where the lunar samples were obtained. From this, they determined that these samples were not anomalous in nature, and that water is distributed across the lunar surface.

What’s more, these findings could indicate that the Moon’s mantle is water-rich as well. Beyond being good news for future lunar missions, and the construction of a lunar settlement, these results could lead to a rethinking of how the Moon formed. This research was part of Shuai Li’s – a recent graduate of the University of Brown and the lead author on the study – Ph.D thesis. As he said of the study’s findings:

“The growing evidence for water inside the Moon suggest that water did somehow survive, or that it was brought in shortly after the impact by asteroids or comets before the Moon had completely solidified. The exact origin of water in the lunar interior is still a big question.

What’s more, Li indicated that lunar water that is located in volcanic deposits could be a boon for future lunar missions. “Other studies have suggested the presence of water ice in shadowed regions at the lunar poles, but the pyroclastic deposits are at locations that may be easier to access,” he said. “Anything that helps save future lunar explorers from having to bring lots of water from home is a big step forward, and our results suggest a new alternative.”

Between NASA, the ESA, Roscosmos, the ISRO and the China National Space Administration (CNSA), there are no shortage of plans to explore the Moon in the future, not to mention establishing a permanent base there. Knowing there’s abundant surface water (and maybe more in the interior as well) is therefore very good news. This water could be used to create hydrazine fuel, which would significantly reduce the costs of individual missions to the Moon.

It also makes the idea of a stopover base on the Moon, where ships traveling deeper into space could refuel and resupply – a move which would shave billions off of deep-space missions. An abundant source of local water could also ensure a ready supply of drinking and irrigation water for future lunar outposts. This would also reduce costs by ensuring that not all supplies would need to be shipped from Earth.

On top of all that, the ability to conduct experiments into how plants grow in reduced gravity would yield valuable information that could be used for long-term missions to Mars and other Solar bodies. It could therefore be said, without a trace of exaggeration, that water on the Moon is the key to future space missions.

The research was funded by the NASA Lunar Advanced Science and Exploration Research (LASER) program, which seeks to enhance lunar basic science and lunar exploration science.

Further Reading: Brown University

What is Moon Mining?

Ever since we began sending crewed missions to the Moon, people have been dreaming of the day when we might one day colonize it. Just imagine, a settlement on the lunar surface, where everyone constantly feels only about 15% as heavy as they do here on Earth. And in their spare time, the colonists get to do all kinds of cool research trek across the surface in lunar rovers. Gotta admit, it sounds fun!

More recently, the idea of prospecting and mining on the Moon has been proposed. This is due in part to renewed space exploration, but also the rise of private aerospace companies and the NewSpace industry. With missions to the Moon schedules for the coming years and decades, it seems logical to thinking about how we might set up mining and other industries there as well?

Proposed Methods:

Several proposals have been made to establish mining operations on the Moon; initially by space agencies like NASA, but more recently by private interests. Many of the earliest proposals took place during the 1950s, in response to the Space Race, which saw a lunar colony as a logical outcome of lunar exploration.

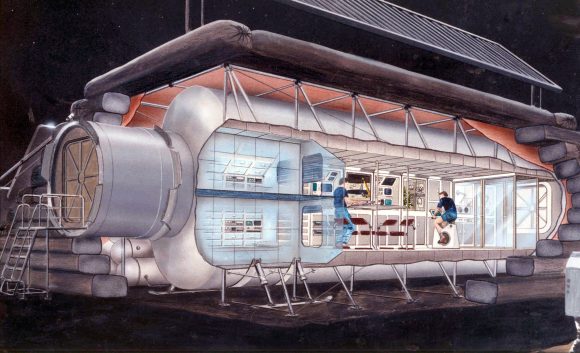

For instance, in 1954 Arthur C. Clarke proposed a lunar base where inflatable modules were covered in lunar dust for insulation and communications were provided by a inflatable radio mast. And in 1959, John S. Rinehart – the director of the Mining Research Laboratory at the Colorado School of Mines – proposed a tubular base that would “float” across the surface.

Since that time, NASA, the US Army and Air Force, and other space agencies have issued proposals for the creation of a lunar settlement. In all cases, these plans contained allowances for resource utilization to make the base as self-sufficient as possible. However, these plans predated the Apollo program, and were largely abandoned after its conclusion. It has only been in the past few decades that detailed proposals have once again been made.

For instance, during the Bush Administration (2001-2009), NASA entrtained the possibility of creating a “lunar outpost”. Consistent with their Vision for Space Exploration (2004), the plan called for the construction of a base on the Moon between 2019 and 2024. One of the key aspects of this plan was the use of ISRU techniques to produce oxygen from the surrounding regolith.

These plans were cancelled by the Obama administration and replaced with a plan for a Mars Direct mission (known as NASA’s “Journey to Mars“). However, during a workshop in 2014, representatives from NASA met with Harvard geneticist George Church, Peter Diamandis from the X Prize Foundation and other experts to discuss low-cost options for returning to the Moon.

The workshop papers, which were published in a special issue of New Space, describe how a settlement could be built on the Moon by 2022 for just $10 billion USD. According to their papers, a low-cost base would be possible thanks to the development of the space launch business, the emergence of the NewSpace industry, 3D printing, autonomous robots, and other recently-developed technologies.

In December of 2015, an international symposium titled “Moon 2020-2030 – A New Era of Coordinated Human and Robotic Exploration” took place at the the European Space Research and Technology Center. At the time, the new Director General of the ESA (Jan Woerner) articulated the agency’s desire to create an international lunar base using robotic workers, 3D printing techniques, and in-situ resources utilization.

In 2010, NASA established the Robotic Mining Competition, an annual incentive-based competition where university students design and build robots to navigate a simulated Martian environment. One of the most-important aspects of the competition is creating robots that can rely on ISRU to turn local resources into usable materials. The applications produced are also likely to be of use during future lunar missions.

Other space agencies also have plans for lunar bases in the coming decades. The Russian space agency (Roscosmos) has issued plans to build a lunar base by the 2020s, and the China National Space Agency (CNSA) proposed to build such a base in a similar timeframe, thanks to the success of its Chang’e program.

And the NewSpace industry has also been producing some interesting proposals of late. In 2010, a group of Silicon Valley entrepreneurs came together for create Moon Express, a private company that plans to offer commercial lunar robotic transportation and data services, as well as the a long-term goal of mining the Moon. In December of 2015, they became the first company competing for the Lunar X Prize to build and test a robotic lander – the MX-1.

In 2010, Arkyd Astronautics (renamed Planetary Resources in 2012) was launched for the purpose of developing and deploying technologies for asteroid mining. In 2013, Deep Space Industries was formed with the same purpose in mind. Though these companies are focused predominantly on asteroids, the appeal is much the same as lunar mining – which is expanding humanity’s resource base beyond Earth.

Resources:

Based on the study of lunar rocks, which were brought back by the Apollo missions, scientists have learned that the lunar surface is rich in minerals. Their overall composition depends on whether the rocks came from lunar maria (large, dark, basaltic plains formed from lunar eruptions) or the lunar highlands.

Rocks obtained from lunar maria showed large traces of metals, with 14.9% alumina (Al²O³), 11.8% calcium oxide (lime), 14.1% iron oxide, 9.2% magnesia (MgO), 3.9% titanium dioxide (TiO²) and 0.6% sodium oxide (Na²O). Those obtained from the lunar highlands are similar in composition, with 24.0% alumina, 15.9% lime, 5.9% iron oxide, 7.5% magnesia, and 0.6% titanium dioxide and sodium oxide.

These same studies have shown that lunar rocks contain large amounts of oxygen, predominantly in the form of oxidized minerals. Experiments have been conducted that have shown how this oxygen could be extracted to provide astronauts with breathable air, and could be used to make water and even rocket fuel.

The Moon also has concentrations of Rare Earth Metals (REM), which are attractive for two reasons. On the one hand, REMs are becoming increasingly important to the global economy, since they are used widely in electronic devices. On the other hand, 90% of current reserves of REMs are controlled by China; so having a steady access to an outside source is viewed by some as a national security matter.

Similarly, the Moon has significant amounts of water contained within its lunar regolith and in the permanently shadowed areas in its north and southern polar regions.This water would also be valuable as a source of rocket fuel, not to mention drinking water for astronauts.

In addition, lunar rocks have revealed that the Moon’s interior may contain significant sources of water as well. And from samples of lunar soil, it is calculated that adsorbed water could exist at trace concentrations of 10 to 1000 parts per million. Initially, it was though that concentrations of water within the moon rocks was the result of contamination.

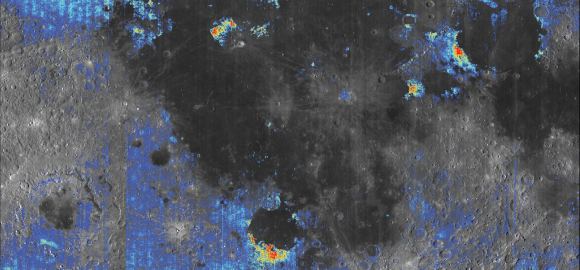

But since that time, multiple missions have not only found samples of water on the lunar surface, but revealed evidence of where it came from. The first was India’s Chandrayaan-1 mission, which sent an impactor to the lunar surface on Nov. 18th, 2008. During its 25-minute descent, the impact probe’s Chandra’s Altitudinal Composition Explorer (CHACE) found evidence of water in the Moon’s thin atmosphere.

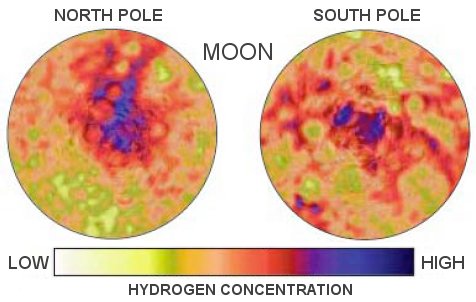

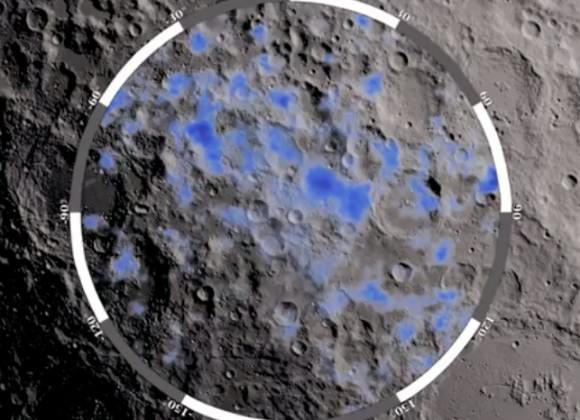

In March of 2010, the Mini-RF instrument on board Chandrayaan-1 discovered more than 40 permanently darkened craters near the Moon’s north pole that are hypothesized to contain as much as 600 million metric tonnes (661.387 million US tons) of water-ice.

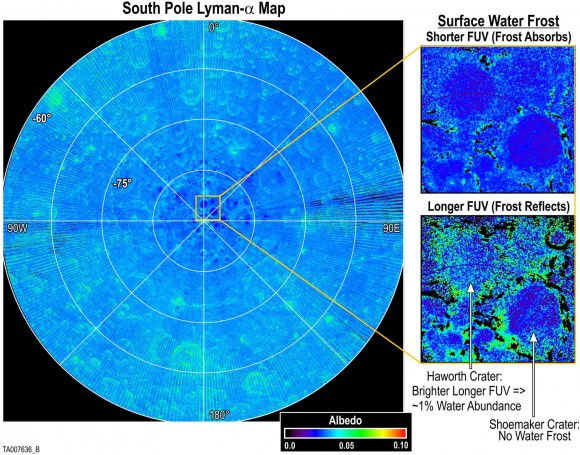

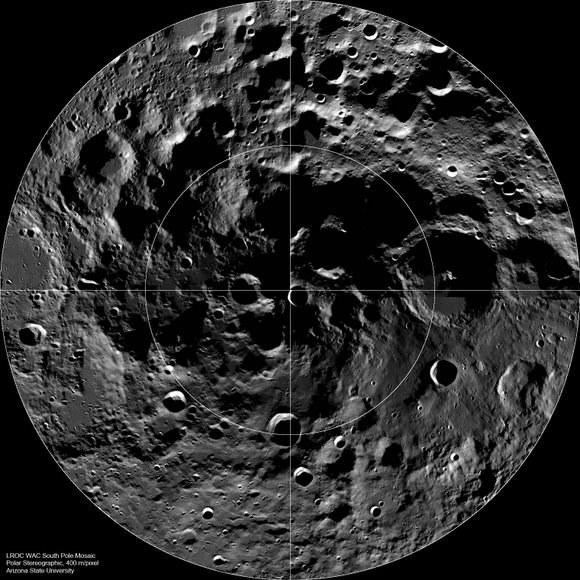

In November 2009, the NASA LCROSS space probe made similar finds around the southern polar region, as an impactor it sent to the surface kicked up material shown to contain crystalline water. In 2012, surveys conducted by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) revealed that ice makes up to 22% of the material on the floor of the Shakleton crater (located in the southern polar region).

It has been theorized that all this water was delivered by a combination of mechanisms. For one, regular bombardment by water-bearing comets, asteroids and meteoroids over geological timescales could have deposited much of it. It has also been argued that it is being produced locally by the hydrogen ions of solar wind combining with oxygen-bearing minerals.

But perhaps the most valuable commodity on the surface of the Moon might be helium-3. Helium-3 is an atom emitted by the Sun in huge amounts, and is a byproduct of the fusion reactions that take place inside. Although there is little demand for helium-3 today, physicists think they’ll serve as the ideal fuel for fusion reactors.

The Sun’s solar wind carries the helium-3 away from the Sun and out into space – eventually out of the Solar System entirely. But the helium-3 particles can crash into objects that get in their way, like the Moon. Scientists haven’t been able to find any sources of helium-3 here on Earth, but it seems to be on the Moon in huge quantities.

Benefits:

From a commercial and scientific point of view, there are several reasons why Moon mining would be beneficial to humanity. For starters, it would be absolutely essential to any plans to build a settlement on the Moon, as in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) would be far more cost effective than transporting materials from Earth.

Also, it is predicted that the proposed space exploration efforts for the 21st century will require large amounts of materiel. That which is mined on the Moon would be launched into space at a fraction of the cost of what is mined here on Earth, due to the Moon’s much lower gravity and escape velocity.

In addition, the Moon has an abundance of raw materials that humanity relies on. Much like Earth, it is composed of silicate rocks and metals that are differentiated between a geochemically distinct layers. These consist of is iron-rich inner core, and iron-rich fluid outer core, a partially molten boundary layer, and a solid mantle and crust.

In addition, it has been recognized for some time that a lunar base – which would include resource operations – would be a boon for missions farther into the Solar System. For missions heading to Mars in the coming decades, the outer Solar System, or even Venus and Mercury, the ability to be resupplied from an lunar outpost would cut the cost of individual missions drastically.

Challenges:

Naturally, the prospect of setting up mining interests on the Moon also presents some serious challenges. For instance, any base on the Moon would need to be protected from surface temperatures, which range from very low to high – 100 K (-173.15 °C;-279.67 °F) to 390 K (116.85 °C; 242.33 °F) – at the equator and average 150 K (-123.15 °C;-189.67 °F) in the polar regions.

![Schematic showing the stream of charged hydrogen ions carried from the Sun by the solar wind. One possible scenario to explain hydration of the lunar surface is that during the daytime, when the Moon is exposed to the solar wind, hydrogen ions liberate oxygen from lunar minerals to form OH and H2O, which are then weakly held to the surface. At high temperatures (red-yellow) more molecules are released than adsorbed. When the temperature decreases (green-blue) OH and H2O accumulate. [Image courtesy of University of Maryland/F. Merlin/McREL]](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/09/water-on-the-moon.jpg)

Then there’s the Moon dust, which is an extremely abrasive glassy substance that has been formed by billions of years of micrometeorite impacts on the surface. Due to the absence of weathering and erosion, Moon dust is unrounded and can play havoc with machinery, and poses a health hazard. Worst of all, its sticks to everything it touches, and was a major nuisance for the Apollo crews!

And while the lower gravity is attractive as far as launches are concerned, it is unclear what the long-term health effects of it will be on humans. As repeated research has shown, exposure to zero-gravity over month-long periods causes muscular degeneration and loss of bone density, as well as diminished organ function and a depressed immune system.

In addition, there are the potential legal hurdles that lunar mining could present. This is due to the “The Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies” – otherwise known as “The Outer Space Treaty”. In accordance with this treaty, which is overseen by the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, no nation is permitted to own land on the Moon.

And while there has been plenty of speculation about a “loophole” which does not expressly forbid private ownership, there is no legal consensus on this. As such, as lunar prospecting and mining become more of a possibility, a legal framework will have to be worked out that ensures everything is on the up and up.

Though it might be a long way off, it is not unreasonable to think that someday, we could be mining the Moon. And with its rich supplies of metals (which includes REMs) becoming part of our economy, we could be looking at a future characterized by post-scarcity!

We have written many articles on Moon mining and colonization here at Universe Today. Here’s Who Were the First Men on the Moon?, What were the First Lunar Landings?, How Many People have Walked on the Moon?, Can you Buy Land on the Moon?, and Building A Space Base, Part 1: Why Mine On The Moon Or An Asteroid?

For more information, be sure to check out this infographic on Moon Mining from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Astronomy Cast also has some interesting episodes on the subject. Listen here – Episode 17: Where Did the Moon Come From? and Episode 113: The Moon – Part I.

Sources:

Scientists Identify the Source of the Moon’s Water

Over the course of the past few decades, our ongoing exploration the Solar System has revealed some surprising discoveries. For example, while we have yet to find life beyond our planet, we have discovered that the elements necessary for life (i.e organic molecules, volatile elements, and water) are a lot more plentiful than previously thought. In the 1960’s, it was theorized that water ice could exist on the Moon; and by the next decade, sample return missions and probes were confirming this.

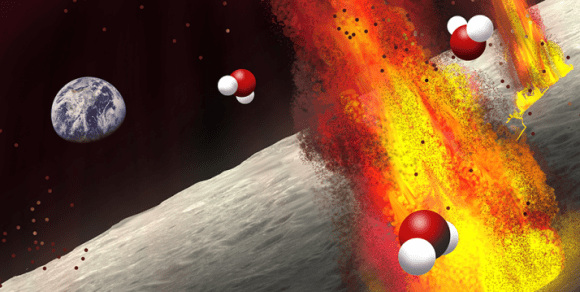

Since that time, a great deal more water has been discovered, which has led to a debate within the scientific community as to where it all came from. Was it the result of in-situ production, or was it delivered to the surface by water-bearing comets, asteroids and meteorites? According to a recent study produced by a team of scientists from the UK, US and France, the majority of the Moon’s water appears to have come from meteorites that delivered water to Earth and the Moon billions of years ago.

For the sake of their study, which appeared recently in Nature Communications, the international research team examined the samples of lunar rock and soil that were returned by the Apollo missions. When these samples were originally examined upon their return to Earth, it was assumed that the trace of amounts of water they contained were the result of contamination from Earth’s atmosphere since the containers in which the Moon rocks were brought home weren’t airtight. The Moon, it was widely believed, was bone dry.

However, a 2008 study revealed that the samples of volcanic glass beads contained water molecules (46 parts per million), as well as various volatile elements (chlorine, fluoride and sulfur) that could not have been the result of contamination. This was followed up by the deployment of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and the Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) in 2009, which discovered abundant supplies of water around the southern polar region,

However, that which was discovered on the surface paled in comparison the water that was discovered beneath it. Evidence of water in the interior was first revealed by the ISRO’s Chandrayaan-1 lunar orbiter – which carried the NASA’s Moon Mineralogy Mapper (M3) and delivered it to the surface. Analysis of this and other data has showed that water in the Moon’s interior is up to a million times more abundant than what’s on the surface.

The presence of so much water beneath the surface has begged the question, where did it all come from? Whereas water that exists on the Moon’s surface in lunar regolith appears to be the result of interaction with solar wind, this cannot account for the abundant sources deep underground. A previous study suggested that it came from Earth, as the leading theory for the Moon’s formation is that a large Mars-sized body impacted our nascent planet about 4.5 billion years ago, and the resulting debris formed the Moon. The similarity between water isotopes on both bodies seems to support that theory.

However, according to Dr. David A. Kring, a member of the research team that was led by Jessica Barnes from Open University, this explanation can only account for about a quarter of the water inside the moon. This, apparently, is due to the fact that most of the water would not have survived the processes involved in the formation of the Moon, and keep the same ratio of hydrogen isotopes.

Instead, Kring and his colleagues examined the possibility that water-bearing meteorites delivered water to both (hence the similar isotopes) after the Moon had formed. As Dr. Kring told Universe Today via email:

“The current study utilized analyses of lunar samples that had been collected by the Apollo astronauts, because those samples provide the best measure of the water inside the Moon. We compared those analyses with analyses of meteoritic samples from asteroids and spacecraft analyses of comets.”

By comparing the ratios of hydrogen to deuterium (aka. “heavy hydrogen”) from the Apollo samples and known comets, they determined that a combination of primitive meteorites (carbonaceous chondrite-type) were responsible for the majority of water to be found in the Moon’s interior today. In addition, they concluded that these types of comets played an important role when it comes to the origins of water in the inner Solar System.

For some time, scientists have argued that the abundance of water on Earth may be due in part to impacts from comets, trans-Neptunian objects or water-rich meteoroids. Here too, this was based on the fact that the ratio of the hydrogen isotopes (deuterium and protium) in asteroids like 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko revealed a similar percentage of impurities to carbon-rich chondrites that were found in the Earth’s coeans.

But how much of Earth’s water was delivered, how much was produced indigenously, and whether or not the Moon was formed with its water already there, have remained the subject of much scholarly debate. Thank to this latest study, we may now have a better idea of how and when meteorites delivered water to both bodies, thus giving us a better understanding of the origins of water in the inner Solar System.

“Some meteoritic samples of asteroids contain up to 20% water,” said Kring. “That reservoir of material – that is asteroids – are closer to the Earth-Moon system and, logically, have always been a good candidate source for the water in the Earth-Moon system. The current study shows that to be true. That water was apparently delivered 4.5 to 4.3 billion years ago.“

The existence of water on the Moon has always been a source of excitement, particularly to those who hope to see a lunar base established there someday. By knowing the source of that water, we can also come to know more about the history of the Solar System and how it came to be. It will also come in handy when it comes time to search for other sources of water, which will always be a factor when trying to establishing outposts and even colonies throughout the Solar System.

Further Reading: Nature Communications

The Moon

Look up in the night sky. On a clear night, if you’re lucky, you’ll catch a glimpse of the Moon shining in all it’s glory. As Earth‘s only satellite, the Moon has orbited our planet for over three and a half billion years. There has never been a time when human beings haven’t been able to look up at the sky and see the Moon looking back at them.

As a result, it has played a vital role in the mythological and astrological traditions of every human culture. A number of cultures saw it as a deity while others believed that its movements could help them to predict omens. But it is only in modern times that the true nature and origins of the Moon, not to mention the influence it has on planet Earth, have come to be understood.

Size, Mass and Orbit:

With a mean radius of 1737 km and a mass of 7.3477 x 10²² kg, the Moon is 0.273 times the size of Earth and 0.0123 as massive. Its size, relative to Earth, makes it quite large for a satellite – second only to Charon‘s size relative to Pluto. With a mean density of 3.3464 g/cm³, it is 0.606 times as dense as Earth, making it the second densest moon in our Solar System (after Io). Last, it has a surface gravity equivalent to 1.622 m/s2, which is 0.1654 times, or 17%, the Earth standard (g).

The Moon’s orbit has a minor eccentricity of 0.0549, and orbits our planet at a distance of between 356,400-370,400 km at perigee and 404,000-406,700 km at apogee. This gives it an average distance (semi-major axis) of 384,399 km, or 0.00257 AU. The Moon has an orbital period of 27.321582 days (27 d 7 h 43.1 min), and is tidally-locked with our planet, which means the same face is always pointed towards Earth.

Structure and Composition:

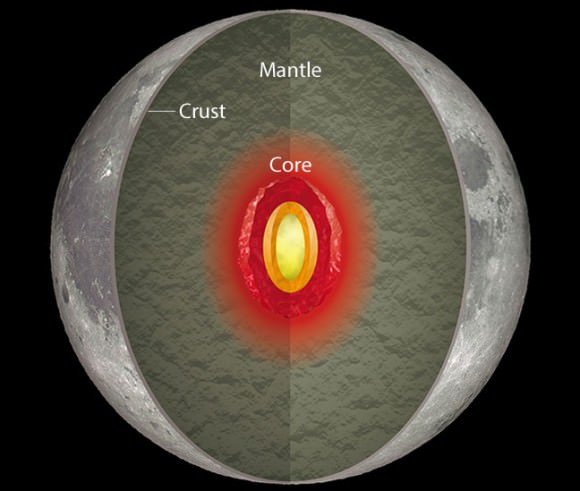

Much like Earth, the Moon has a differentiated structure that includes an inner core, an outer core, a mantle, and a crust. It’s core is a solid iron-rich sphere that measures 240 km (150 mi) across, and it surrounded by a outer core that is primarily made of liquid iron and which has a radius of roughly 300 km (190 mi).

Around the core is a partially molten boundary layer with a radius of about 500 km (310 mi). This structure is thought to have developed through the fractional crystallization of a global magma ocean shortly after the Moon’s formation 4.5 billion years ago. Crystallization of this magma ocean would have created a mantle rich in magnesium and iron nearer to the top, with minerals like olivine, clinopyroxene, and orthopyroxene sinking lower.

The mantle is also composed of igneous rock that is rich in magnesium and iron, and geochemical mapping has indicated that the mantle is more iron rich than Earth’s own mantle. The surrounding crust is estimated to be 50 km (31 mi) thick on average, and is also composed of igneous rock.

The Moon is the second densest satellite in the Solar System after Io. However, the inner core of the Moon is small, at around 20% of its total radius. Its composition is not well constrained, but it is probably a metallic iron alloy with a small amount of sulfur and nickel and analyses of the Moon’s time-variable rotation indicate that it is at least partly molten.

The presence of water has also been confirmed on the Moon, the majority of which is located at the poles in permanently-shadowed craters, and possibly also in reservoirs located beneath the lunar surface. The widely accepted theory is that most of the water was created through the Moon’s interaction of solar wind – where protons collided with oxygen in the lunar dust to create H²O – while the rest was deposited by cometary impacts.

Surface Features:

The geology of the Moon (aka. selenology) is quite different from that of Earth. Since the Moon lacks a significant atmosphere, it does not experience weather – hence there is no wind erosion. Similarly, since it lacks liquid water, there is also no erosion caused by flowing water on its surface. Because of its small size and lower gravity, the Moon cooled more rapidly after forming, and does not experience tectonic plate activity.

Instead, the complex geomorphology of the lunar surface is caused by a combination of processes, particularly impact cratering and volcanoes. Together, these forces have created a lunar landscape that is characterized by impact craters, their ejecta, volcanoes, lava flows, highlands, depressions, wrinkle ridges and grabens.

The most distinctive aspect of the Moon is the contrast between its bright and dark zones. The lighter surfaces are known as the “lunar highlands” while the darker plains are called maria (derived from the Latin mare, for “sea”). The highlands are made of igneous rock that is predominately composed of feldspar, but also contains trace amounts of magnesium, iron, pyroxene, ilmenite, magnetite, and olivine.

Mare regions, in contrast, are formed from basalt (i.e. volcanic) rock. The maria regions often coincide with the “lowlands,” but it is important to note that the lowlands (such as within the South Pole-Aitken basin) are not always covered by maria. The highlands are older than the visible maria, and hence are more heavily cratered.

Other features include rilles, which are long, narrow depressions that resemble channels. These generally fall into one of three categories: sinuous rilles, which follow meandering paths; arcuate rilles, which have a smooth curve; and linear rilles, which follow straight paths. These features are often the result of the formation of localized lava tubes that have since cooled and collapsed, and can be traced back to their source (old volcanic vents or lunar domes).

Lunar domes are another feature that is related to volcanic activity. When relatively viscous, possibly silica-rich lava erupts from local vents, it forms shield volcanoes that are referred to as lunar domes. These wide, rounded, circular features have gentle slopes, typically measure 8-12 km in diameter and rise to an elevation of a few hundred meters at their midpoint.

Wrinkle ridges are features created by compressive tectonic forces within the maria. These features represent buckling of the surface and form long ridges across parts of the maria. Grabens are tectonic features that form under extension stresses and which are structurally composed of two normal faults, with a down-dropped block between them. Most grabens are found within the lunar maria near the edges of large impact basins.

Impact craters are the Moon’s most common feature, and are created when a solid body (an asteroid or comet) collides with the surface at a high velocity. The kinetic energy of the impact creates a compression shock wave that creates a depression, followed by a rarefaction wave that propels most of the ejecta out of the crater, and then a rebounds to form a central peak.

These craters range in size from tiny pits to the immense South Pole–Aitken Basin, which has a diameter of nearly 2,500 km and a depth of 13 km. In general, the lunar history of impact cratering follows a trend of decreasing crater size with time. In particular, the largest impact basins were formed during the early periods, and these were successively overlaid by smaller craters.

There are estimated to be roughly 300,000 craters wider than 1 km (0.6 mi) on the Moon’s near side alone. Some of these are named for scholars, scientists, artists and explorers. The lack of an atmosphere, weather and recent geological processes mean that many of these craters are well-preserved.

Another feature of the lunar surface is the presence of regolith (aka. Moon dust, lunar soil). Created by billions of years of collisions by asteroids and comets, this fine grain of crystallized dust covers much of the lunar surface. The regolith contains rocks, fragments of minerals from the original bedrock, and glassy particles formed during the impacts.

The chemical composition of the regolith varies according to its location. Whereas the regolith in the highlands is rich in aluminum and silica, the regolith in the maria is rich in iron and magnesium and is silica-poor, as are the basaltic rocks from which it is formed.

Geological studies of the Moon are based on a combination of Earth-based telescope observations, measurements from orbiting spacecraft, lunar samples, and geophysical data. A few locations were sampled directly during the Apollo missions in the late 1960s and early 1970s, which returned approximately 380 kilograms (838 lb) of lunar rock and soil to Earth, as well as several missions of the Soviet Luna programme.

Atmosphere:

Much like Mercury, the Moon has a tenuous atmosphere (known as an exosphere), which results in severe temperature variations. These range from -153°C to 107°C on average, though temperatures as low as -249°C have been recorded. Measurements from NASA’s LADEE have mission determined the exosphere is mostly made up of helium, neon and argon.

The helium and neon are the result of solar wind while the argon comes from the natural, radioactive decay of potassium in the Moon’s interior. There is also evidence of frozen water existing in permanently shadowed craters, and potentially below the soil itself. The water may have been blown in by the solar wind or deposited by comets.

Formation:

Several theories have been proposed for the formation of the Moon. These include the fission of the Moon from the Earth’s crust through centrifugal force, the Moon being a preformed object that was captured by Earth’s gravity, and the Earth and Moon co-forming together in the primordial accretion disk. The estimated age of the Moon also ranges from it being formed 4.40-4.45 billion years ago to 4.527 ± 0.010 billion years ago, roughly 30–50 million years after the formation of the Solar System.

The prevailing hypothesis today is that the Earth-Moon system formed as a result of an impact between the newly-formed proto-Earth and a Mars-sized object (named Theia) roughly 4.5 billion years ago. This impact would have blasted material from both objects into orbit, where it eventually accreted to form the Moon.

This has become the most accepted hypothesis for several reasons. For one, such impacts were common in the early Solar System, and computer simulations modelling the impact are consistent with the measurements of the Earth-Moon system’s angular momentum, as well as the small size of the lunar core.

In addition, examinations of various meteorites show that other inner Solar System bodies (such as Mars and Vesta) have very different oxygen and tungsten isotopic compositions to Earth. In contrast, examinations of the lunar rocks brought back by the Apollo missions show that Earth and the Moon have nearly identical isotopic compositions.

This is the most compelling evidence suggesting that the Earth and the Moon have a common origin.

Relationship to Earth:

The Moon makes a complete orbit around Earth with respect to the fixed stars about once every 27.3 days (its sidereal period). However, because Earth is moving in its orbit around the Sun at the same time, it takes slightly longer for the Moon to show the same phase to Earth, which is about 29.5 days (its synodic period). The presence of the Moon in orbit influences conditions here on Earth in a number of ways.

The most immediate and obvious are the ways its gravity pulls on Earth – aka. it’s tidal effects. The result of this is an elevated sea level, which are commonly referred to as ocean tides. Because Earth spins about 27 times faster than the Moon moves around it, the bulges are dragged along with Earth’s surface faster than the Moon moves, rotating around Earth once a day as it spins on its axis.

The ocean tides are magnified by other effects, such as frictional coupling of water to Earth’s rotation through the ocean floors, the inertia of water’s movement, ocean basins that get shallower near land, and oscillations between different ocean basins. The gravitational attraction of the Sun on Earth’s oceans is almost half that of the Moon, and their gravitational interplay is responsible for spring and neap tides.

Gravitational coupling between the Moon and the bulge nearest the Moon acts as a torque on Earth’s rotation, draining angular momentum and rotational kinetic energy from Earth’s spin. In turn, angular momentum is added to the Moon’s orbit, accelerating it, which lifts the Moon into a higher orbit with a longer period.

As a result of this, the distance between Earth and Moon is increasing, and Earth’s spin is slowing down. Measurements from lunar ranging experiments with laser reflectors (which were left behind during the Apollo missions) have found that the Moon’s distance to Earth increases by 38 mm (1.5 in) per year.

This speeding and slowing of Earth and the Moon’s rotation will eventually result in a mutual tidal locking between the Earth and Moon, similar to what Pluto and Charon experience. However, such a scenario is likely to take billions of years, and the Sun is expected to have become a red giant and engulf Earth long before that.

The lunar surface also experiences tides of around 10 cm (4 in) amplitude over 27 days, with two components: a fixed one due to Earth (because they are in synchronous rotation) and a varying component from the Sun. The cumulative stress caused by these tidal forces produces moonquakes. Despite being less common and weaker than earthquakes, moonquakes can last longer (one hour) since there is no water to damp out the vibrations.

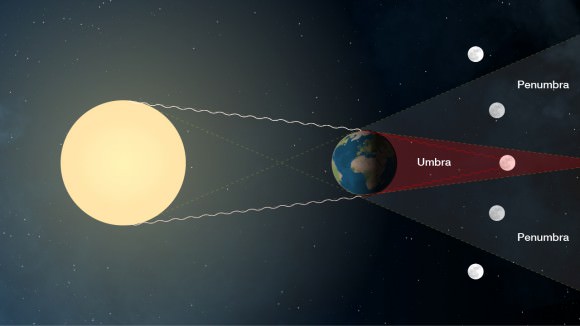

Another way the Moon effects life on Earth is through occultation (i.e. eclipses). These only happen when the Sun, the Moon, and Earth are in a straight line, and take one of two forms – a lunar eclipse and a solar eclipse. A lunar eclipse occurs when a full Moon passes behind Earth’s shadow (umbra) relative to the Sun, which causes it to darken and take on a reddish appearance (aka. a “Blood Moon” or “Sanguine Moon”.)

A solar eclipse occurs during a new Moon, when the Moon is between the Sun and Earth. Since they are the same apparent size in the sky, the moon can either partially block the Sun (annular eclipse) or fully block it (total eclipse). In the case of a total eclipse, the Moon completely covers the disc of the Sun and the solar corona becomes visible to the naked eye.

Because the Moon’s orbit around Earth is inclined by about 5° to the orbit of Earth around the Sun, eclipses do not occur at every full and new moon. For an eclipse to occur, the Moon must be near the intersection of the two orbital planes.The periodicity and recurrence of eclipses of the Sun by the Moon, and of the Moon by Earth, is described by the “Saros Cycle“, which is a period of approximately 18 years.

History of Observation:

Human beings have been observing the Moon since prehistoric times, and understanding the Moon’s cycles was one of the earliest developments in astronomy. The earliest examples of this comes from the 5th century BCE, when Babylonian astronomers had recorded the 18-year Satros cycle of lunar eclipses, and Indian astronomers had described the Moon’s monthly elongation.

The ancient Greek philosopher Anaxagoras (ca. 510 – 428 BCE) reasoned that the Sun and Moon were both giant spherical rocks, and the latter reflected the light of the former. In Aristotle’s “On the Heavens“, which he wrote in 350 BCE, the Moon was said to mark the boundary between the spheres of the mutable elements (earth, water, air and fire), and the heavenly stars – an influential philosophy that would dominate for centuries.

In the 2nd century BCE, Seleucus of Seleucia correctly theorized that tides were due to the attraction of the Moon, and that their height depends on the Moon’s position relative to the Sun. In the same century, Aristarchus computed the size and distance of the Moon from Earth, obtaining a value of about twenty times the radius of Earth for the distance. These figures were greatly improved by Ptolemy (90–168 BCE), who’s values of a mean distance of 59 times Earth’s radius and a diameter of 0.292 Earth diameters were close to the correct values (60 and 0.273 respectively).

By the 4th century BCE, the Chinese astronomer Shi Shen gave instructions for predicting solar and lunar eclipses. By the time of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), astronomers recognized that moonlight was reflected from the Sun, and Jin Fang (78–37 BC) postulated that the Moon was spherical in shape.

In 499 CE, the Indian astronomer Aryabhata mentioned in his Aryabhatiya that reflected sunlight is the cause of the shining of the Moon. The astronomer and physicist Alhazen (965–1039) found that sunlight was not reflected from the Moon like a mirror, but that light was emitted from every part of the Moon in all directions.

Shen Kuo (1031–1095) of the Song dynasty created an allegory to explain the waxing and waning phases of the Moon. According to Shen, it was comparable to a round ball of reflective silver that, when doused with white powder and viewed from the side, would appear to be a crescent.

During the Middle Ages, before the invention of the telescope, the Moon was increasingly recognized as a sphere, though many believed that it was “perfectly smooth”. In keeping with medieval astronomy, which combined Aristotle’s theories of the universe with Christian dogma, this view would later be challenged as part of the Scientific Revolution (during the 16th and 17th century) where the Moon and other planets would come to be seen as being similar to Earth.

Using a telescope of his own design, Galileo Galilei drew one of the first telescopic drawings of the Moon in 1609, which he included in his book Sidereus Nuncius (“Starry Messenger). From his observations, he noted that the Moon was not smooth, but had mountains and craters. These observations, coupled with observations of moons orbiting Jupiter, helped him to advance the heliocentric model of the universe.

Telescopic mapping of the Moon followed, which led to the lunar features being mapped in detail and named. The names assigned by Italian astronomers Giovannia Battista Riccioli and Francesco Maria Grimaldi are still in use today. The lunar map and book on lunar features created by German astronomers Wilhelm Beer and Johann Heinrich Mädler between 1834 and 1837 were the first accurate trigonometric study of lunar features, and included the heights of more than a thousand mountains.

Lunar craters, first noted by Galileo, were thought to be volcanic until the 1870s, when English astronomer Richard Proctor proposed that they were formed by collisions. This view gained support throughout the remainder of the 19th century; and by the early 20th century, led to the development of lunar stratigraphy – part of the growing field of astrogeology.

Exploration:

With the beginning of the Space Age in the mid-20th century, the ability to physically explore the Moon became possible for the first time. And with the onset of the Cold War, both the Soviet and American space programs became locked in an ongoing effort to reach the Moon first. This initially consisted of sending probes on flybys and landers to the surface, and culminated with astronauts making manned missions.

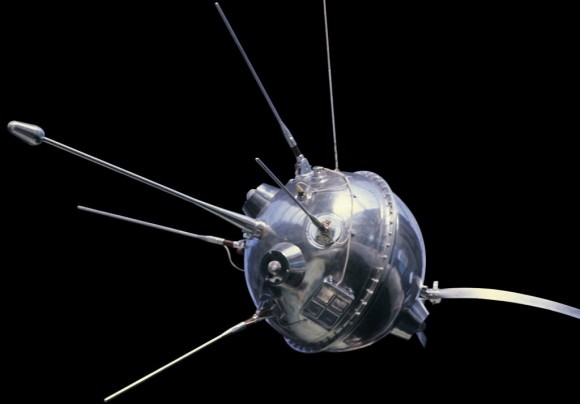

Exploration of the Moon began in earnest with the Soviet Luna program. Beginning in earnest in 1958, the programmed suffered the loss of three unmanned probes. But by 1959, the Soviets managed to successfully dispatch fifteen robotic spacecraft to the Moon and accomplished many firsts in space exploration. This included the first human-made objects to escape Earth’s gravity (Luna 1), the first human-made object to impact the lunar surface (Luna 2), and the first photographs of the far side of the Moon (Luna 3).

Between 1959 and 1979, the program also managed to make the first successful soft landing on the Moon (Luna 9), and the first unmanned vehicle to orbit the Moon (Luna 10) – both in 1966. Rock and soil samples were brought back to Earth by three Luna sample return missions – Luna 16 (1970), Luna 20 (1972), and Luna 24 (1976).

Two pioneering robotic rovers landed on the Moon – Luna 17 (1970) and Luna 21 (1973) – as a part of Soviet Lunokhod program. Running from 1969 to 1977, this program was primarily designed to provide support for the planned Soviet manned moon missions. But with the cancellation of the Soviet manned moon program, they were instead used as remote-controlled robots to photograph and explore the lunar surface.

NASA began launching probes to provide information and support for an eventual Moon landing in the early 60s. This took the form of the Ranger program, which ran from 1961 – 1965 and produced the first close-up pictures of the lunar landscape. It was followed by the Lunar Orbiter program which produced maps of the entire Moon between 1966-67, and the Surveyor program which sent robotic landers to the surface between 1966-68.

In 1969, astronaut Neil Armstrong made history by becoming the first person to walk on the Moon. As the commander of the American mission Apollo 11, he first sett foot on the Moon at 02:56 UTC on 21 July 1969. This represented the culmination of the Apollo program (1969-1972), which sought to send astronauts to the lunar surface to conduct research and be the first human beings to set foot on a celestial body other than Earth.

The Apollo 11 to 17 missions (save for Apollo 13, which aborted its planned lunar landing) sent a total of 13 astronauts to the lunar surface and returned 380.05 kilograms (837.87 lb) of lunar rock and soil. Scientific instrument packages were also installed on the lunar surface during all the Apollo landings. Long-lived instrument stations, including heat flow probes, seismometers, and magnetometers, were installed at the Apollo 12, 14, 15, 16, and 17 landing sites, some of which are still operational.

After the Moon Race was over, there was a lull in lunar missions. However, by the 1990s, many more countries became involve in space exploration. In 1990, Japan became the third country to place a spacecraft into lunar orbit with its Hiten spacecraft, an orbiter which released the smaller Hagoroma probe.

In 1994, the U.S. sent the joint Defense Department/NASA spacecraft Clementine to lunar orbit to obtain the first near-global topographic map of the Moon and the first global multispectral images of the lunar surface. This was followed in 1998 by the Lunar Prospector mission, whose instruments indicated the presence of excess hydrogen at the lunar poles, which is likely to have been caused by the presence of water ice in the upper few meters of the regolith within permanently shadowed craters.

Since the year 2000, exploration of the moon has intensified, with a growing number of parties becoming involved. The ESA’s SMART-1 spacecraft, the second ion-propelled spacecraft ever created, made the first detailed survey of chemical elements on the lunar surface while in orbit from November 15th, 2004, until its lunar impact on September 3rd, 2006.

China has pursued an ambitious program of lunar exploration under their Chang’e program. This began with Chang’e 1, which successfully obtained a full image map of the Moon during its sixteen month orbit (November 5th, 2007 – March 1st, 2009) of the Moon. This was followed in October of 2010 with the Chang’e 2 spacecraft, which mapped the Moon at a higher resolution before performing a flyby of asteroid 4179 Toutatis in December of 2012, then heading off into deep space.

On 14 December 2013, Chang’e 3 improved upon its orbital mission predecessors by landing a lunar lander onto the Moon’s surface, which in turn deployed a lunar rover named Yutu (literally “Jade Rabbit”). In so doing, Chang’e 3 made the first soft lunar landing since Luna 24 in 1976, and the first lunar rover mission since Lunokhod 2 in 1973.

Between October 4th, 2007, and June 10th, 2009, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency‘s (JAXA) Kaguya (“Selene”) mission – a lunar orbiter fitted with a high-definition video camera and two small radio-transmitter satellites – obtained lunar geophysics data and took the first high-definition movies from beyond Earth orbit.

The Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) first lunar mission, Chandrayaan I, orbited the Moon between November 2008 and August 2009 and created a high resolution chemical, mineralogical and photo-geological map of the lunar surface, as well as confirming the presence of water molecules in lunar soil. A second mission was planned for 2013 in collaboration with Roscosmos, but was cancelled.

NASA has also been busy in the new millennium. In 2009, they co-launched the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and the Lunar CRater Observation and Sensing Satellite (LCROSS) impactor. LCROSS completed its mission by making a widely observed impact in the crater Cabeus on October 9th, 2009, while the LRO is currently obtaining precise lunar altimetry and high-resolution imagery.

Two NASA Gravity Recovery And Interior Library (GRAIL) spacecraft began orbiting the Moon in January 2012 as part of a mission to learn more about the Moon’s internal structure.

Upcoming lunar missions include Russia’s Luna-Glob – an unmanned lander with a set of seismometers, and an orbiter based on its failed Martian Fobos-Grunt mission. Privately funded lunar exploration has also been promoted by the Google Lunar X Prize, which was announced on September 13th, 2007, and offers US$20 million to anyone who can land a robotic rover on the Moon and meet other specified criteria.

Under the terms of the Outer Space Treaty, the Moon remains free to all nations to explore for peaceful purposes. As our efforts to explore space continue, plans to create a lunar base and possibly even a permanent settlement may become a reality. Looking to the distant future, it wouldn’t be far fetched at all to imagine native-born humans living on the Moon, perhaps known as Lunarians (though I imagine Lunies will be more popular!)

We have many interesting articles about the Moon here at Universe Today. Below is a list that covers just about everything we know about it today. We hope you find what you are looking for:

- A Red Moon – Not a Sign of the Apocalypse!

- Africa’s First Mission to the Moon Announced

- Age of the Moon

- Building a Moon Base: Part I – Challenges and Hazards

- Building a Moon Base: Part II – Habitat Concepts

- Building a Moon Base: Part III – Structural Designs

- Building a Moon Base: Part IV – Infrastructure and Transportation

- Could We Terraform the Moon?

- Diameter of the Moon

- Did We Need the Moon for Life?

- Does the Moon Rotate?

- Earth’s Second Moon Is About To Leave Us

- Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin – the Second Man on the Moon

- Golden Spike To Offer Commercial Human Missions To The Moon

- Gravity On The Moon

- How Can You See the Moon and the Sun at the Same Time?

- How Could We Destroy the Moon?

- How Do We Know the Moon Landing Isn’t Faked?

- How Did the Moon Form?

- How Long Does it Take to Get to the Moon?

- How Many People Have Walked on the Moon?

- How NASA Filmed Humans Leaving the Moon 42 Years Ago

- Is It Time to Return to the Moon?

- Is The Moon a Planet?

- Let’s Send Neil Back To The Moon

- Make a Deal For Land on the Moon

- Neil Armstrong; 1st Human on the Moon – Apollo 11, Tributes and Photo Gallery

- Neutral Hydrogen Bouncing off the Moon

- Old NASA Equipment Will Be Visible On The Moon

- Should We Go Back to Mars or the Moon?

- The Moon is Just 95 Million Years Younger Than The Solar System

- The Moon is Toxic?

- The Sun and the Moon

- There’s Poop On The Moon

- There Could be Lava Tubes on the Moon Large Enough For Whole Cities

- This is the Moon, the Whole Moon, and Nothing but the Moon

- Making the Moon: The Practice Crater Fields of Flagstaff, Arizona

- Neil Armstrong: The First Man To Walk On The Moon

- New Crater On The Moon

- Water On The Moon Was Blown In By Solar Wind

- What are the Phases of the Moon?

- What Is A Moon?

- What Color is the Moon?

- What Is The Gibbous Moon?

- What Is The Moon Made Of?

- What Is The Moon’s Real Name?

- What is the Distance to the Moon?

- What’s On The Far Side Of The Moon?

- Where We You When Apollo 11 Landed on the Moon?

- Who Were the First Men on the Moon?

- Why Does the “Man In the Moon” Face Earth?

- Why Does the Moon Look So Big Tonight?

- Why Does the Moon Shine?

- Why Doesn’t the Sun Steal the Moon?

- Why Is The Moon Leaving Us?

- Why There are no Lunar “Seas” on the Far Side of the Moon

- Yes, There’s Water on the Moon

- You Could Fit All the Planets Between the Earth and the Moon?