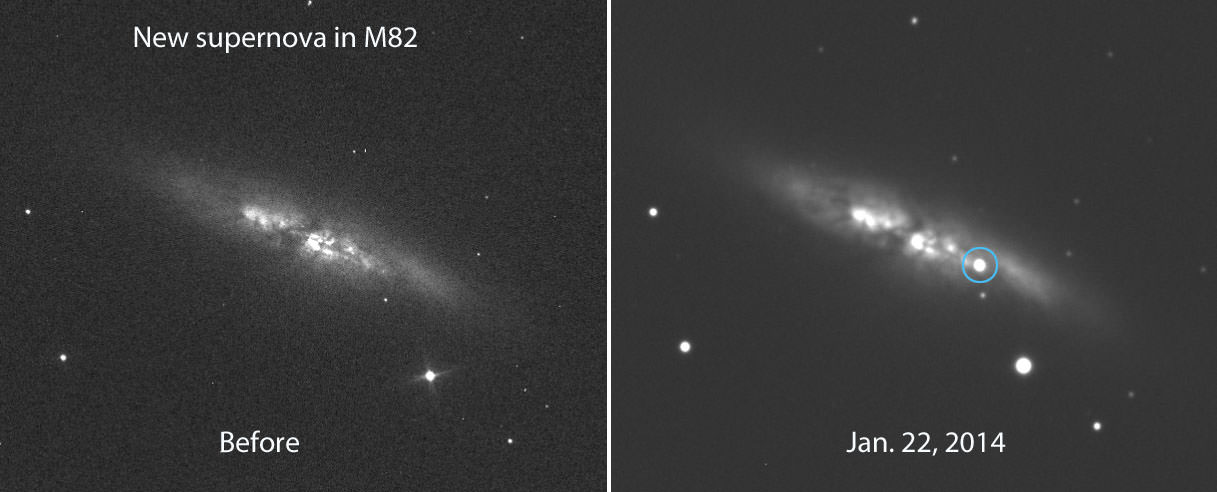

Wow! Now here’s a supernova bright enough for even small telescope observers to see. And it’s in a bright galaxy in Ursa Major well placed for viewing during evening hours in the northern hemisphere. Doesn’t get much better than that! The new object was discovered last night by S.J. Fossey; news of the outburst first appeared on the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams “Transient Objects Confirmation Page”

Astronomers are saying this new supernova is currently at magnitude +11 to +12, so its definitely not visible with the naked eye. You’ll need a 4 inch telescope at least to be able to see it. That said, at 12 million light years away, this is (at the moment) the brightest, closest supernova since SN 1993 J kaboomed in neighboring galaxy M81 21 years ago in 1993. M81 and M82, along with NGC 3077, form a close-knit interacting group.

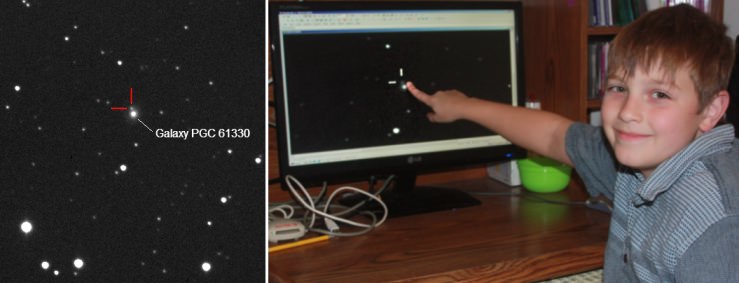

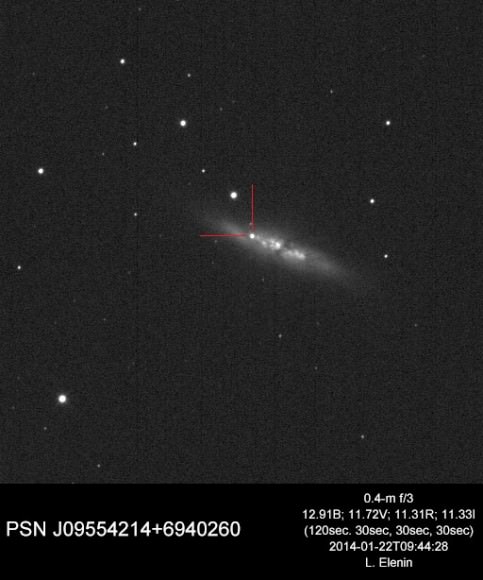

It’s amazing it wasn’t found and reported sooner (update — see below, as perhaps it was!). M82 is a popular target for beginning and amateur astronomers; pre-discovery observations show it had already brightened to magnitude 13.9 on the 16th, 13.3 on the 17th and 12.2 on the 19th. Cold winter weather and clouds to blame?

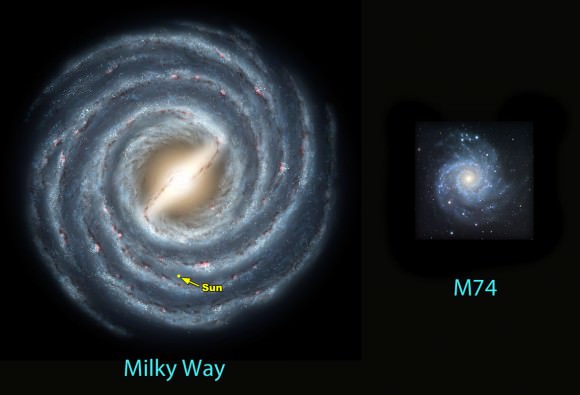

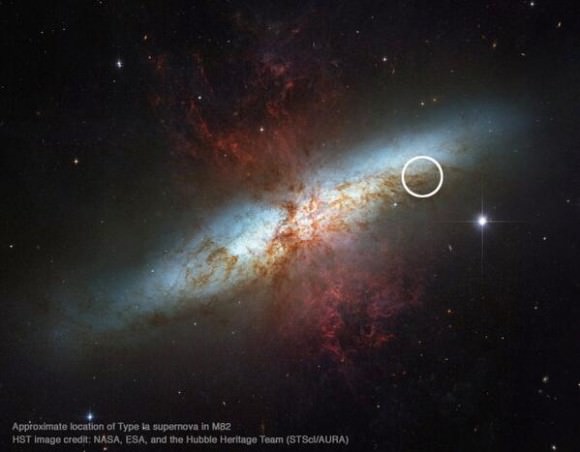

M82 is a bright, striking edge-on spiral galaxy bright enough to see in binoculars. Known as the Cigar or Starburst Galaxy because of its shape and a large, active starburst region in its core, it’s only 12 million light years from Earth and home to two previous supernovae in 2004 and 2008. Neither of those came anywhere close to the being as bright as the discovery, and it’s very possible the new object will become brighter yet.

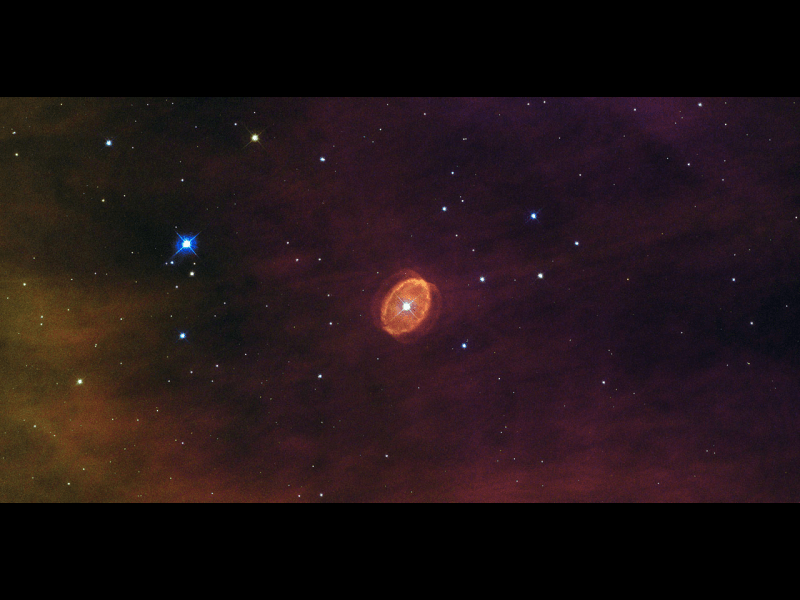

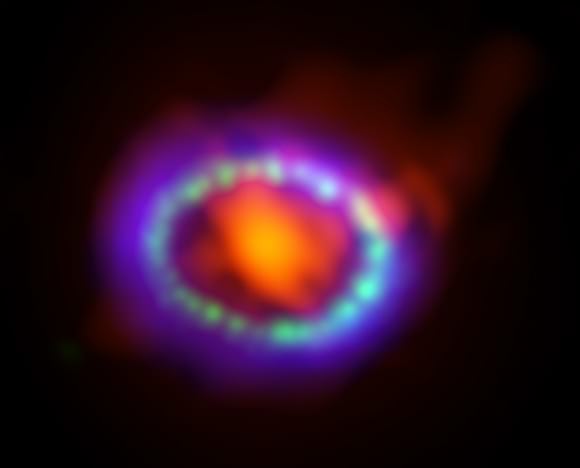

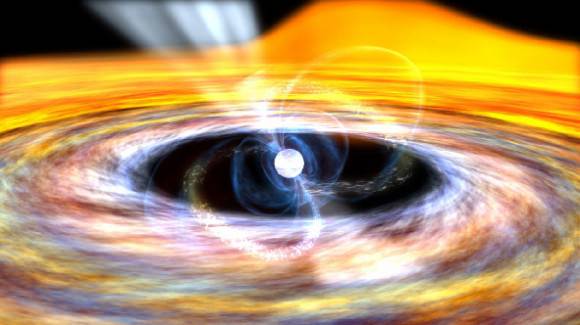

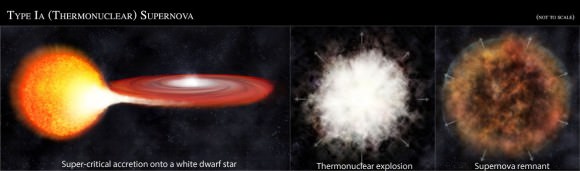

PSN J09554214+6940260 is a Type Ia supernova. Type Ia (one-a), a dry term describing one of the most catastrophic events in the universe. Here a superdense white dwarf, a star only about the size of Earth but with the gravitational power of a sun-size star, pulls hydrogen gas from a nearby companion down to its surface where it adds to the star’s weight.

When the dwarf packs enough pounds to reach a mass 1.4 times that of the sun, it can no longer support itself. The star suddenly collapses, heats to incredible temperatures and burns up explosively in a runaway fusion reaction. What we see here on Earth is the sudden appearance of a brand new star within the galaxy’s disk. Of course, it’s not really a new star, but rather the end of an aged one.

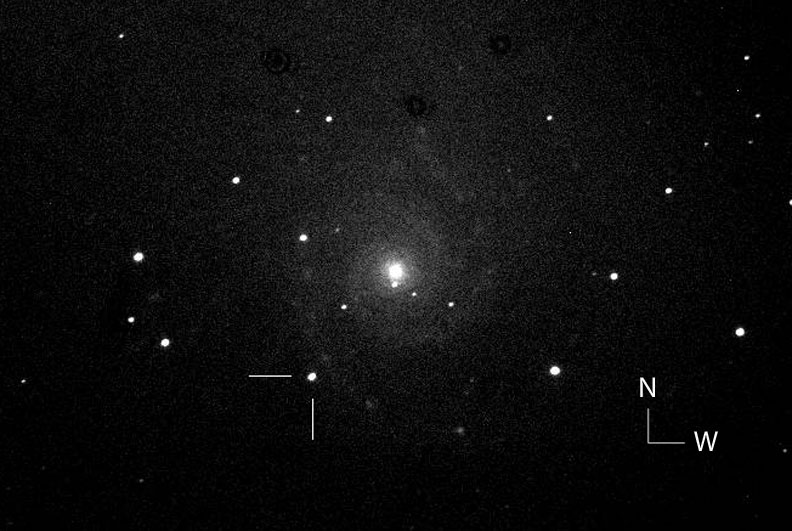

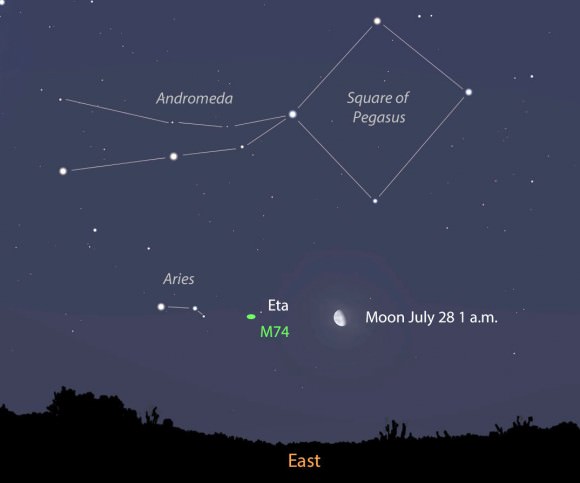

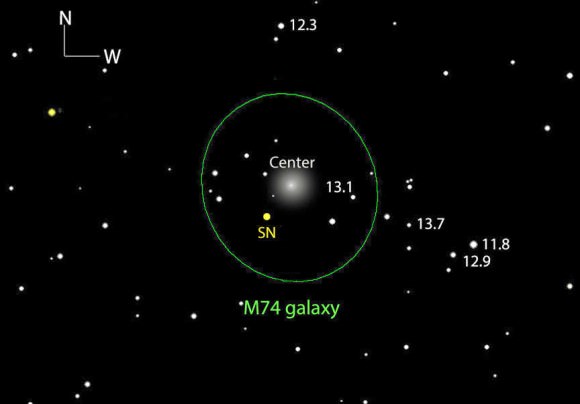

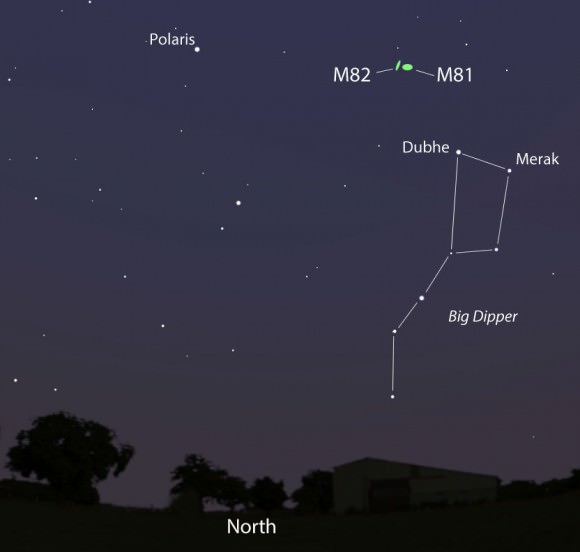

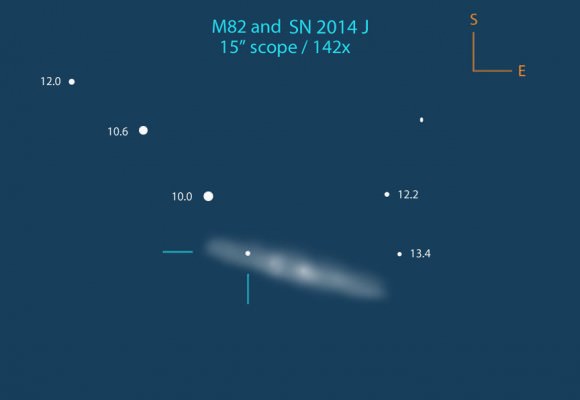

I know you’re as excited as I am to get a look at this spectacular new star the next clear night, so I’ve prepared a couple maps to help you find the galaxy. The best time to see the supernova is as soon as the sky gets dark when it’s already up in the northeastern sky above the Dipper Bowl, but since it’s circumpolar for mid-latitude observers, you can check it out any time of night.

My maps show its position for around 8 o’clock. When you dial in the galaxy in your telescope, look for a starry point along its long axis west and south of the nucleus. All the fury of this fantastic blast is concentrated in that meek spark of light glimmering in the galactic haze.

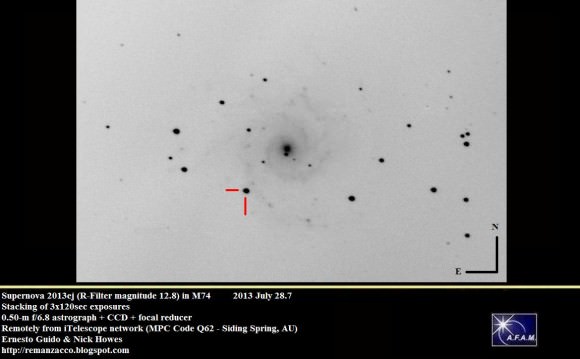

Good luck and enjoy watching one of the biggest show of fireworks the universe has to offer. We’ll keep you posted with the latest updates right here. For more photos and additional information, please see David Bishop’s excellent Latest Supernovae site. For charts with magnitudes to follow the supernova’s progress, visit the AAVSO’s Variable Star Plotter and type in ‘PSN J09554214+6940260’ for the star’s name. You can read more about the followup work by the Remanzacco Observatory team here.

UPDATE: Fraser and team from the Virtual Star Party actually imaged M82 on Sunday evening, and you can see it in the video below at the 22 minute mark. It really looks like a bright spot is showing up — and that’s about a day before it was announced. Did they catch it? In the video the galaxy appears upside down as compared to the images here:

UT reader Andrew Symes took a screenshot from the VSP, flipped it, and compared it with photo from Meineko Sakura from the Tao Astronomical Observatory it really appears the team caught the supernova before it was actually announced! Take a look: