There’s a new type of planet in town, though you won’t find it in well-aged solar systems like our own. It’s more of a stage of formation that planets like Earth can go through. And its existence helps explain the relationship between Earth and our Moon.

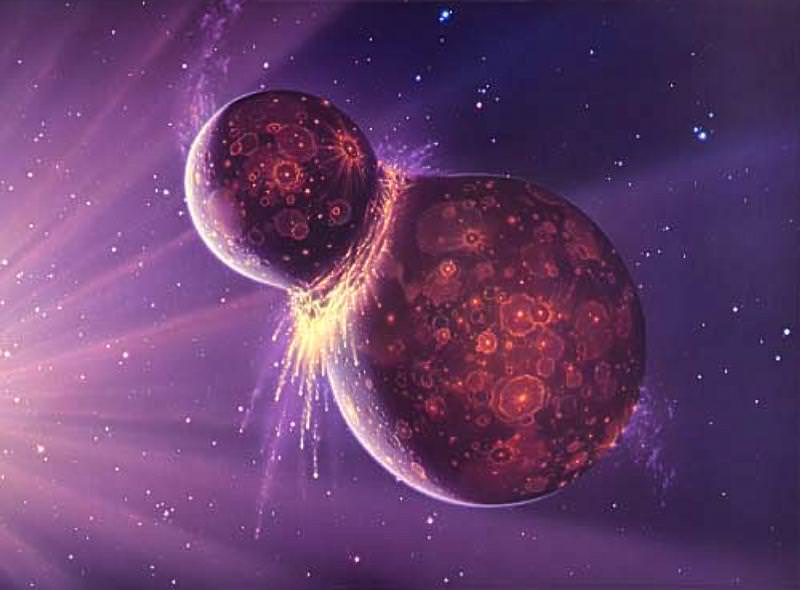

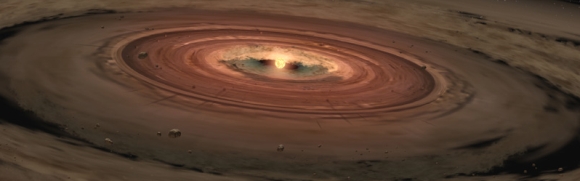

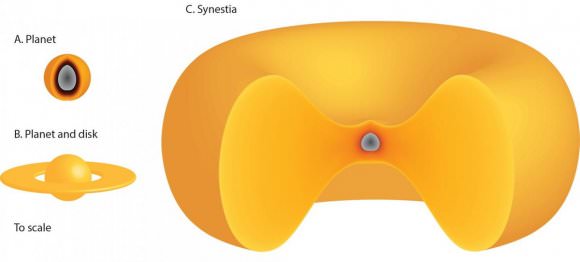

The new type of planet is a huge, spinning, donut-shaped mass of hot, vaporized rock, formed as planet-sized objects smash into each other. The pair of scientists behind the study explaining this new planet type have named it a ‘synestia.’ Simon Lock, a graduate student at Harvard University, and Sarah Stewart, a professor in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of California, Davis, say that Earth was at one time a synestia.

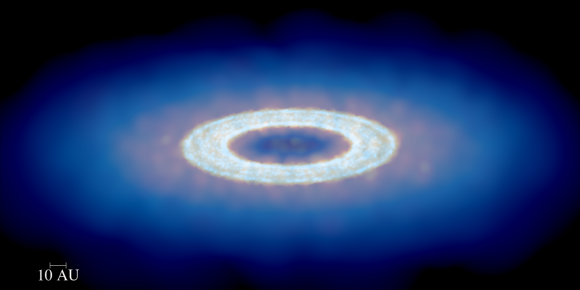

The current theory of planetary formation goes like this: When a star forms, the left-over material is in motion around the star. This left-over material is called a protoplanetary disk. The material coagulates into larger bodies as the smaller ones collide and join together.

As the bodies get larger and larger, the force of their collisions becomes greater and greater, and when two large bodies collided, their rocky material melts. Then, the newly created body cools, and becomes spherical. It’s understood that this is how Earth and the other rocky planets in our Solar System formed.

Lock and Stewart looked at this process and asked what would happen if the resulting body was spinning quickly.

When a body is spinning, the law of conservation of angular momentum comes into play. That law says that a spinning body will spin until an external torque slows it down. The often-used example from figure skating helps explain this.

If you’ve ever watched figure skaters, and who hasn’t, their actions are very instructive. When a single skater is spinning rapidly, she stretches out her arms to slow the rate of spin. When she folds her arms back into her body, she speeds up again. Her angular momentum is conserved.

This short video shows figure skaters and physics in action.

If you don’t like figure skating, this one uses the Earth to explain angular momentum.

Now take the example from a pair of figure skaters. When they’re both turning, and the two of them join together by holding each other’s hands and arms, their angular momentum is added together and conserved.

Replace two figure skaters with two planets, and this is what the two scientists behind the study wanted to model. What would happen if two large bodies with high energy and high angular momentum collided with each other?

If the two bodies had high enough temperatures and high enough angular momentum, a new type of planetary structure would form: the synestia. “We looked at the statistics of giant impacts, and we found that they can form a completely new structure,” Stewart said.

“We looked at the statistics of giant impacts, and we found that they can form a completely new structure.” – Professor Sarah Stewart, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of California, Davis.

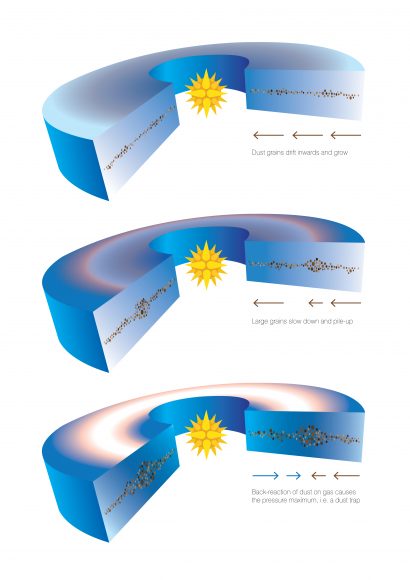

As explained in a press release from the UC Davis, for a synestia to form, some of the vaporized material from the collision must go into orbit. When a sphere is solid, every point on it is rotating at the same rate, if not the same speed. But when some of the material is vaporized, its volume expands. If it expands enough, and if its moving fast enough, it leaves orbit and forms a huge disc-shaped synestia.

Other theories have proposed that two large enough bodies could form an orbiting molten mass after colliding. But if the two bodies had high enough energy and temperature to vaporize some of the rock, the resulting synestia would occupy a much larger space.

“The main issue with looking for synestias around other stars is that they don’t last a long time. These are transient, evolving objects that are made during planet formation.” – Professor Sarah Stewart, UC Davis.

These synestias likely wouldn’t last very long. They would cool quickly and condense back into rocky bodies. For a body the size of Earth, the synestia might only last one hundred years.

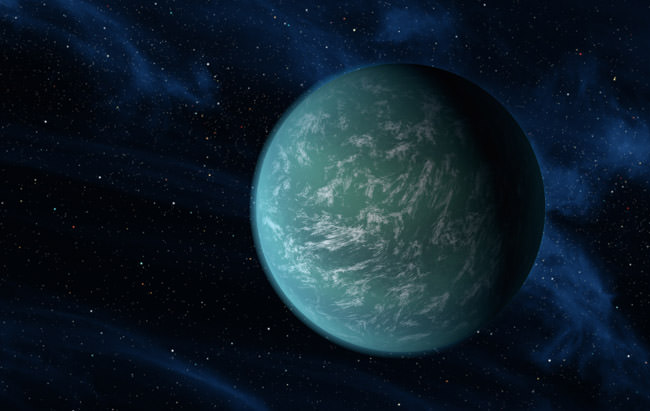

The synestia structure sheds some light on how moons are formed. The Earth and the Moon are very similar in terms of composition, so it’s likely they formed as a result of a collision. It’s possible that the Earth and Moon formed from the same synestia.

These synestias have been modelled, but they haven’t been observed. However, the James Webb Space Telescope will have the power to peer into protoplanetary disks and watch planets forming. Will it observe a synestia?

“These are transient, evolving objects that are made during planet formation.” – Professor Sarah Stewart, UC Davis

In an email exchange with Universe Today, Dr. Sarah Stewart of UC Davis, one of the scientists behind the study, told us that “The main issue with looking for synestias around other stars is that they don’t last a long time. These are transient, evolving objects that are made during planet formation.”

“So the best bet for finding a rocky synestia is young systems where the body is close to the star. For gas giant planets, they may form a synestia for a period of their formation. We are getting close to being able to image circumplanetary disks in other star systems.”

Once we have the ability to observe planets forming in their circumstellar disks, we may find that synestias are more common than rare. In fact, planets may go through the synestia stage multiple times. Dr. Stewart told us that “Based on the statistics presented in our paper, we expect that most (more than half) of rocky planets that form in a manner similar to Earth became synestias one or more times during the giant impact stage of accretion.”