[/caption]

It’s been a tenet of the standard model of physics for over a century. The speed of light is a unwavering and unbreakable barrier, at least by any form of matter and energy we know of. Nothing in our Universe can travel faster than 299,792 km/s (186,282 miles per second), not even – as the term implies – light itself. It’s the universal constant, the “c” in Einstein’s E = mc2, a cosmic speed limit that can’t be broken.

That is, until now.

An international team of scientists at the Gran Sasso research facility outside of Rome announced today that they have clocked neutrinos traveling faster than the speed of light. The neutrinos, subatomic particles with very little mass, were contained within beams emitted from CERN 730 km (500 miles) away in Switzerland. Over a period of three years, 15,000 neutrino beams were fired from CERN at special detectors located deep underground at Gran Sasso. Where light would have made the trip in 2.4 thousandths of a second, the neutrinos made it there 60 nanoseconds faster – that’s 60 billionths of a second – a tiny difference to us but a huge difference to particle physicists!

The implications of such a discovery are staggering, as it would effectively undermine Einstein’s theory of relativity and force a rewrite of the Standard Model of physics.

“We are shocked,” said project spokesman and University of Bern physicist Antonio Ereditato.

“We have high confidence in our results. We have checked and rechecked for anything that could have distorted our measurements but we found nothing. We now want colleagues to check them independently.”

Neutrinos are created naturally from the decay of radioactive materials and from reactions that occur inside stars. Neutrinos are constantly zipping through space and can pass through solid material easily with little discernible effect… as you’ve been reading this billions of neutrinos have already passed through you!

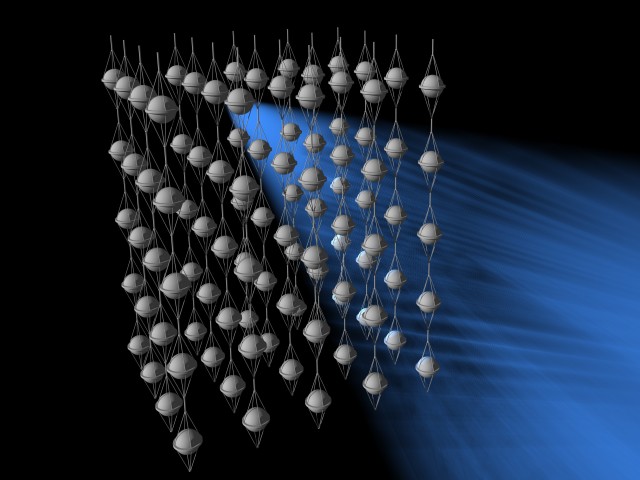

The experiment, called OPERA (Oscillation Project with Emulsion-tRacking Apparatus) is located in Italy’s Gran Sasso facility 1,400 meters (4,593 feet) underground and uses a complex array of electronics and photographic plates to detect the particle beams. Its subterranean location helps prevent experiment contamination from other sources of radiation, such as cosmic rays. Over 750 scientists from 22 countries around the world work there.

Ereditato is confident in the results as they have been consistently measured in over 16,000 events over the past two years. Still, other experiments are being planned elsewhere in an attempt to confirm these remarkable findings. If they are confirmed, we may be looking at a literal breakdown of the modern rules of physics as we know them!

“We have high confidence in our results,” said Ereditato. “We have checked and rechecked for anything that could have distorted our measurements but we found nothing. We now want colleagues to check them independently.”

A preprint of the OPERA results will be posted on the physics website ArXiv.org.

Read more on the Nature article here and on Reuters.com.

UPDATE: The OPERA team paper can be found here.