It’s hard to comprehend the vast emptiness of space. Especially when we detect odd signatures, such as luminous explosions that are neither as bright nor as long as traditional supernovae, originating in the unfathomable emptiness.

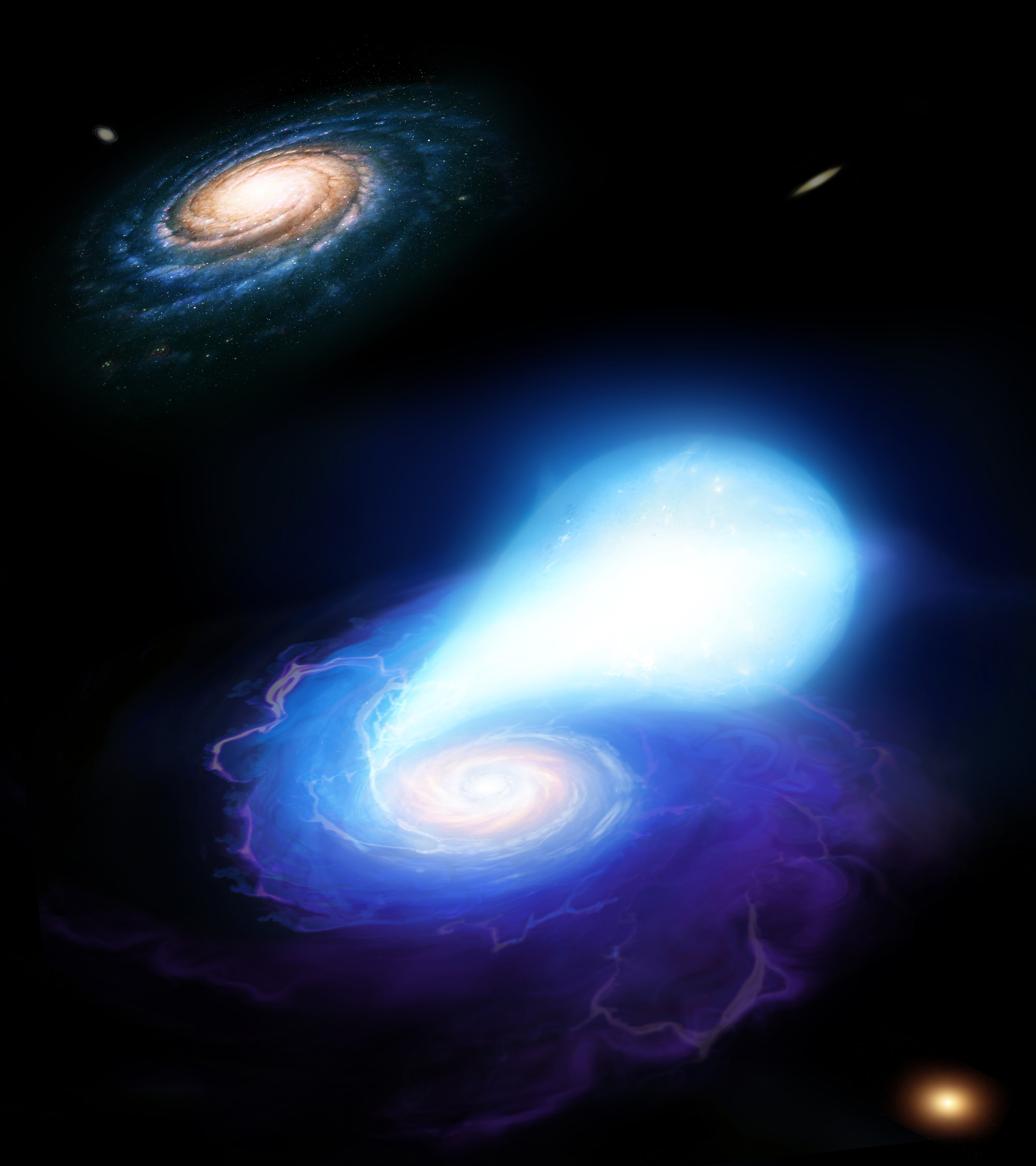

But a team of astronomers is now beginning to understand these so-called calcium-rich transients, often referred to as the Universe’s loneliest supernovae, hypothesizing that they’re created by collisions between white dwarf stars and neutron stars — both of which have been thrown out of their galaxy.

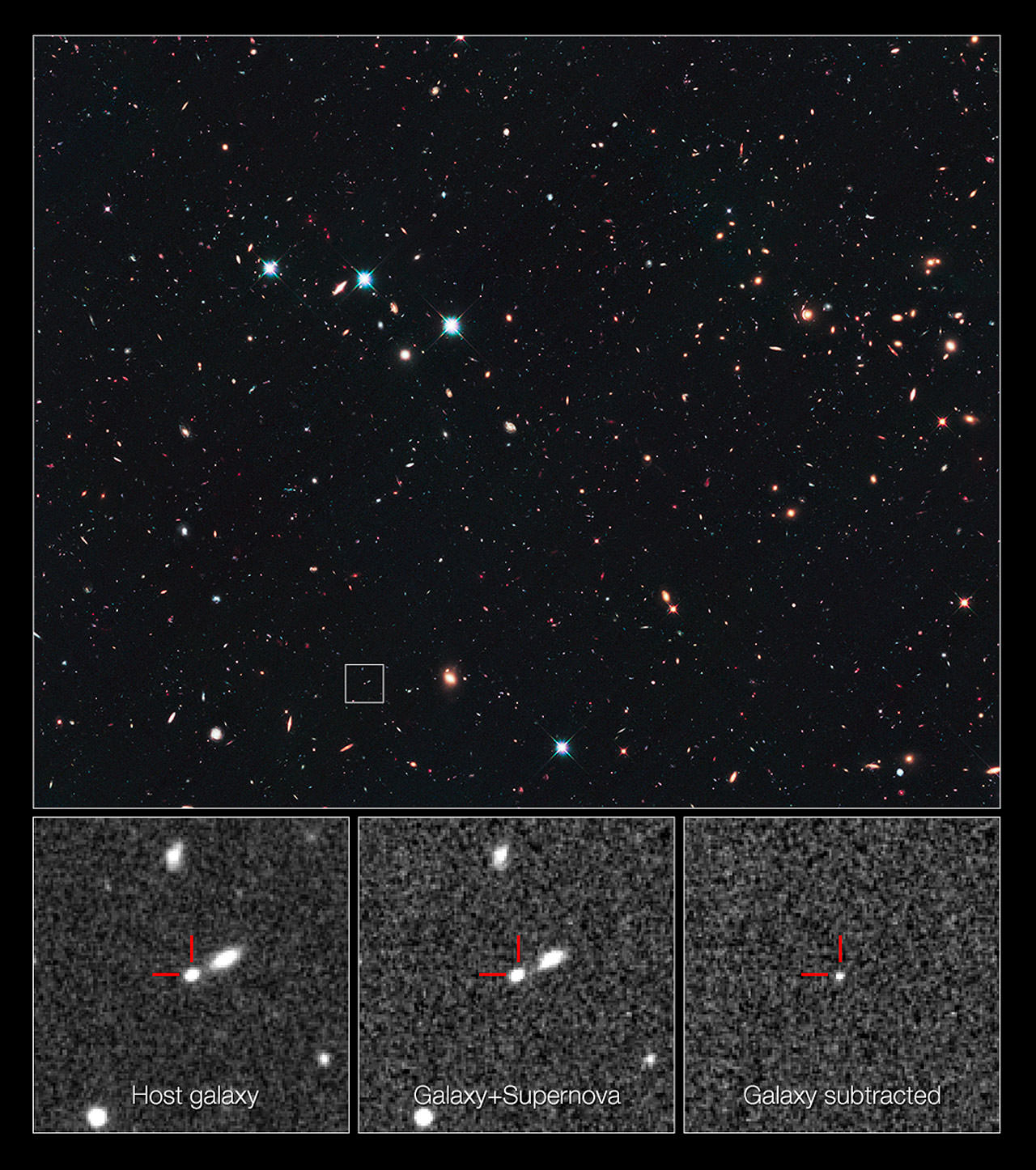

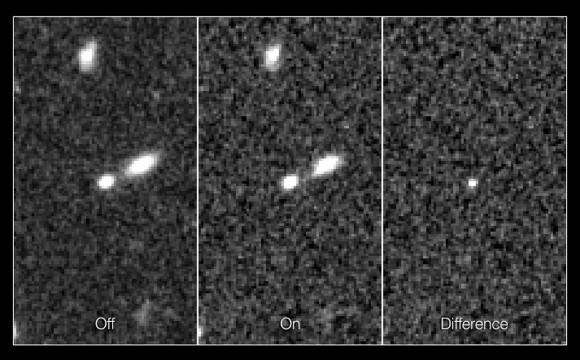

“One of the weirdest aspects is that they seem to explode in unusual places. For example, if you look at a galaxy, you expect any explosions to roughly be in line with the underlying light you see from that galaxy, since that is where the stars are” said lead author Joseph Lyman from the University of Warwick in a press release. “However, a large fraction of these are exploding at huge distances from their galaxies, where the number of stellar systems is miniscule.”

The team guessed there could be very faint dwarf galaxies, hiding beneath the limit of detection, but found nothing with our best telescopes, namely the Very Large Telescope in Chile and the Hubble Space Telescope.

“So the question becomes, how did the get there?” pondered Lyman. Roughly a third of these events occur at least 65 thousand light-years away from a potential host galaxy.

We’ve discovered dozens of so-called hypervelocity stars — single stars that escape their home galaxy, traveling rapidly throughout intergalactic space — and even one runaway globular cluster. Nature clearly has a way of kicking systems out of an entire galaxy, likely by an interaction with the supermassive black hole lurking in the center of that galaxy.

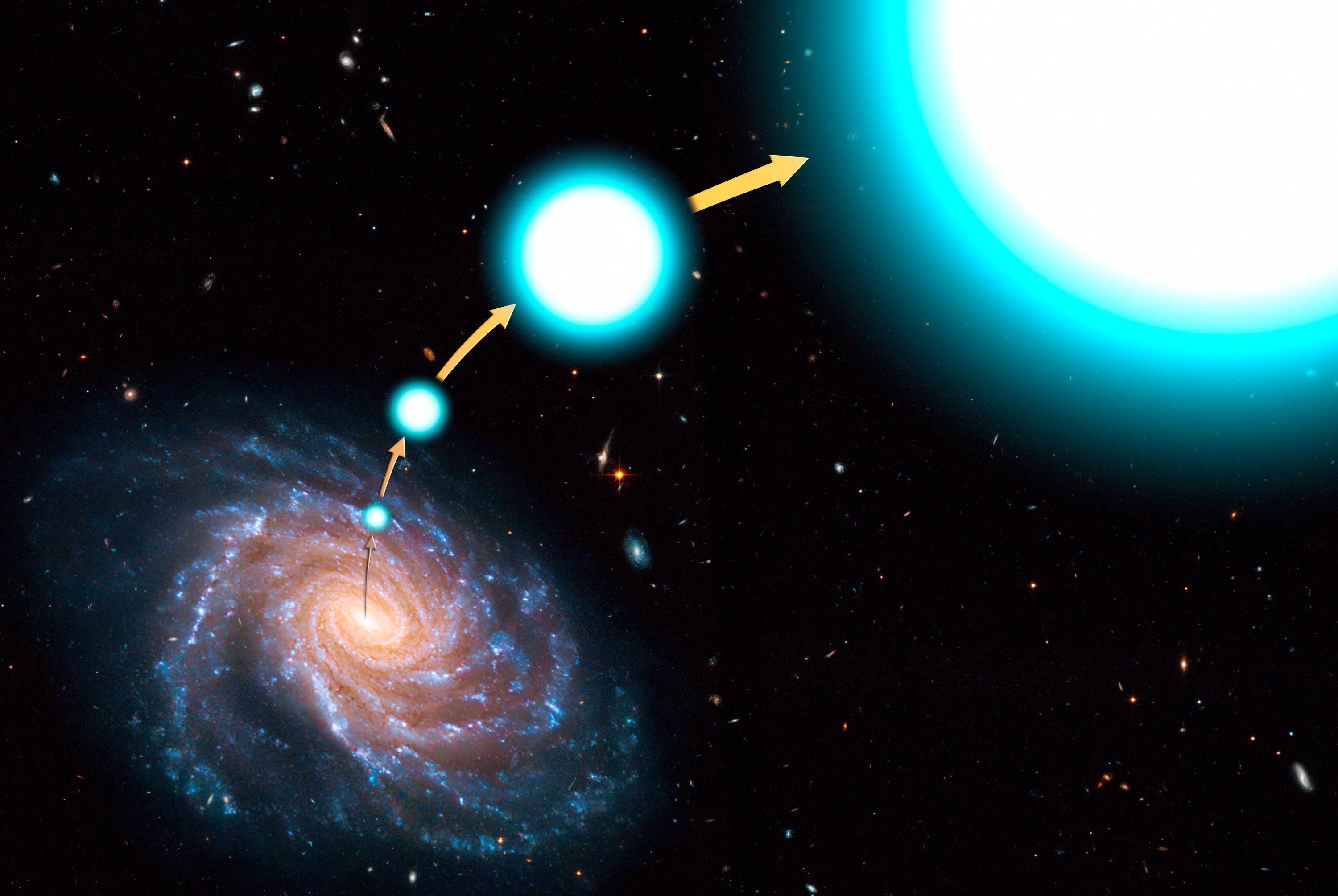

So it’s viable that the source of these supernovae was first kicked out of its host galaxy. But the second puzzle wondered what type of system could have caused such an odd explosion.

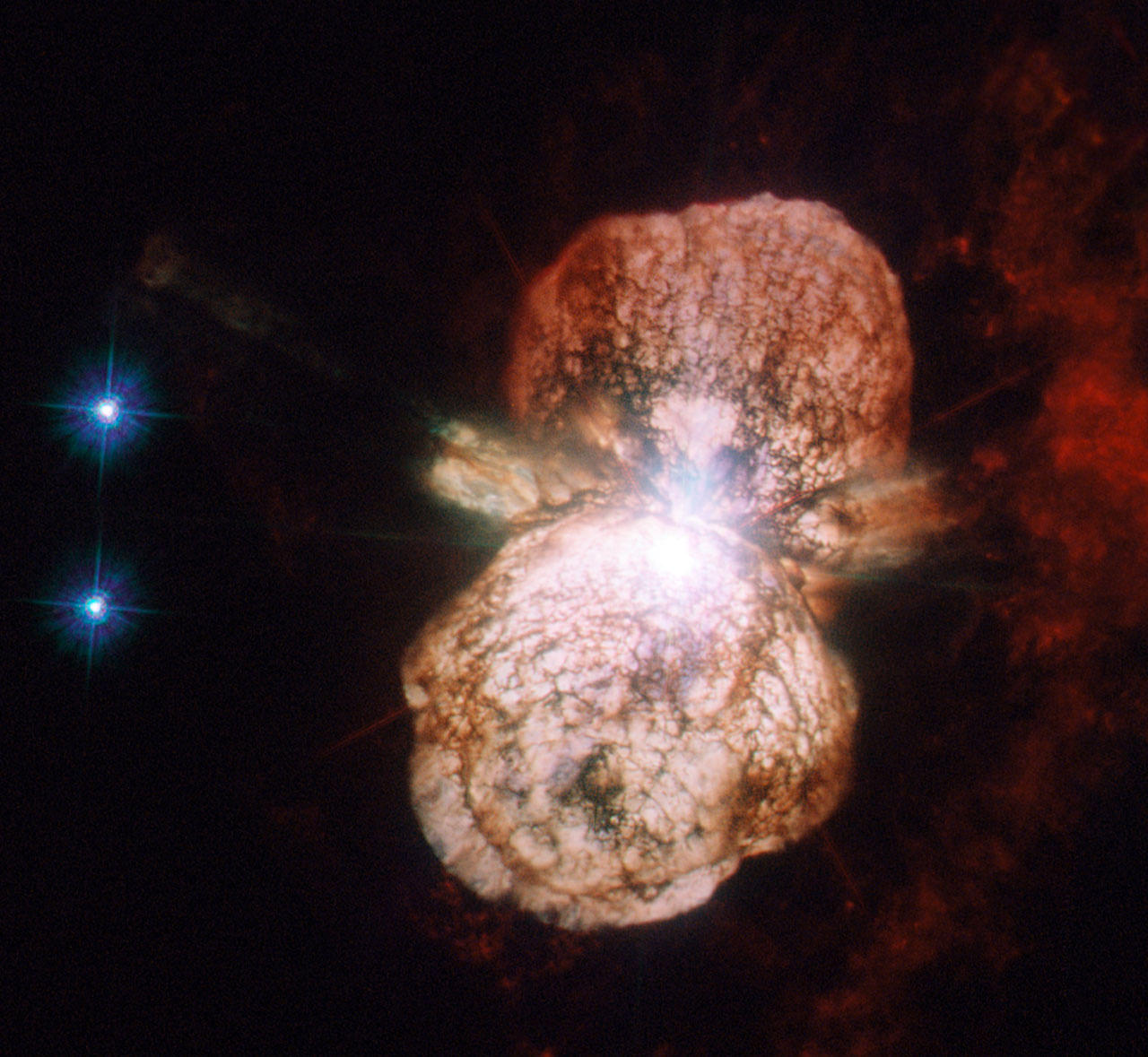

Previous studies show that calcium comprises up to half of the material thrown off in these transients, compared to only a tiny fraction in normal supernovae. It remained unclear how to explain such a calcium-rich system.

So the research team compared their data to short-duration gamma ray bursts, which are also seen to explode in remote locations with no coincident galaxy detected. We think these enigmatic bursts occur when two neutron stars collide, or when a neutron star merges with a black hole.

Alas, the research team discovered that if a neutron star collided with a white dwarf, the explosion would not only provide enough energy to generate the low luminosity of the calcium rich transients, but it would also produce calcium rich material.

“What we therefore propose is these are systems that have been ejected from their galaxy,” said Lyman. “A good candidate in this scenario is a white dwarf and a neutron star in a binary system. The neutron star is formed when a massive star goes supernova. The mechanism of the supernova explosion causes the neutron star to be ‘kicked’ to very high velocities (100s of km/s). This high velocity system can then escape its galaxy, and if the binary system survives the kick, the white dwarf and neutron star will merge causing the explosive transient.”

Any merger should also produce high-energy gamma-ray bursts, motivating further observations of any new examples.

The paper has been published today in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society and is available online.