A little over a week before NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft fired its rockets to successfully enter orbit around Mars, MESSENGER performed a little burn of its own – the second of four orbit correction maneuvers (OCMs) that will allow it to remain in orbit around Mercury until next March. Although it is closing in on the end of its operational life it’s nice to know we still have a few more months of images and discoveries from MESSENGER to look forward to!

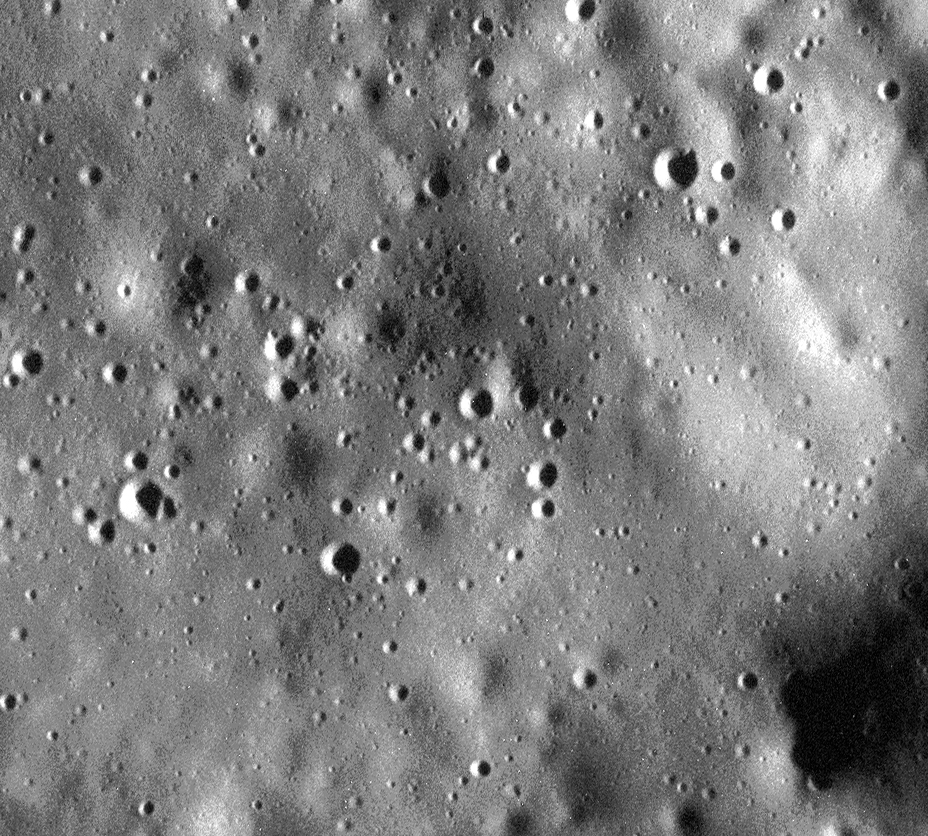

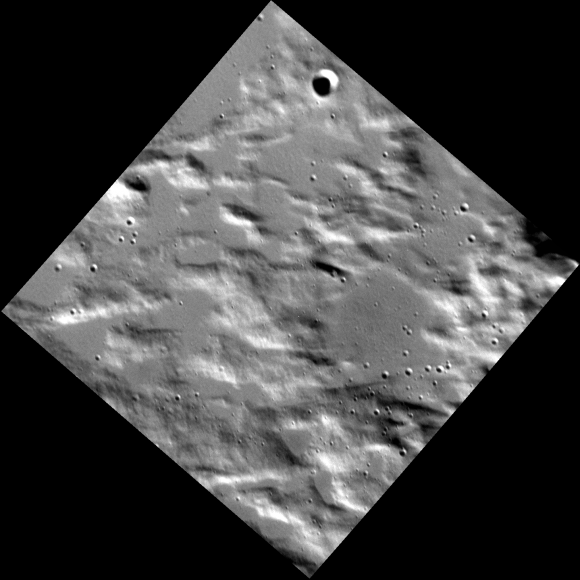

The first OCM burn was performed on June 17, raising MESSENGER’s orbit from 115 kilometers (71.4 miles) to 156.4 kilometers (97.2 miles) above the surface of Mercury. That was the ninth OCM of the MESSENGER mission, and at 11:54 a.m. EDT on Sept. 12, 2014, the tenth was performed.

Read more: Mercury’s Ready for Its Close-up, Mr. MESSENGER

According to the mission news article:

At the time of this most recent maneuver, MESSENGER was in an orbit with a closest approach of 24.3 kilometers (15.1 miles) above the surface of Mercury. With a velocity change of 8.57 meters per second (19.17 miles per hour), the spacecraft’s four largest monopropellant thrusters (with a small contribution from four of the 12 smallest monopropellant thrusters) nudged the spacecraft to an orbit with a closest approach altitude of 94 kilometers (58.4 miles). This maneuver also increased the spacecraft’s speed relative to Mercury at the maximum distance from Mercury, adding about 3.2 minutes to the spacecraft’s eight-hour, two-minute orbit period.

OCM-10 lasted for 2 1/4 minutes and added 3.2 minutes to the spacecraft’s 8-hour, 2-minute-long orbit. (Source)

The next two burns will occur on October 24 and January 21.

After its two final successful burns MESSENGER will be out of propellant, making any further OCMs impossible. At the planned end of its mission MESSENGER will impact Mercury’s surface in March of 2015.

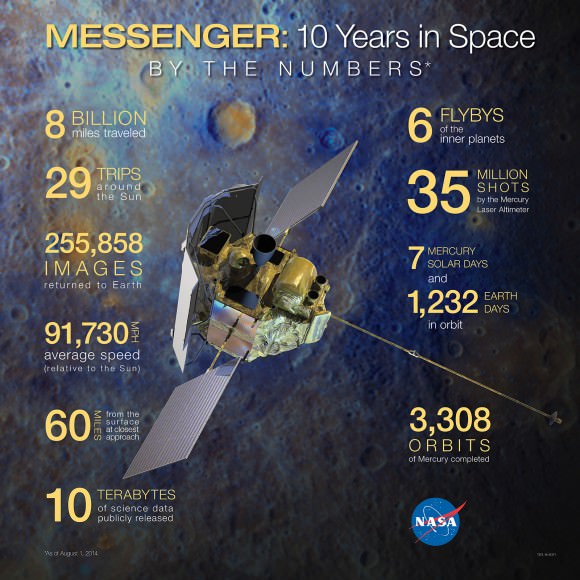

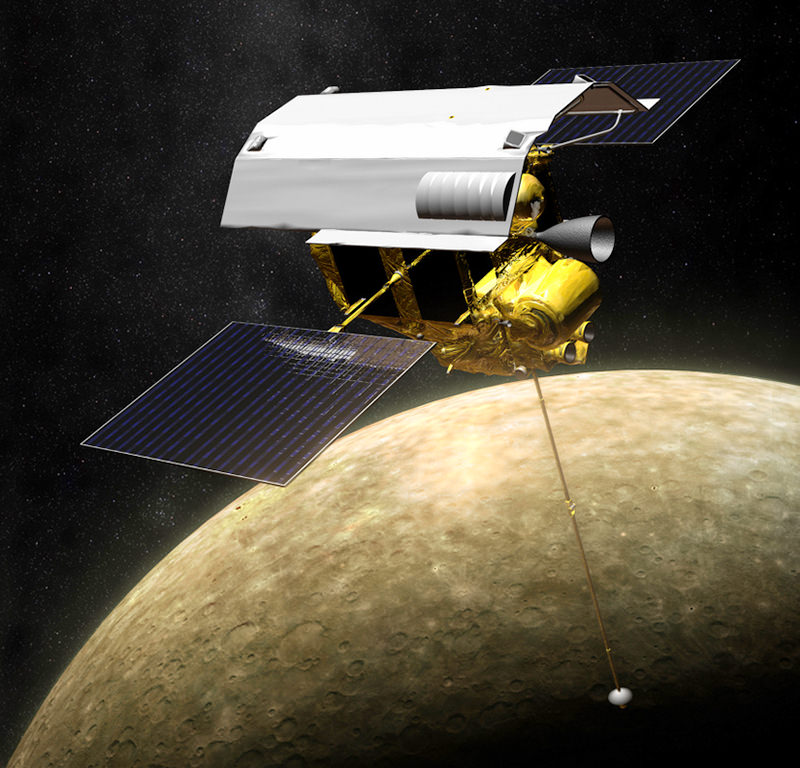

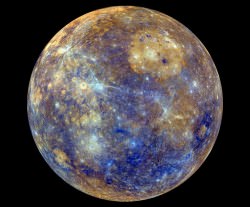

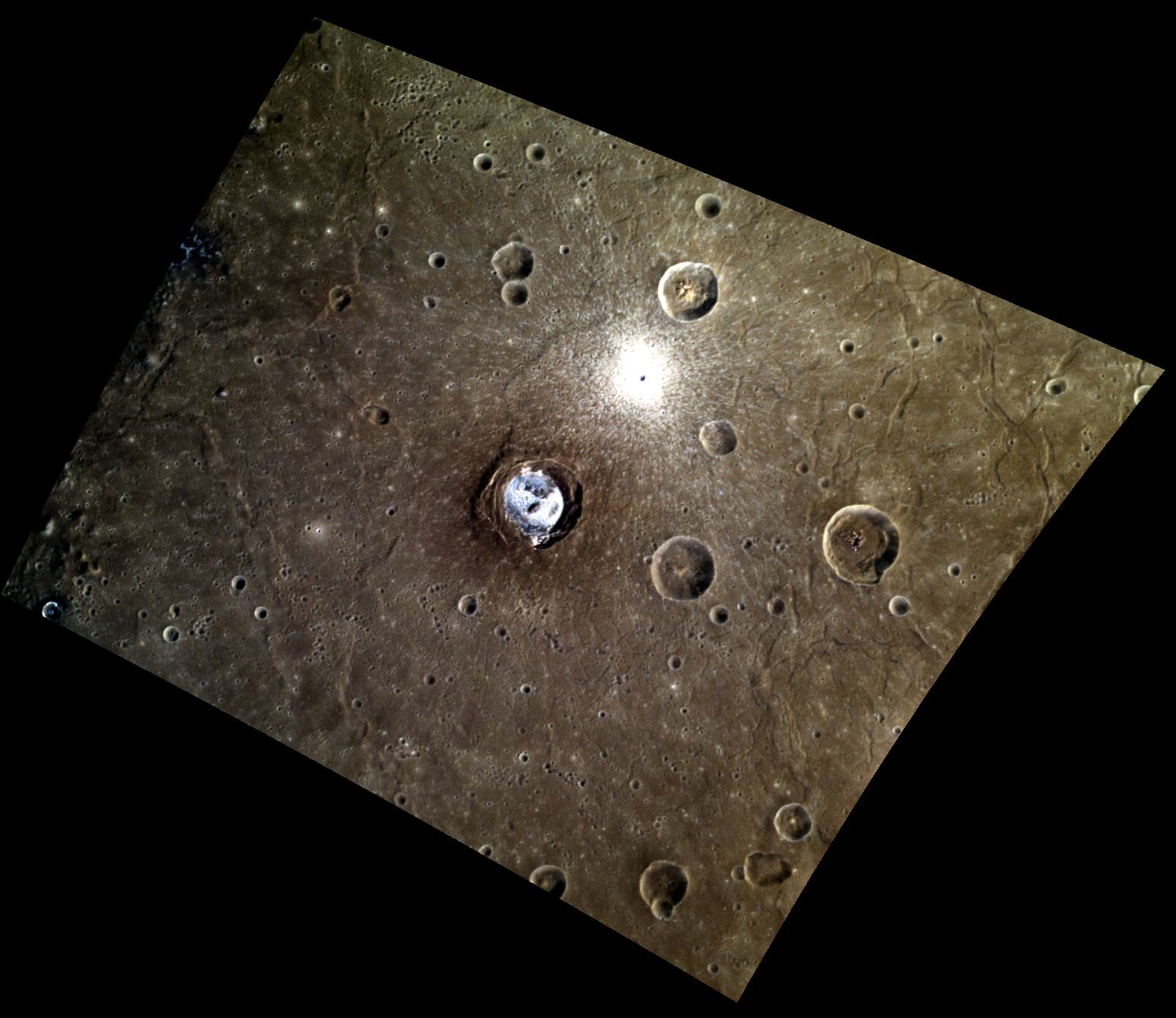

Built and operated by The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory (JHUAPL), MESSENGER launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on August 3, 2004. It entered orbit around Mercury on March 18, 2011, the first spacecraft ever to do so. Since then it has performed countless observations of our Solar System’s innermost planet and has successfully mapped 100% of its surface. Check out the infographic below showing some of the amazing numbers racked up by MESSENGER since its launch ten years ago, and read more about the MESSENGER mission here.