We present here a compendium of Universe Today articles on comet Siding Spring. Altogether 18 Universe Today stories and counting have represented our on-going coverage of a once in a lifetime event. The articles beginning in February 2013, just days after its discovery, lead to the comet’s penultimate event – the flyby of Mars, October 19, 2014. While comet Siding Spring will reach perihelion just 6 days later, October 25, 2014, it will hardly have sensed the true power and impact that our Sun can have on a comet.

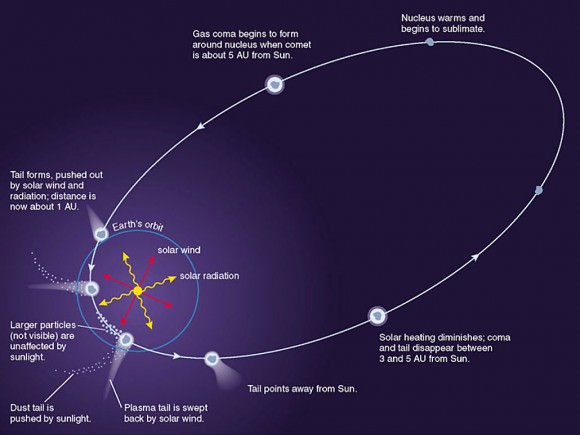

Siding Spring’s Oort Cloud cousin, Comet ISON in November 2013 encountered the Sun at a mere 1.86 million km. The intensity of the Sun’s glare was 12,600 times greater than what Siding Spring will experience in a few days. Comet ISON did not survive its passage around the Sun but Comet Siding Spring will soon turn back and begin a very long journey to its place of origin, the Oort Cloud far beyond Pluto.

The closest approach for comet Siding Spring with the Sun – perihelion is at a distance of 1.39875 Astronomical Units (1 AU being the distance between the Earth and Sun), still 209 million km (130 million miles). The exact period of the comet is not exactly known but it is measured in millions of years. In my childhood astronomy book, it stated that comet Halley, when it is at its furthest distance from the Sun, is moving no faster than a galloping horse. This has also been all that comet Siding Spring could muster for millions of years – the slightest of movement in the direction of the Sun.

It is only in the last 3 years, out all the millions spent on its journey, that it has felt the heat of the Sun and been in proximity to the planetary bodies of our Solar System. This is story of all long period comets. A video camera on Siding Spring would have recorded the emergence and evolution of one primate out of several, one that left the trees to stand on two legs, whose brain grew in size and complexity and has achieved all the technological wonders (and horrors) we know of today.

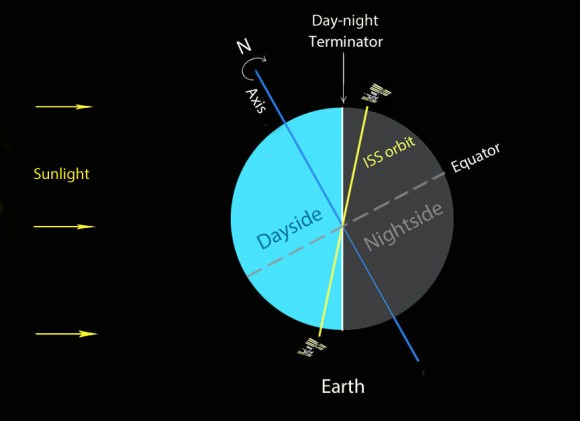

Now with its close encounter with Mars, the planet’s gravity will bend the trajectory of the comet and reduce its orbital period to approximately one million years. No one will be waiting up late for its next return to the inner Solar System.

It is also unknown what force in the depths of the Oort cloud nudged the comet into its encounter with Mars and the Sun. Like the millions of other Oort cloud objects, Siding Spring has spent its existence – 4.5 Billion years, in the darkness of deep space, with its parent star, the Sun, nothing more than a point of light, the brightest star in its sky. The gravitational force that nudged it may have been a passing star, another cometary body or possibly a larger trans-Neptunian object the size of Pluto and even as large as Mars or the Earth.

The forces of nature on Earth cause a constant turning over geological features. Our oceans and atmosphere are constantly recycling water and gases. The comets that we receive from the Oort Cloud are objects as old as our Solar System. Yet it is the close encounter with Mars that has raised the specter of an otherwise small ordinary comet. All these comets from deep space are fascinating gems nearly unaltered for 1/3rd of the time span of the known Universe.

Universe Today’s Siding Spring Compendium

2014/10/17: Here’s A Look At Comet Siding Spring Two Days Before Its Encounter With Mars

2014/10/17: Weekly Space Hangout Oct 17 2014

2014/10/15: Comet A1 Siding Spring vs Mars Views In Space And Time

2014/10/10: How To See Comet Siding Spring As It Encounters Mars

2014/10/08: Comet Siding Spring Close Call For Mars Wake Up Call For Earth

2014/09/19: How NASA’s Next Mars Spacecraft Will Greet The Red Planet On Sunday

2014/09/09: Tales Tails Of Three Comets

2014/08/30: Caterpillar Comet Poses For Pictures En Route To Mars

2014/07/26: NASA Preps For Nail Biting Comet Flyby Of Mars

2014/05/08: Interesting Prospects For Comet A1 Siding Spring Versus The Martian Atmosphere

2014/03/27: Mars Bound Comet Siding Spring Sprouts Multiple Jets

2014/01/29: Neowise Spots Mars Crossing Comet

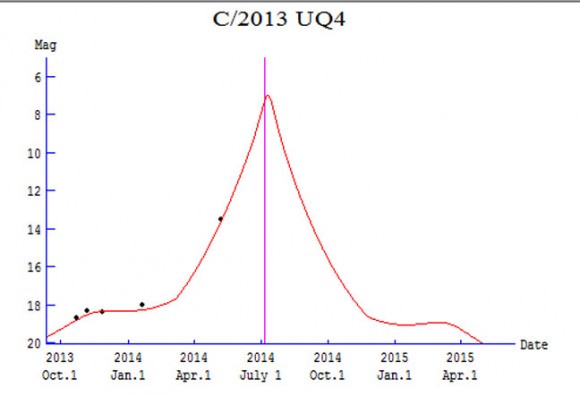

2014/01/02: Comets Prospects For 2014 A Look Into The Crystal Ball

2013/04/12: New Calculations Effectively Rule Out Comet Impacting Mars In 2014

2013/03/28: NASA Scientists Discuss Potential Comet Impact On Mars

2013/03/05: Update On The Comet That Might Hit Mars

2013/02/26: Is A Comet On A Collision Course With Mars