To the naked eye, the Sun puts out energy in a continual, steady state, unchanged through human history. (Don’t look at the sun with your naked eye!) But telescopes tuned to different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum reveal the Sun’s true nature: A shifting, dynamic ball of plasma with a turbulent life. And that dynamic, magnetic turbulence creates space weather.

Space weather is mostly invisible to us, but the part we can see is one of nature’s most stunning displays, the auroras. The aurora’s are triggered when energetic material from the Sun slams into the Earth’s magnetic field. The result is the shimmering, shifting bands of color seen at northern and southern latitudes, also known as the northern and southern lights.

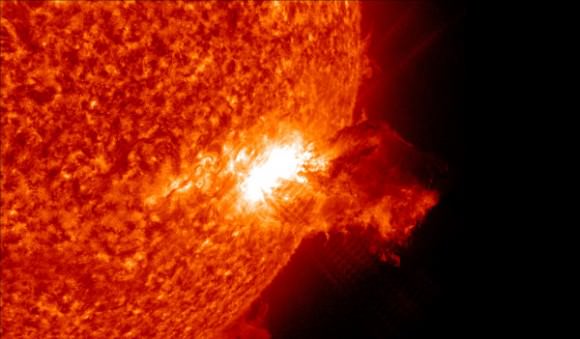

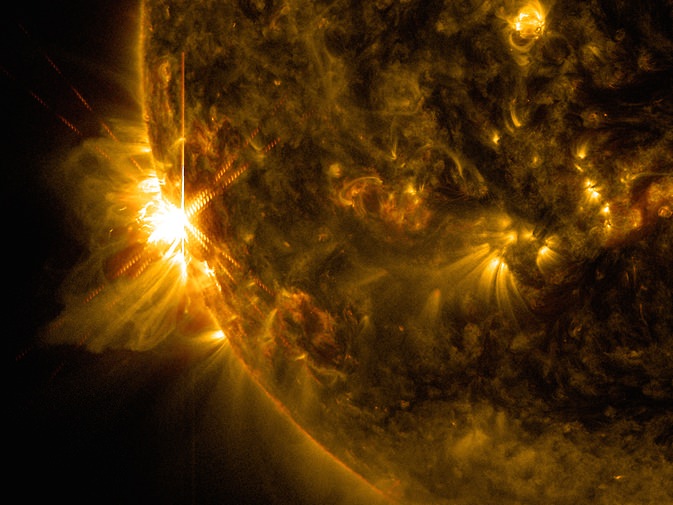

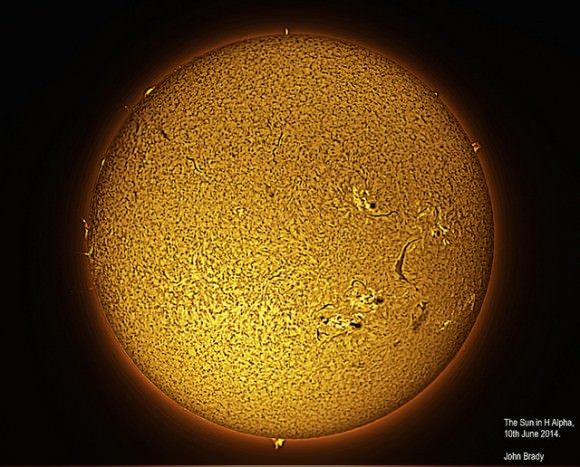

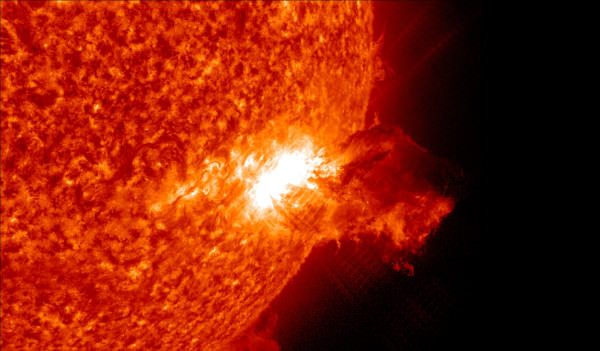

There are two things that can cause auroras, but both start with the Sun. The first involves solar flares. Highly-active regions on the Sun’s surface produce more solar flares, which are sudden, localized increase in the Sun’s brightness. Often, but not always, a solar flare is coupled with a coronal mass ejection (CME).

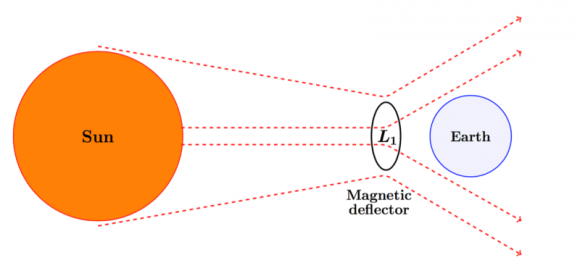

A coronal mass ejection is a discharge of matter and electromagnetic radiation into space. This magnetized plasma is mostly protons and electrons. The CME ejection often just disperses into space, but not always. If it’s aimed in the direction of the Earth, chances are we get increased auroral activity.

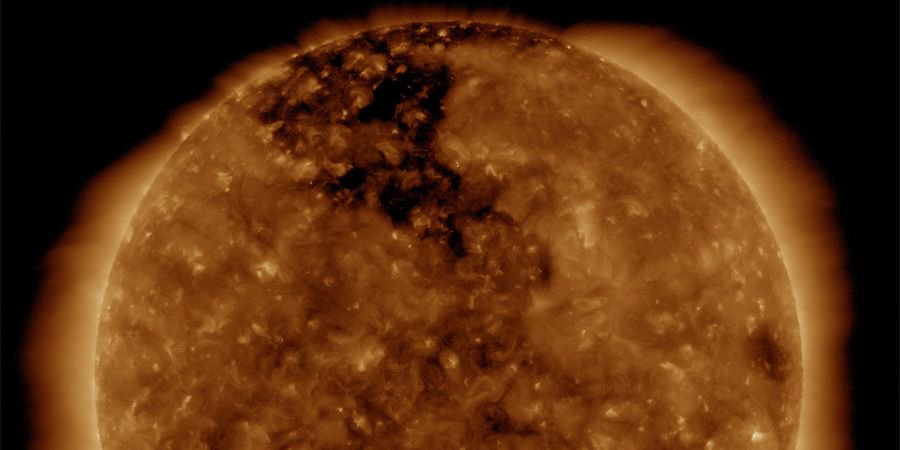

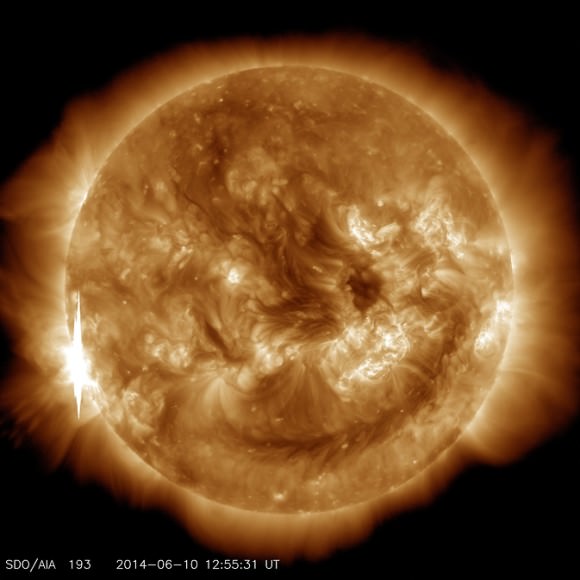

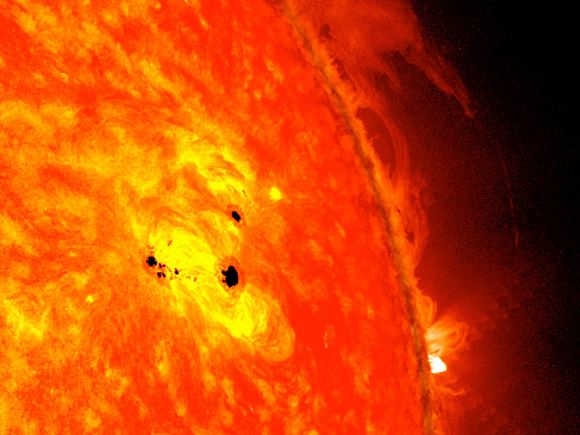

The second cause of auroras are coronal holes on the Sun’s surface. A coronal hole is a region on the surface of the Sun that is cooler and less dense than surrounding areas. Coronal holes are the source of fast-moving streams of material from the Sun.

Whether it’s from an active region on the Sun full of solar flares, or whether it’s from a coronal hole, the result is the same. When the discharge from the Sun strikes the charged particles in our own magnetosphere with enough force, both can be forced into our upper atmosphere. As they reach the atmosphere, they give up their energy. This causes constituents in our atmosphere to emit light. Anyone who has witnessed an aurora knows just how striking that light can be. The shifting and shimmering patterns of light are mesmerizing.

The auroras occur in a region called the auroral oval, which is biased towards the night side of the Earth. This oval is expanded by stronger solar emissions. So when we watch the surface of the Sun for increased activity, we can often predict brighter auroras which will be more visible in southern latitudes, due to the expansion of the auroral oval.

Something happening on the surface of the Sun in the last couple days could signal increased auroras on Earth, tonight and tomorrow (March 28th, 29th). A feature called a trans-equatorial coronal hole is facing Earth, which could mean that a strong solar wind is about to hit us. If it does, look north or south at night, depending on where your live, to see the auroras.

Of course, auroras are only one aspect of space weather. They’re like rainbows, because they’re very pretty, and they’re harmless. But space weather can be much more powerful, and can produce much greater effects than mere auroras. That’s why there’s a growing effort to be able to predict space weather by watching the Sun.

A powerful enough solar storm can produce a CME strong enough to damage things like power systems, navigation systems, communications systems, and satellites. The Carrington Event in 1859 was one such event. It produced one of the largest solar storms on record.

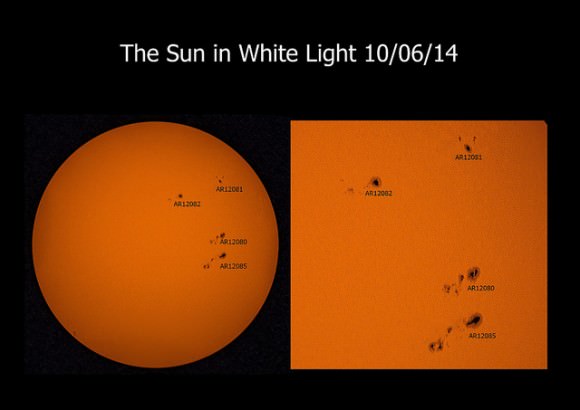

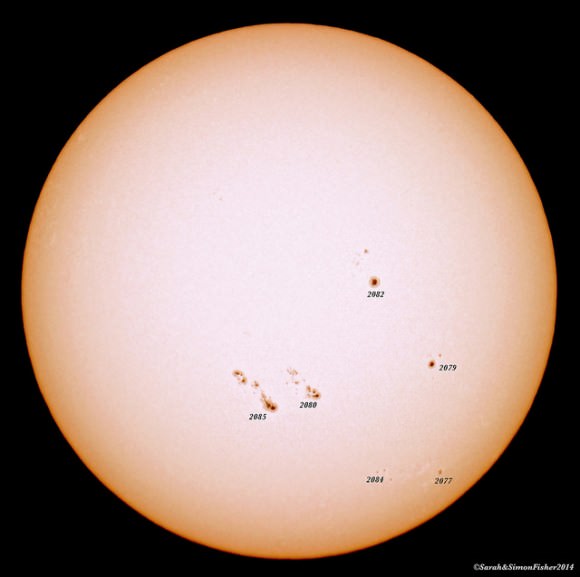

That storm occurred on September 1st and 2nd, 1859. It was preceded by an increase in sun spots, and the flare that accompanied the CME was observed by astronomers. The auroras caused by this storm were seen as far south as the Caribbean.

The same storm today, in our modern technological world, would wreak havoc. In 2012, we almost found out exactly how damaging a storm of that magnitude could be. A pair of CMEs as powerful as the Carrington Event came barreling towards Earth, but narrowly missed us.

We’ve learned a lot about the Sun and solar storms since 1859. We now know that the Sun’s activity is cyclical. Every 11 years, the Sun goes through its cycle, from solar maximum to solar minimum. The maximum and minimum correspond to periods of maximum sunspot activity and minimum sunspot activity. The 11 year cycle goes from minimum to minimum. When the Sun’s activity is at its minimum in the cycle, most CMEs come from coronal holes.

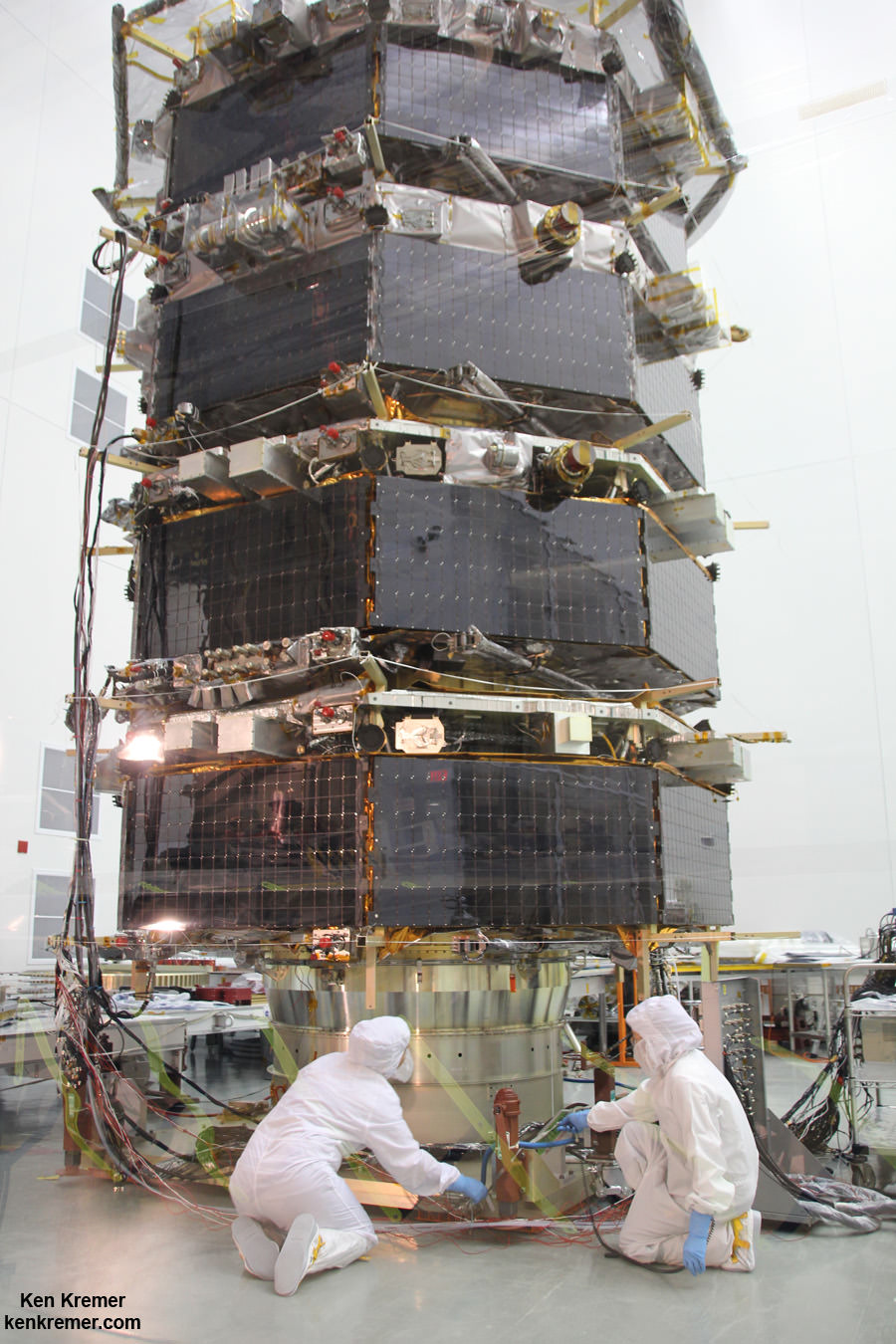

NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory (SDO), and the combined ESA/NASA Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO) are space observatories tasked with studying the Sun. The SDO focuses on the Sun and its magnetic field, and how changes influence life on Earth and our technological systems. SOHO studies the structure and behavior of the solar interior, and also how the solar wind is produced.

Several different websites allow anyone to check in on the behavior of the Sun, and to see what space weather might be coming our way. The NOAA’s Space Weather Prediction Center has an array of data and visualizations to help understand what’s going on with the Sun. Scroll down to the Aurora forecast to watch a visualization of expected auroral activity.

NASA’s Space Weather site contains all kinds of news about NASA missions and discoveries around space weather. SpaceWeatherLive.com is a volunteer run site that provides real-time info on space weather. You can even sign up to receive alerts for upcoming auroras and other solar activity.