[/caption]

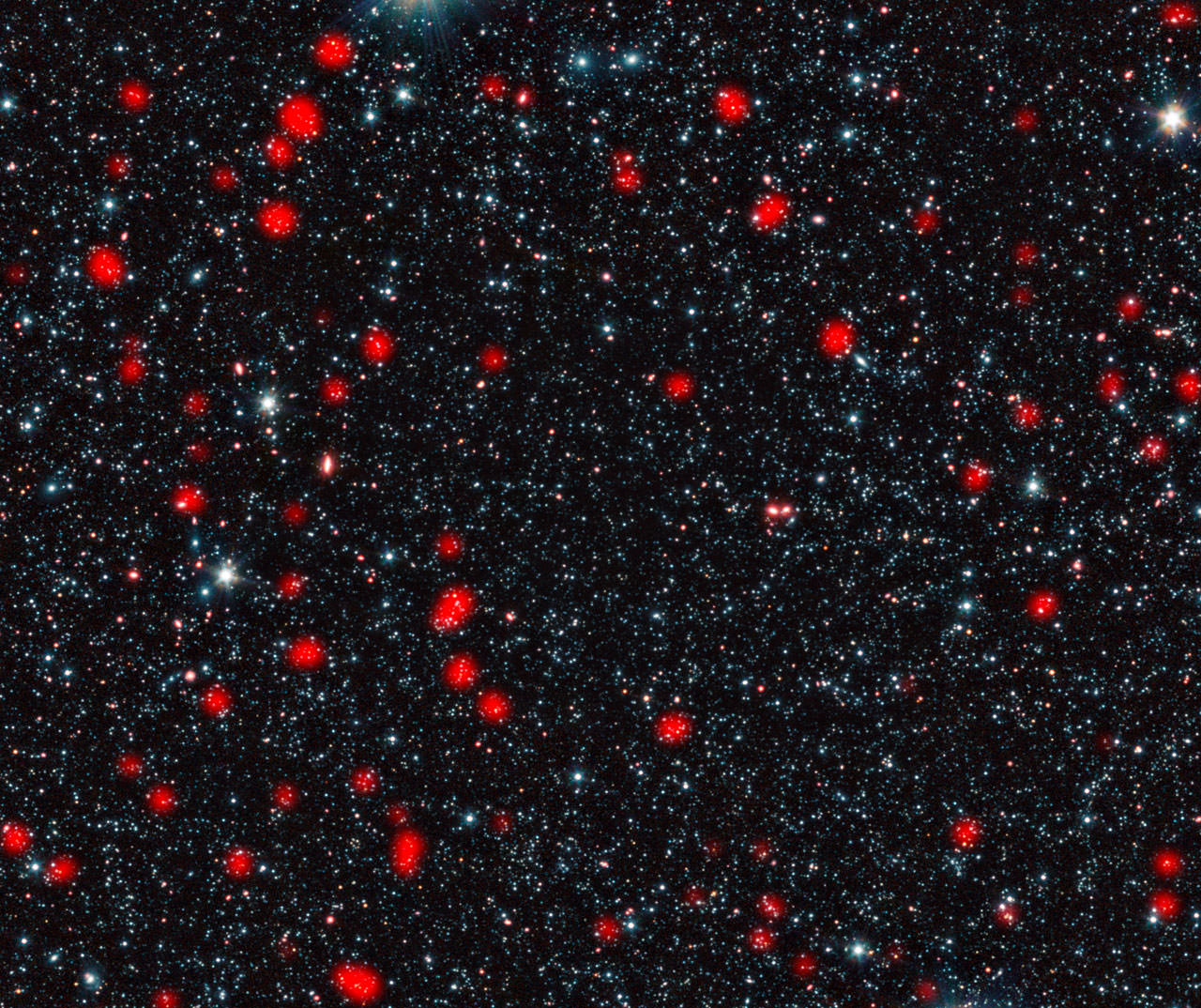

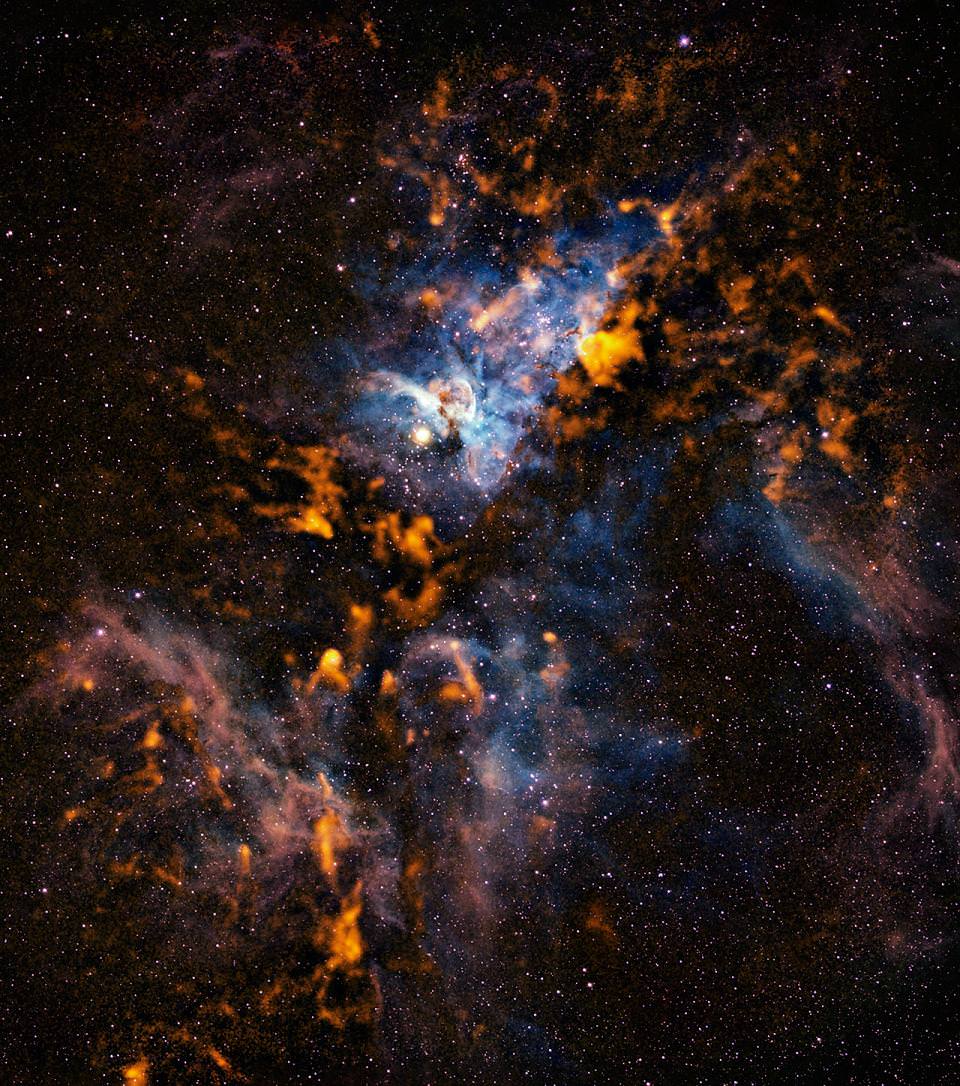

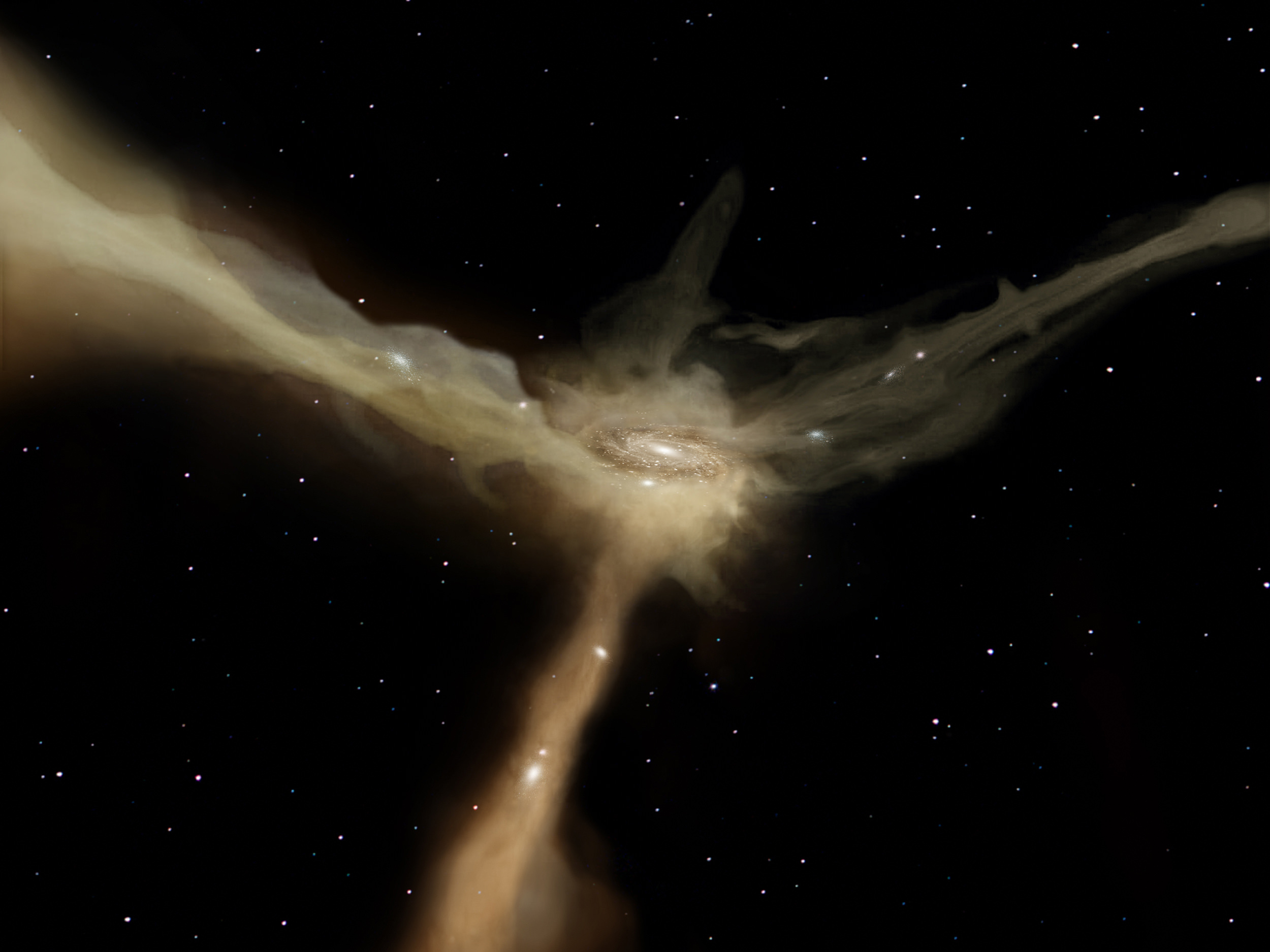

It seems logical to assume that long ago, the amount of globular clusters increased in our galaxy during star-making frenzies called ‘starbursts.’ But a new computer simulation shows just the opposite: 13 billion years ago, starbursts may have actually destroyed many of the globular clusters that they helped to create.

“It is ironic to see that starbursts may produce many young stellar clusters, but at the same time also destroy the majority of them,” said Dr. Diederik Kruijssen of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics. “This occurs not only in galaxy collisions, but should be expected in any starburst environment”

Astronomers have wondered why throughout the Universe, typical globular star clusters contain about the same number of stars. In contrast much younger stellar clusters can contain almost any number of stars, from fewer than 100 to many thousands.

The new computer simulation by Kruijssen and his team proposes that this difference could be explained by the conditions under which globular clusters formed early on in the evolution of their host galaxies.

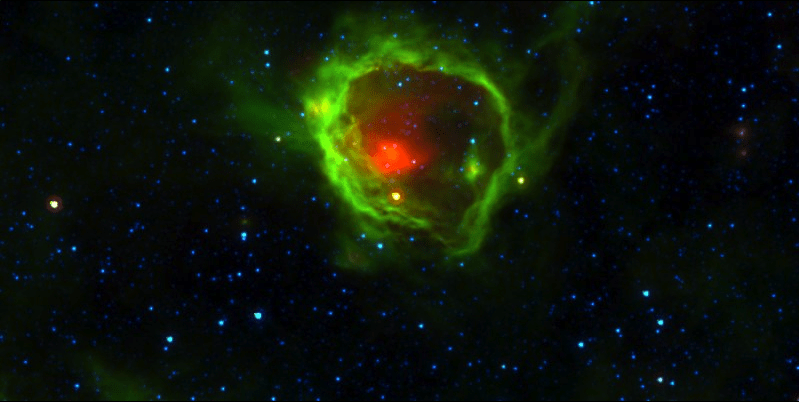

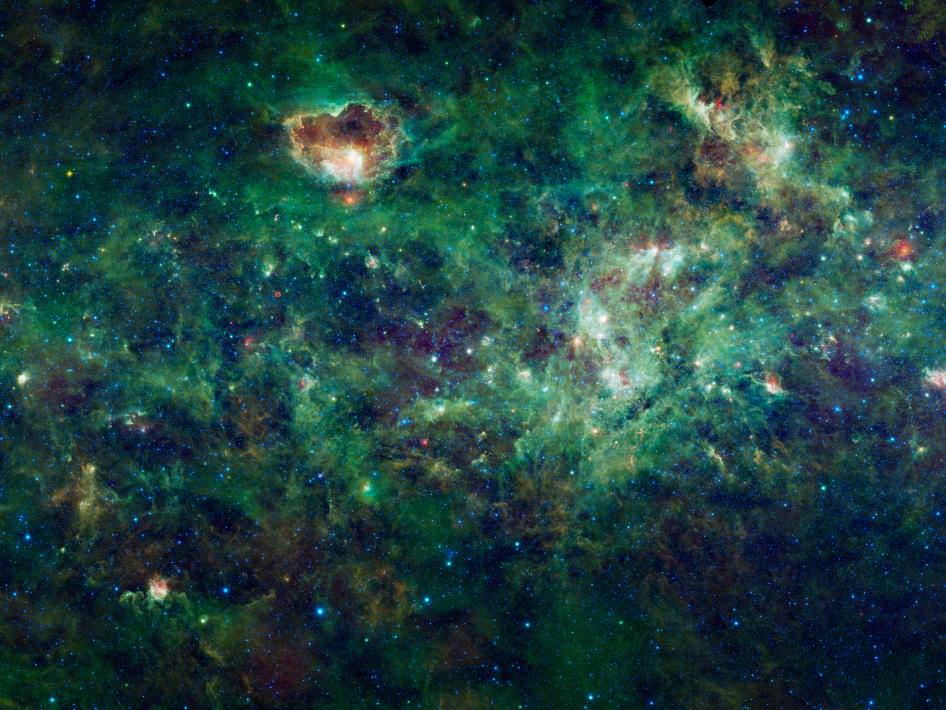

In the early Universe, starbursts were common. Large galaxies were in clusters, and collisions occurred often. The computer simulation showed that during starbursts, gas, dust and stars were still being sloshed around from the galaxy collision, with the pull of gravity on the globular clusters constantly changing. This was enough to rip apart most of the globular clusters and only the biggest ones were strong enough to survive. The simulations showed most of the star clusters were destroyed shortly after their formation, when the galactic environment was still very hostile to the young clusters. But after the environment calmed down, the surviving globular clusters have survived – now living quietly – and we can still enjoy their beauty.

In their paper, the astronomers say that this explains why the number of stars contained within globular clusters is roughly the same across the entire Universe. “It therefore makes perfect sense that all globular clusters have approximately the same large number of stars,” said Kruijssen. “Their smaller brothers and sisters that didn’t contain as many stars were doomed to be destroyed.”

Kruijssen and his team said that while the very brightest and largest clusters were capable of surviving the galaxy collision due to their own gravitational attraction, numerous smaller clusters were effectively destroyed by the rapidly changing gravitational forces.

The fact that globular clusters are comparable everywhere then indicates that the environments in which they formed were very similar, regardless of the galaxy they currently reside in. Kruijssen and his team says globular clusters can therefore be used to shed more light on how the first generations of stars and galaxies were born.

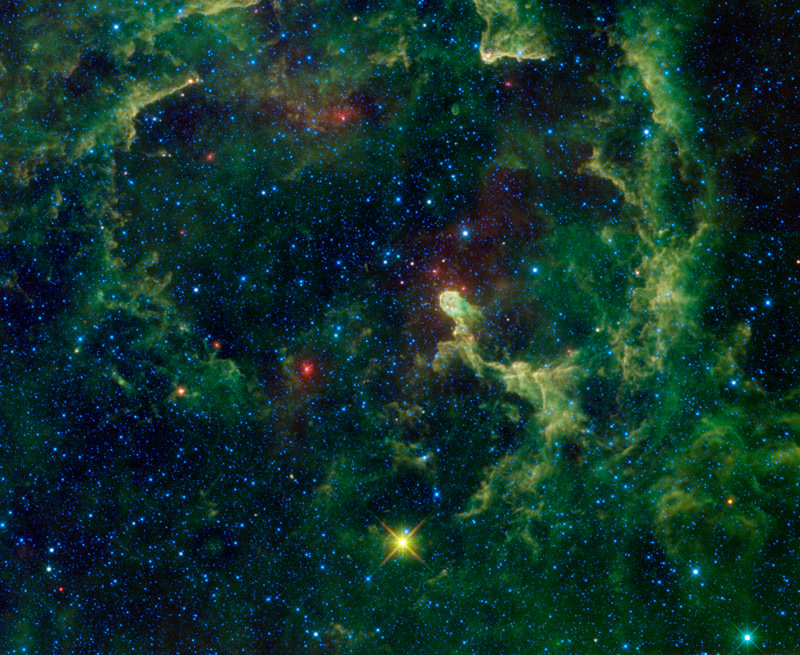

“In the nearby Universe, there are several examples of galaxies that have recently undergone large bursts of star formation,” said Kruijssen. “It should therefore be possible to see the rapid destruction of small stellar clusters in action. If this is indeed found by new observations, it will confirm our theory for the origin of globular clusters.”

This new finding may also tie in with other recent findings from Spitzer and ESO that starburst activity may have only lasted around 100 million years and may have also been cut short when black holes formed at the center of galaxies.

Source: Max-Planck Institute for Astrophysics. Paper: Kruijssen et al, “Formation versus destruction: the evolution of the star cluster population in galaxy mergers”