Massive stars can devastate their surroundings, unleashing hot winds and blasting radiation. With a mass over 100 times heavier than the Sun and a luminosity a million times brighter than the Sun, Eta Carinae clocks in as one of the biggest and brightest stars in our galaxy.

The enigmatic object walks a thin line between stellar stability and tumultuous explosions. But now a team of international astronomers is growing concerned that it’s leaning toward instability and eruption.

In the 19th Century the star mysteriously threw off unusually bright light for two decades in an event that became known as the “Great Eruption,” the causes of which are still up for debate. John Herschel and others watched as Eta Carinae’s brightness oscillated around that of Vega — rivaling a supernova explosion.

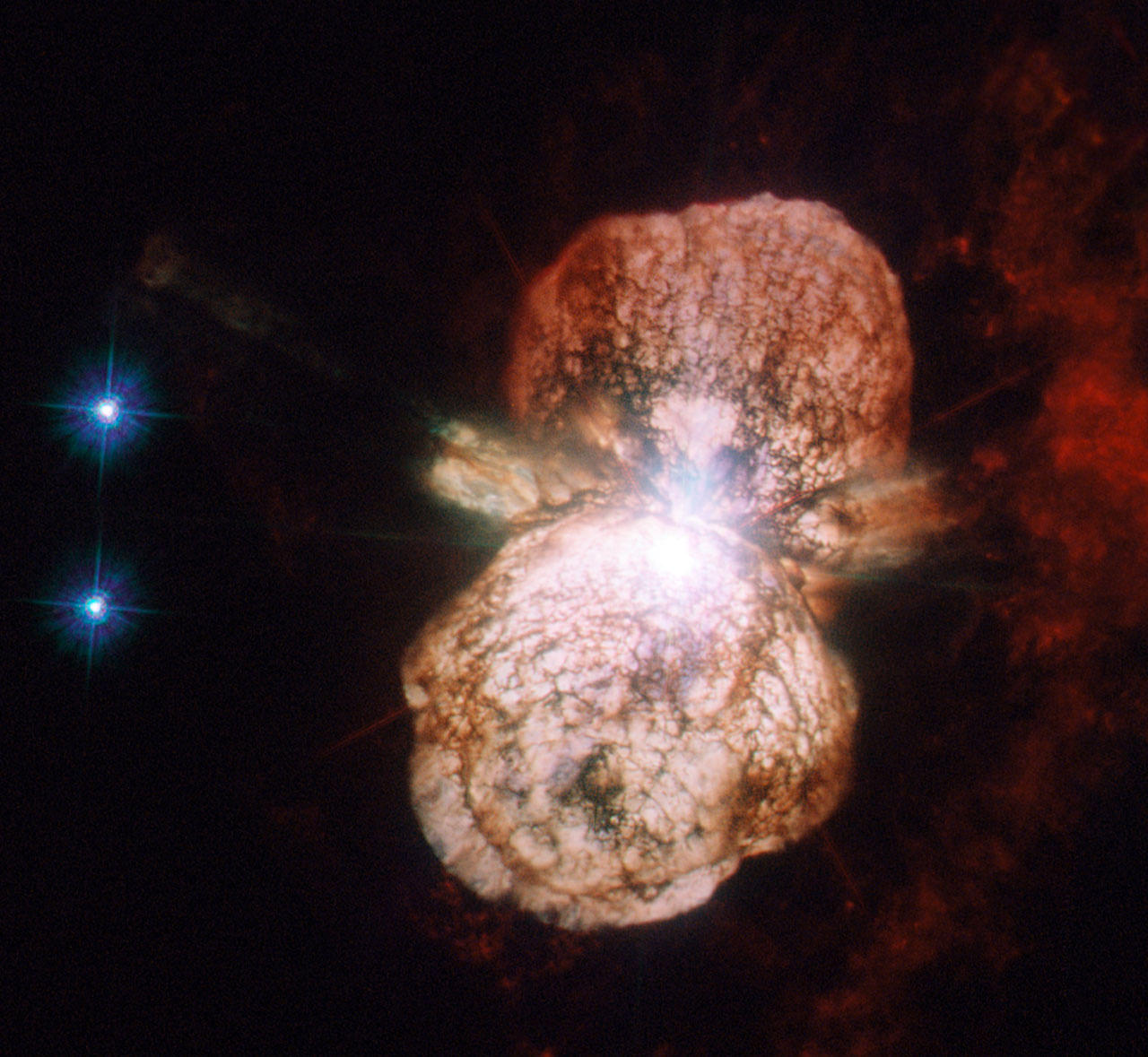

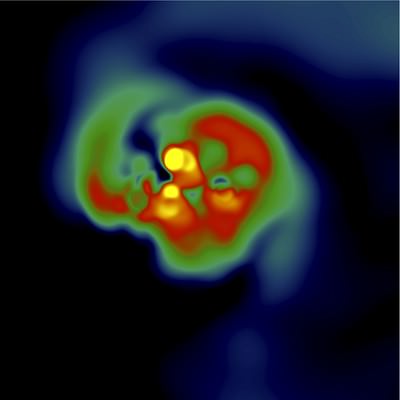

We now know the star ejected material in the form of two big globes. “During the eruption the star threw off more than 10 solar masses, which can now be observed as the surrounding bipolar nebula,” said lead author Dr. Andrea Mehner from the European Southern Observatory. Miraculously the star survived, but the nebula has been expanding into space ever since.

Eta Carinae has been observed at the South African Astronomical Observatory — a 0.75m telescope outside of Cape Town — for more than 40 years, providing a wealth of data. From the start of observations in 1976 until 1998, astronomers saw an increase across the J, H, K and L bands — filters, which allow certain wavelength ranges of infrared light to pass through.

“This data set is unique for its consistency over a timespan of more than 40 years,” Mehner told Universe Today. “It provides us with the opportunity to analyze long-term changes in the system as Eta Carinae still recovers from its Great Eruption.”

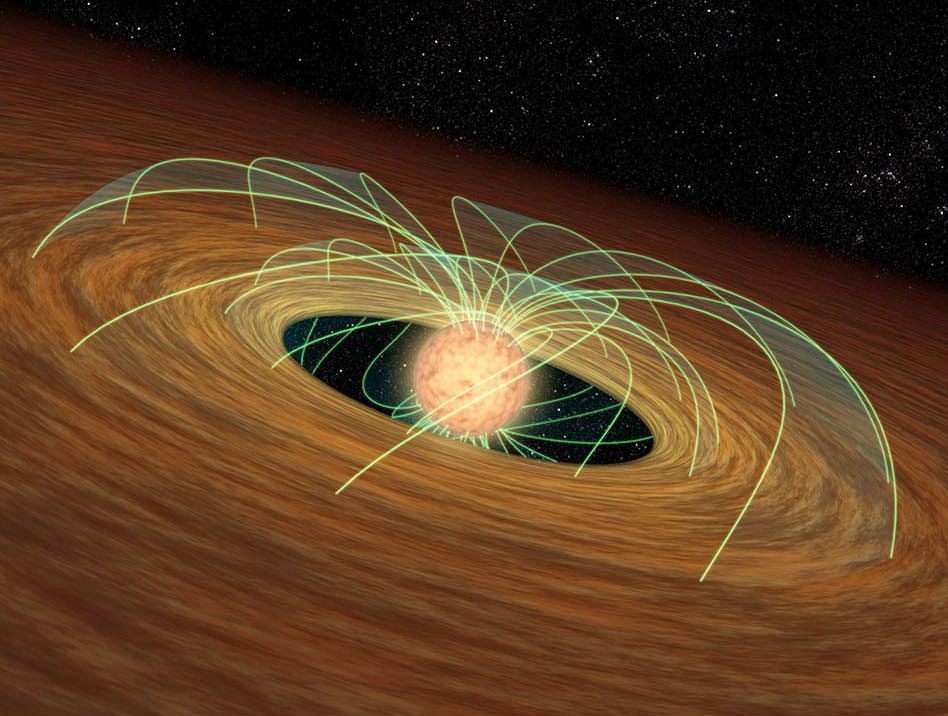

In order to understand the longterm overall increase in light we have to look at a more recent discovery noted in 2005 when scientists discovered that Eta Carinae is actually two stars: a massive blue star and a smaller companion. The temperature increased for 15 years until the companion came very close to the massive star, reaching periastron.

This increase in brightness is likely due to an overall increase in temperature of some component of the Eta Carinae system (which includes the massive blue star, its smaller companion, and the shells of gas and dust that now enshroud the system).

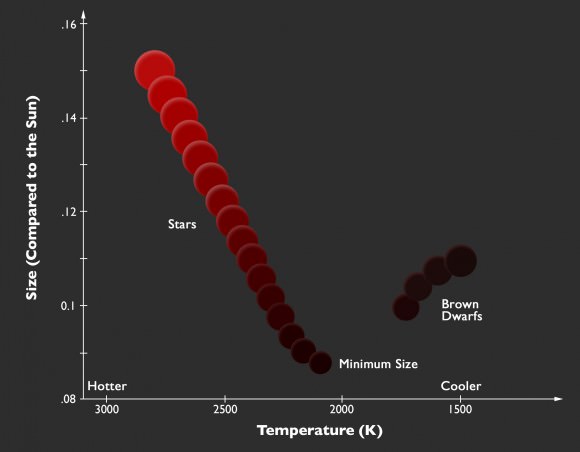

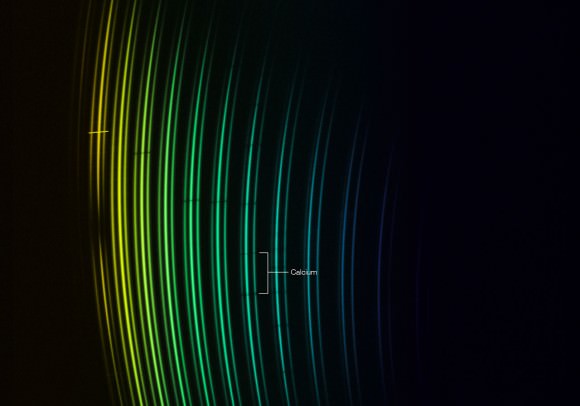

After 1998, however, the linear trend changed significantly and the star’s brightness increased much more rapidly in the J and H bands. It’s getting bluer, which in astronomy, typically means it’s getting hotter.

However, it’s unlikely the star itself is getting hotter. Instead we are seeing the effect of dust around the star being destroyed rapidly. Dust absorbs blue light. So if the dust is getting destroyed, more blue light will be able to pass through the nebulous globes surrounding the system. If this is the case, then we’re really seeing the star as it truly is, without dust absorbing certain wavelengths of its light.

While the nebula is slowly expanding and the dust is therefore dissipating, the authors do not think it’s enough to account for the recent brightening. Instead Eta Carinae is likely rotating at a different speed or losing mass at a different rate. “The changes observed may imply that the star is becoming more unstable and may head towards another eruptive phase,” Mehner told Universe Today.

Perhaps Eta Carinae is heading toward another “Great Eruption.” Only time will tell. But in a field where most events occur on a timescale of millions of years, it’s a great opportunity to watch the system evolve on a human time scale. And when Eta Carinae reaches periastron in the middle of this year, tens of telescopes will be collecting its light, hoping to see a sudden turn of events that may help us explain this exotic system.

The paper has been accepted for publication in Astronomy & Astrophysics and is available for download here.