[/caption]

Located on the Chajnantor plateau in the foothills of the Chilean Andes, ESO’s APEX telescope has been busy looking into deep, deep space. Recently a group of astronomers released their findings regarding massive galaxies in connection with extreme times of star formation in the early Universe. What they found was a sharp cut-off point in stellar creation, leaving “massive – but passive – galaxies” filled with mature stars. What could cause such a scenario? Try the materialization of a supermassive black hole…

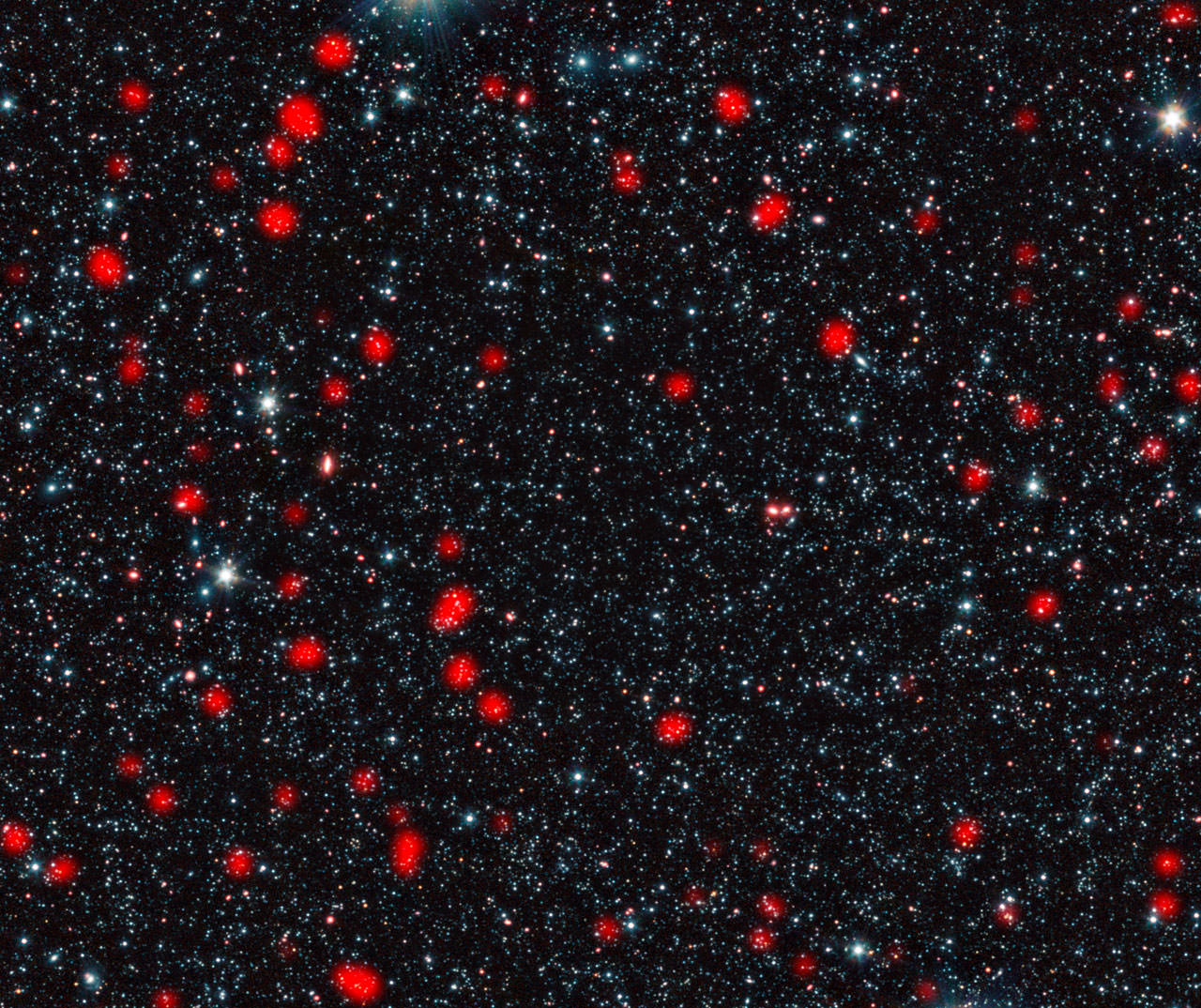

By integrating data taken with the LABOCA camera on the ESO-operated 12-metre Atacama Pathfinder Experiment (APEX) telescope with measurements made with ESO’s Very Large Telescope, NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope and other facilities, astronomers were able to observe the relationship of bright, distant galaxies where they form into clusters. They found that the density of the population plays a major role – the tighter the grouping, the more massive the dark matter halo. These findings are the considered the most accurate made so far for this galaxy type.

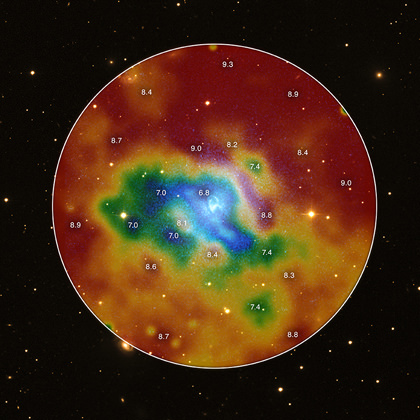

Located about 10 billion light years away, these submillimetre galaxies were once home to starburst events – a time of intense formation. By obtaining estimations of dark matter halos and combining that information with computer modeling, scientists are able to hypothesize how the halos expanding with time. Eventually these once active galaxies settled down to form giant ellipticals – the most massive type known.

“This is the first time that we’ve been able to show this clear link between the most energetic starbursting galaxies in the early Universe, and the most massive galaxies in the present day,” says team leader Ryan Hickox of Dartmouth College, USA and Durham University, UK.

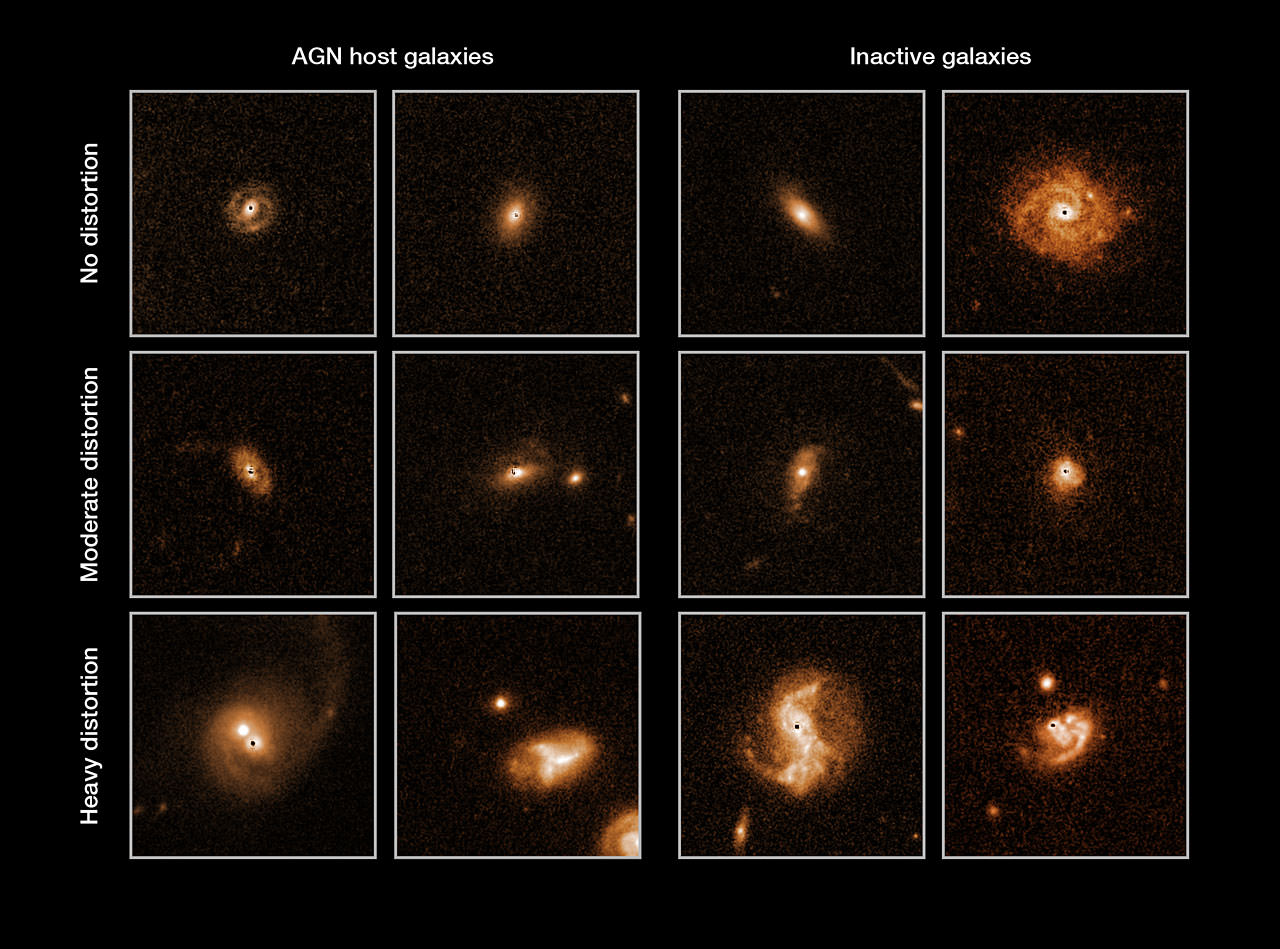

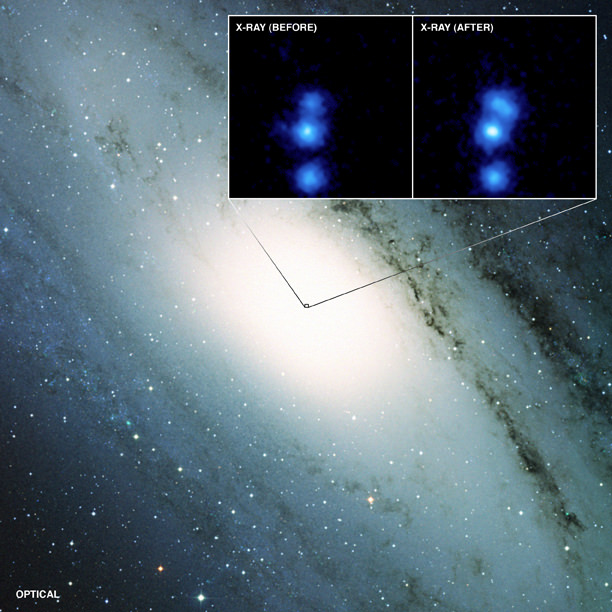

However, that’s not all the new observations have uncovered. Right now there’s speculation the starburst activity may have only lasted around 100 million years. While this is a very short period of cosmological time, this massive galactic function was once capable of producing double the amount of stars. Why it should end so suddenly is a puzzle that astronomers are eager to understand.

“We know that massive elliptical galaxies stopped producing stars rather suddenly a long time ago, and are now passive. And scientists are wondering what could possibly be powerful enough to shut down an entire galaxy’s starburst,” says team member Julie Wardlow of the University of California at Irvine, USA and Durham University, UK.

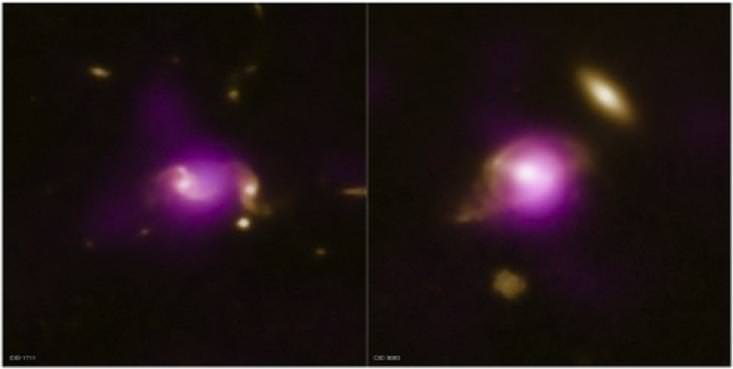

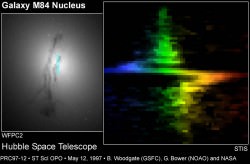

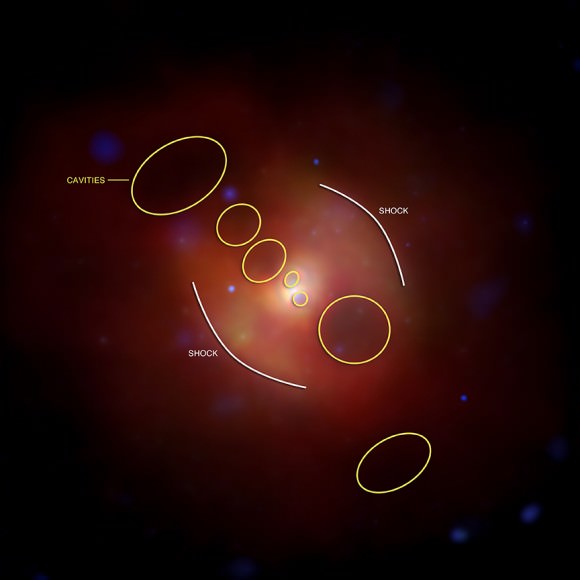

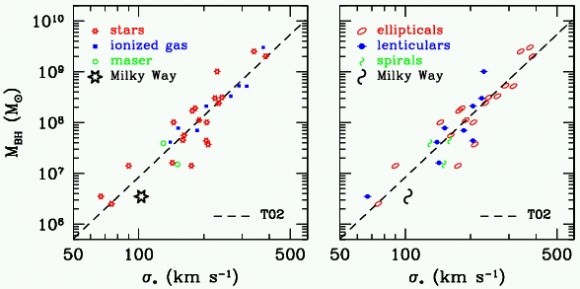

Right now the team’s findings are offering up a new solution. Perhaps at one point in cosmic history, starburst galaxies may have clustered together similar to quasars… locating themselves in the same dark matter halos. As one of the most kinetic forces in our Universe, quasars release intense radiation which is reasoned to be fostered by central black holes. This new evidence suggests intense starburst activity also empowers the quasar by supplying copious amounts of material to the black hole. In response, the quasar then releases a surge of energy which could eradicate the galaxy’s leftover gases. Without this elemental fuel, stars can no longer form and the galaxy growth comes to a halt.

“In short, the galaxies’ glory days of intense star formation also doom them by feeding the giant black hole at their centre, which then rapidly blows away or destroys the star-forming clouds,” explains team member David Alexander from Durham University, UK.

Original Story Source: European Southern Observatory News. For Further Reading: Research Paper Link.