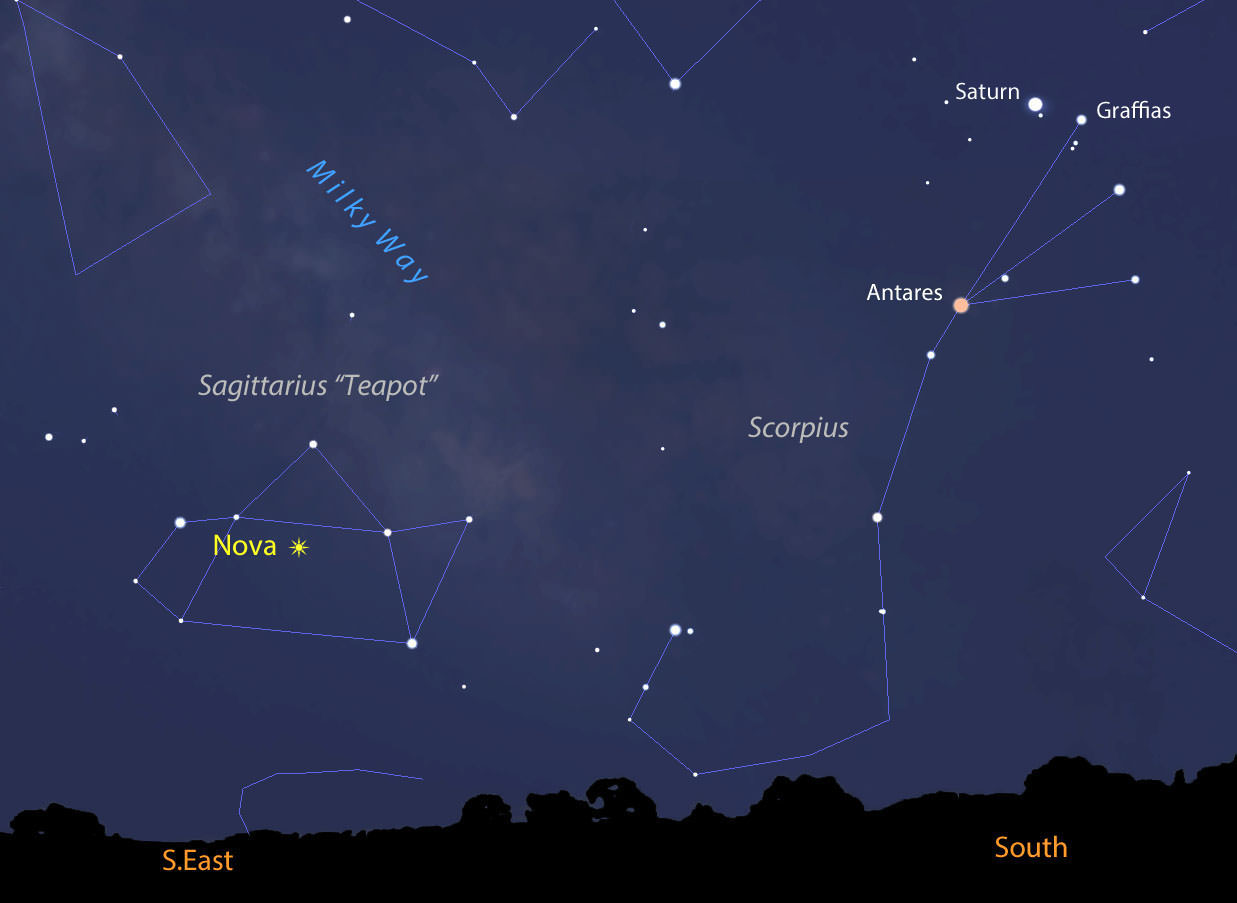

Looks like the Sagittarius Teapot’s got a new whistle. On March 15, John Seach of Chatsworth Island, NSW, Australia discovered a probable nova in the heart of the constellation using a DSLR camera and fast 50mm lens. Checks revealed no bright asteroid or variable star at the location. At the time, the new object glowed at the naked eye limit of magnitude +6, but a more recent observation by Japanese amateur Koichi Itagaki puts the star at magnitude +5.3, indicating it’s still on the rise.

A 5th magnitude nova’s not too difficult to spot with the naked eye from a dark sky, and binoculars will show it with ease. Make a morning of it by setting up your telescope for a look at Saturn and the nearby double star Graffias (Beta Scorpii), one of the prettiest, low-power doubles in the summer sky.

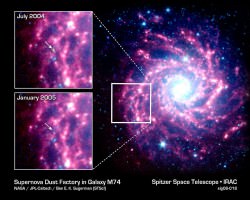

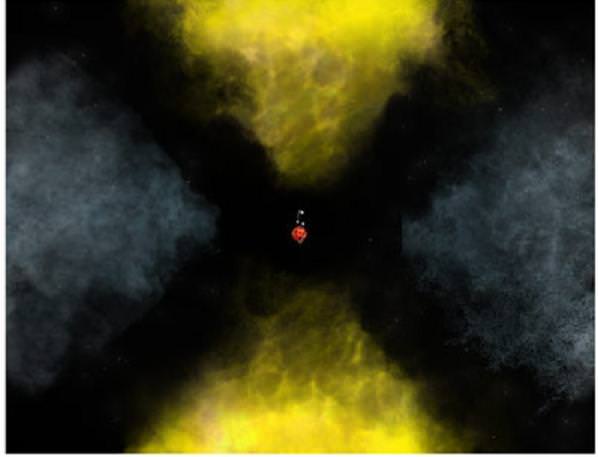

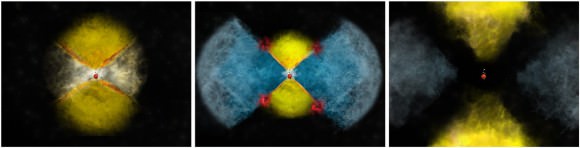

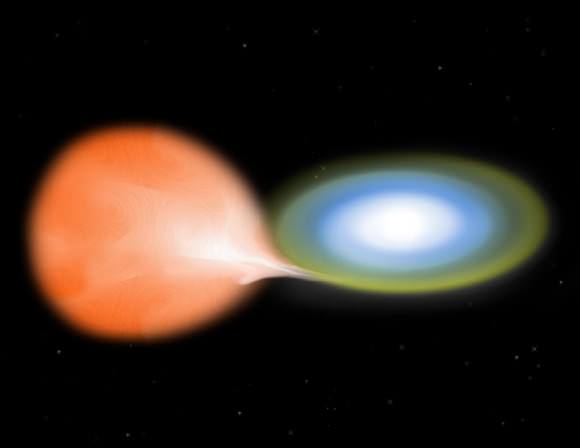

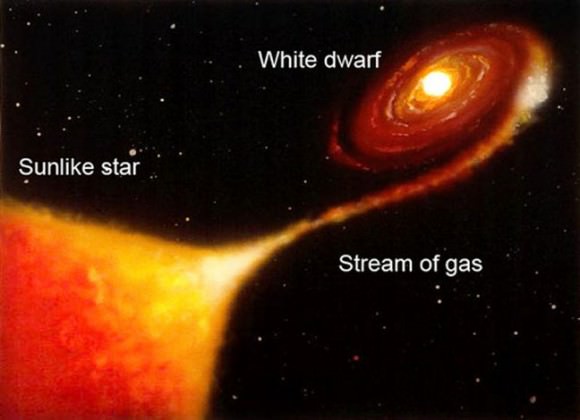

Nova means “new”, but novae aren’t fresh stars coming to life but an explosion occurring on the surface of an otherwise faint star no one’s taken notice of – until the blast causes it to brighten 50,000 to 100,000 times. A nova occurs in a close binary star system, where a small but extremely dense and massive (for its size) white dwarf siphons hydrogen gas from its closely orbiting companion. After swirling about in a disk around the dwarf, it’s funneled down to the star’s 150,000 F° surface where gravity compacts and heats the gas until detonates in a titanic thermonuclear explosion. Suddenly, a faint star that wasn’t on anyone’s radar vaults a dozen magnitudes to become a standout “new star”.

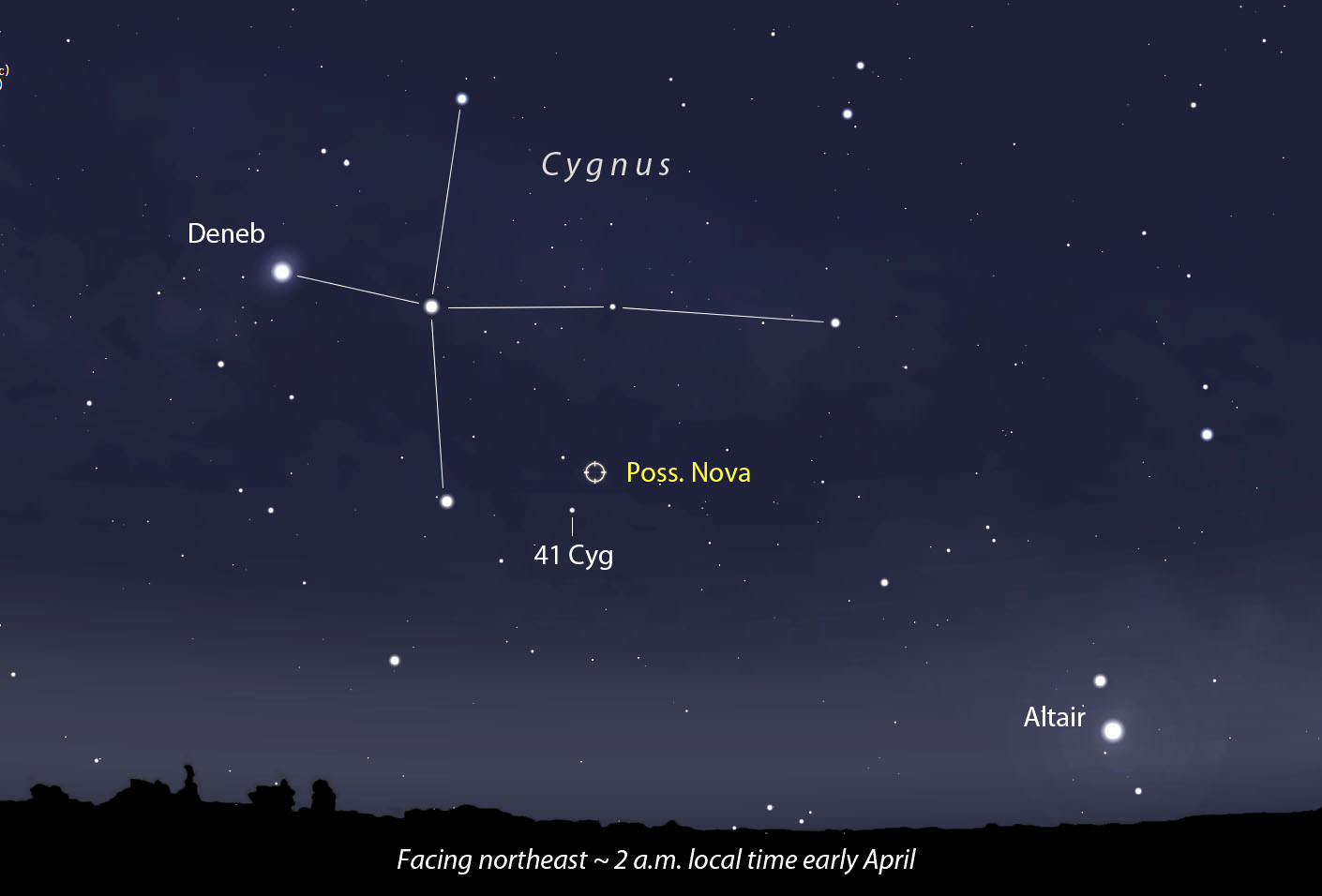

Regular nova observers may wonder why so many novae are discovered in the Sagittarius-Scorpius Milky Way region. There are so many more stars in the dense star clouds of the Milky Way, compared to say the Big Dipper or Canis Minor, that the odds go up of seeing a relatively rare event like a stellar explosion is likely to happen there than where the stars are scattered thinly. Given this galactic facts of life, that means most of will have to set our alarms to spot this nova. Sagittarius doesn’t rise high enough for a good view until the start of morning twilight. For the central U.S., that’s around 5:45-6 a.m.

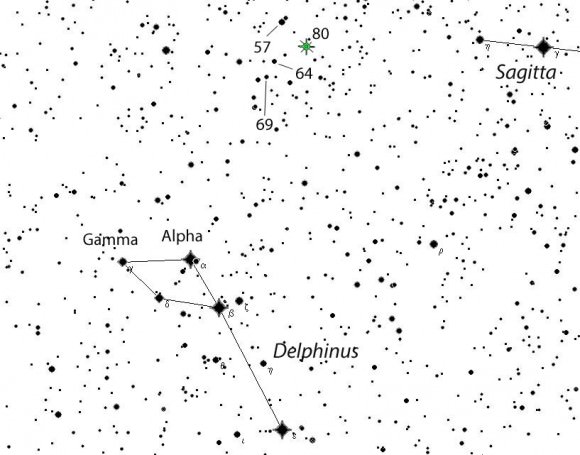

Find a location with a clear view to the southeast and get oriented at the start of morning twilight or about 100 minutes before sunrise. Using the maps, locate Sagittarius below and to the east (left) of Scorpius. Once you’ve arrived, point your binoculars into the Teapot and star-hop to the nova’s location. I’ve included visual magnitudes of neighboring stars to help you estimate the nova’s brightness and track its changes in the coming days and weeks.

Whether it continues to brighten or soon begins to fade is anyone’s guess at this point. That only makes going out and seeing it yourself that much more enticing.

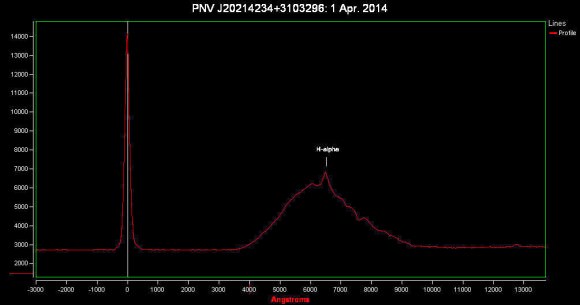

UPDATE: A spectrum of the object was obtained with the Liverpool Telescope March 16 confirming that the “new star” is indeed a nova. Gas has been clocked moving away from the system at more than 6.2 million mph (10 million kph)!