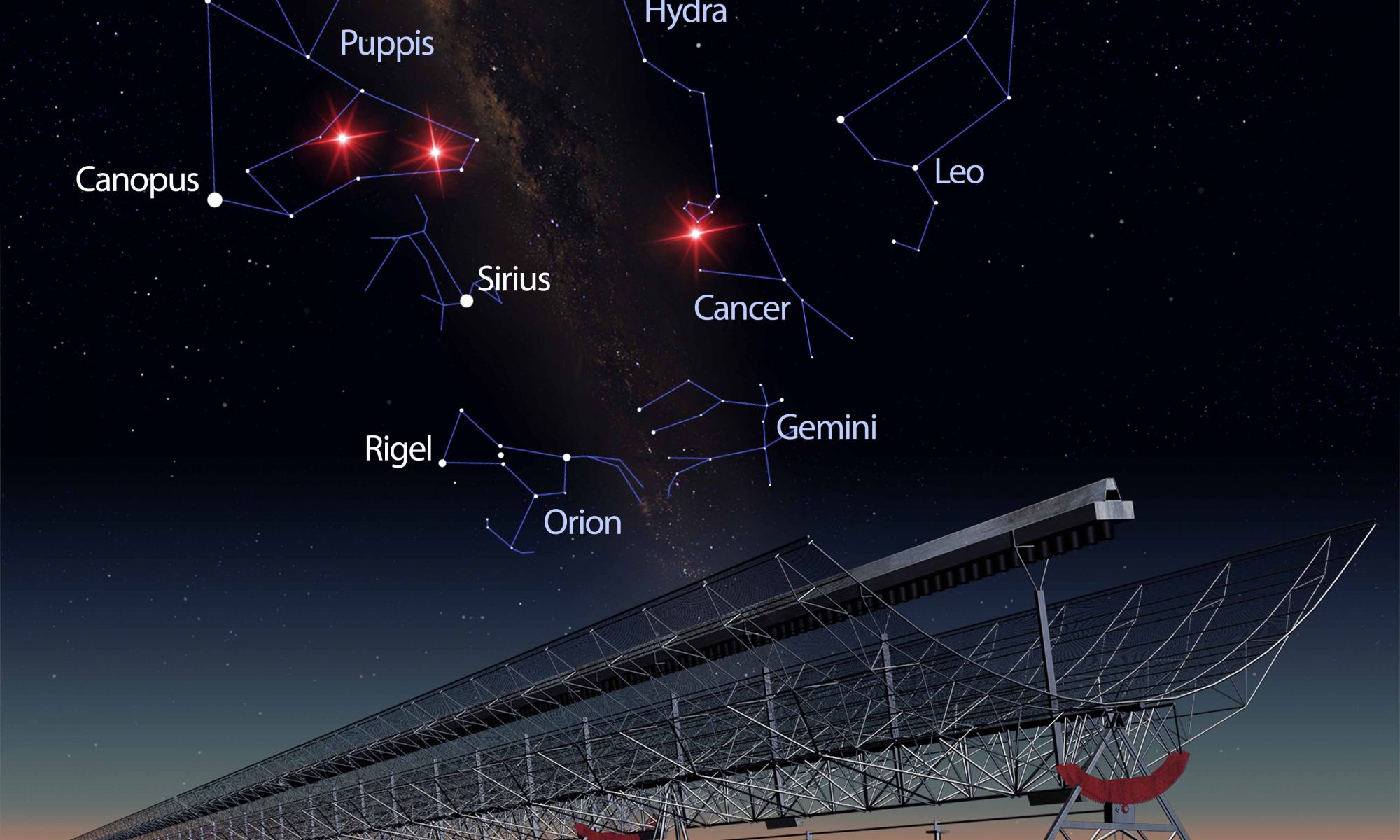

The Breakthrough Listen project has made several attempts to find evidence of alien civilizations through radio astronomy. Its latest effort focuses attention on the center of our galaxy.

Continue reading “Breakthrough Listen Searched for Signals From Intelligent Civilizations Near the Center of the Milky Way”One Type of Fast Radio Bursts… Solved?

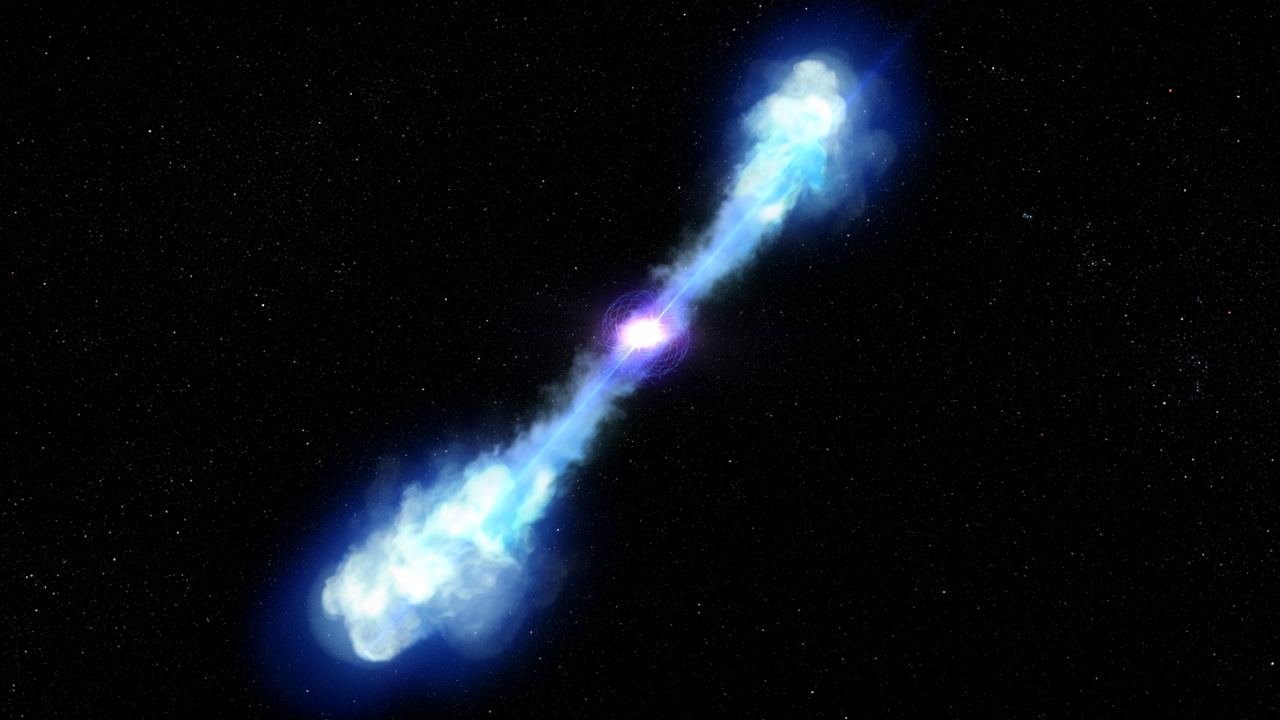

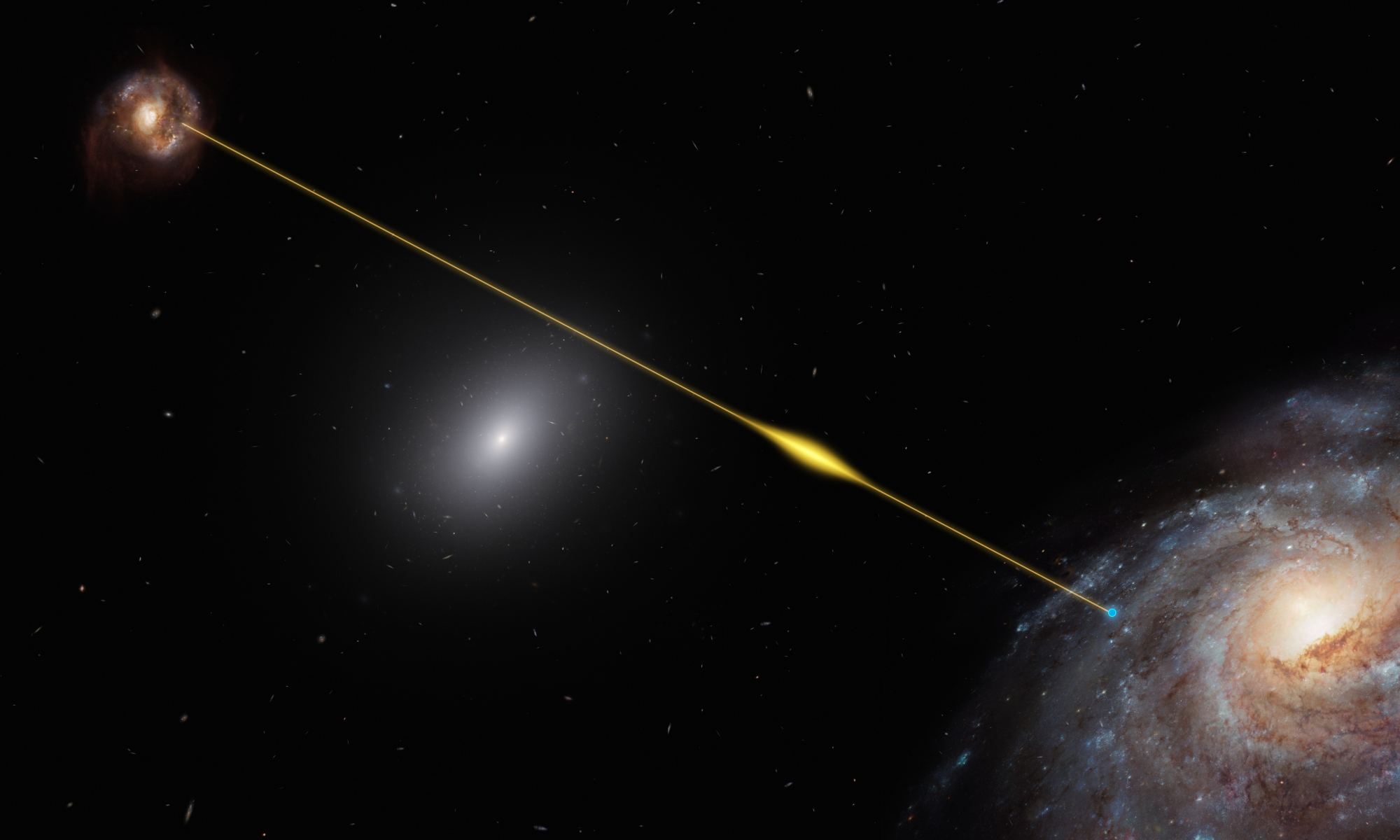

Every now and then there is a burst of radio light in the sky. It lasts for just milliseconds before fading. It’s known as a Fast Radio Burst (FRB), and they are difficult to observe and study. We know they are powerful bursts of energy, but we aren’t entirely sure what causes them.

Continue reading “One Type of Fast Radio Bursts… Solved?”Only 31 Magnetars Have Ever Been Discovered. This one is Extra Strange. It’s Also a Pulsar

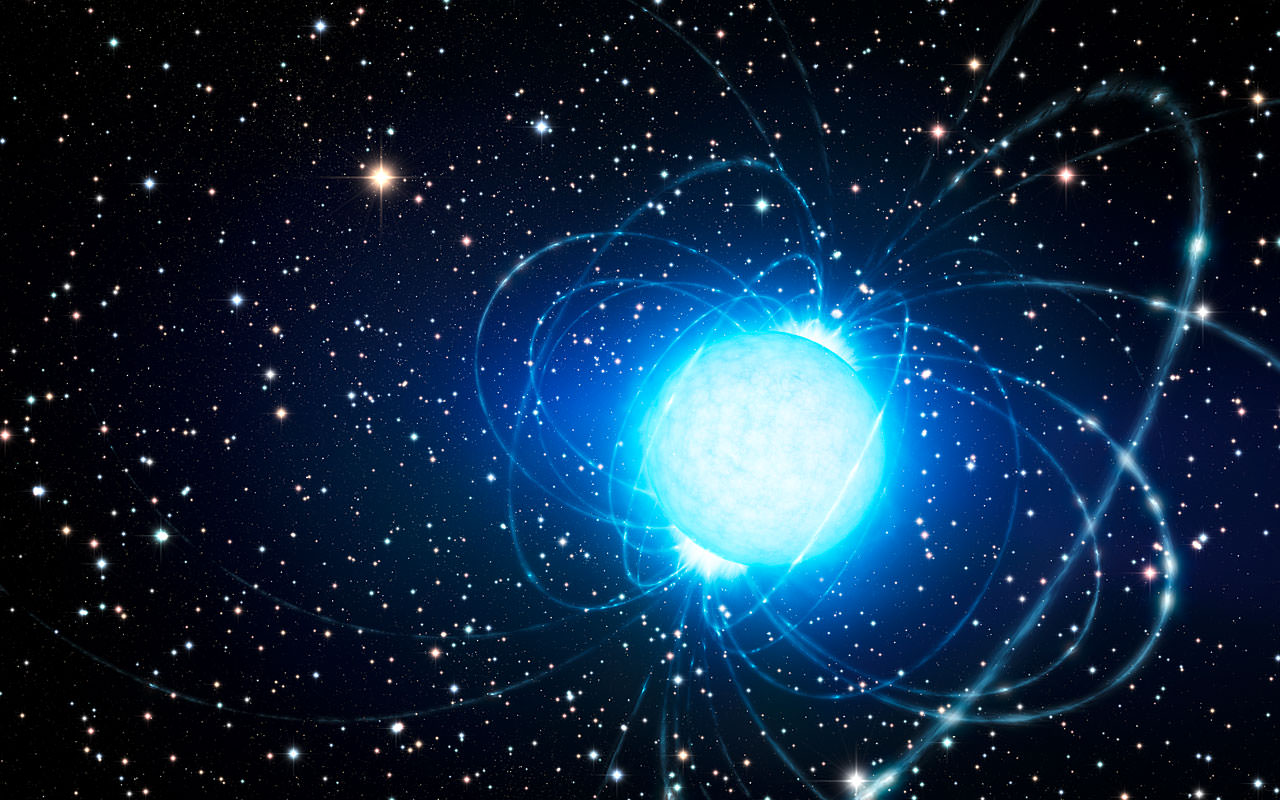

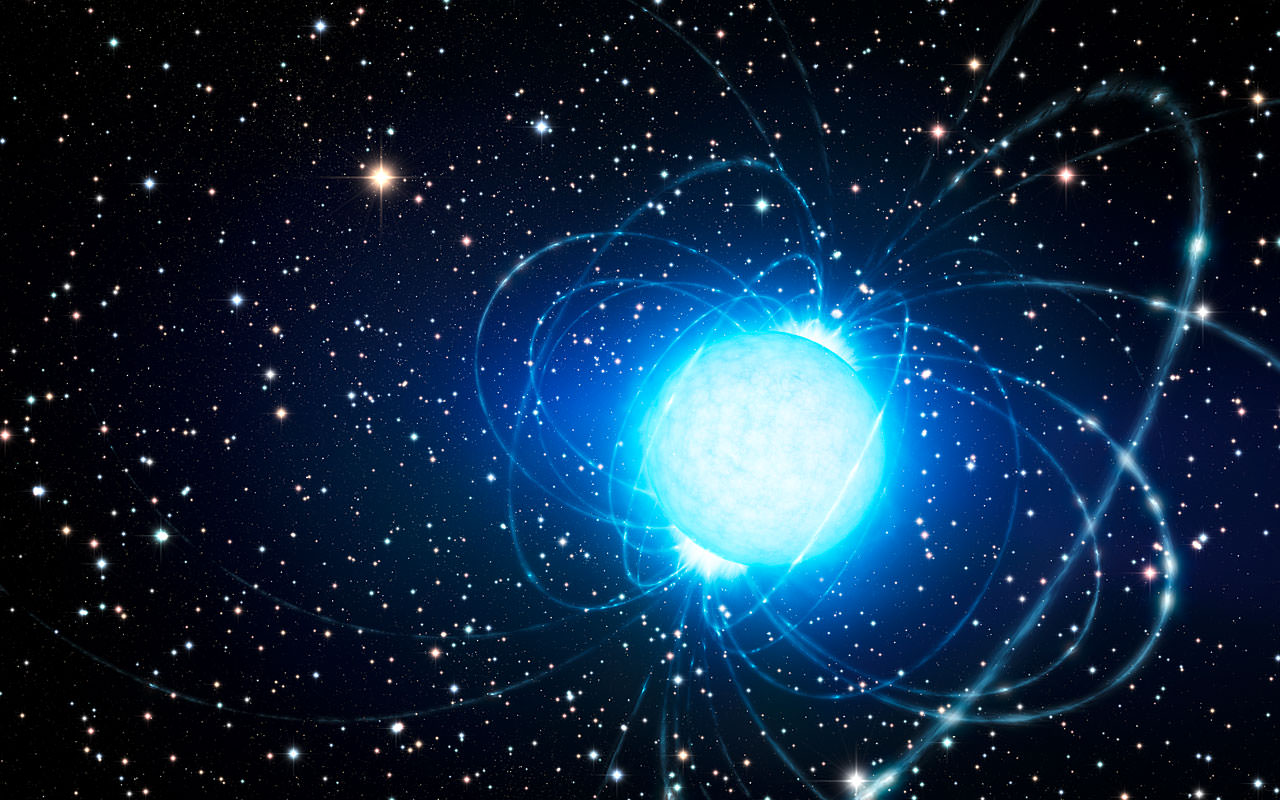

Some of the most stunningly powerful objects in the sky aren’t necessarily the prettiest to look at. But their secrets can allow humanity to glimpse some of the more intricate details of the universe that are exposed in their extreme environs. Any time we find one of these unique objects it’s a cause for celebration, and recently astronomers have found an extremely unique object that is both a magnetar and a pulsar, making it one of only 5 ever found.

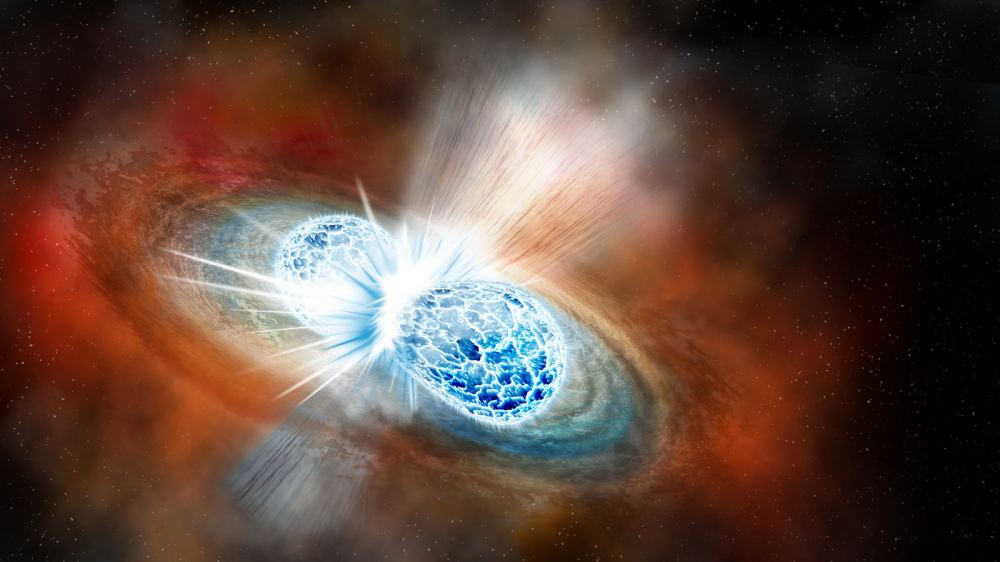

Continue reading “Only 31 Magnetars Have Ever Been Discovered. This one is Extra Strange. It’s Also a Pulsar”Astronomers think they’ve seen a magnetar form for the first time; the collision of two neutron stars

A magnetar is a neutron star with a magnetic field thousands of times more powerful than those of typical neutron stars. Their fields are so strong that they can generate powerful, short-duration events such as soft gamma repeaters and fast radio bursts. While we have learned quite a bit about magnetars in recent years, we still don’t understand how neutron stars can form such intense magnetic fields. But that could soon change thanks to a new study.

Continue reading “Astronomers think they’ve seen a magnetar form for the first time; the collision of two neutron stars”Fast radio bursts within the Milky Way seem to be coming from magnetars

Fast radio bursts are some of the most mysterious events known in astronomy, but they are slowly becoming better understood. Case in point: recent observations of a fast radio burst in the Milky Way reveals the powerhouse behind the blasts: a flaring magnetar.

Continue reading “Fast radio bursts within the Milky Way seem to be coming from magnetars”New Simulation Shows Exactly What’s Happening as Neutron Stars Merge

Neutron stars are the remnants of massive stars that explode as supernovae at the end of their fusion lives. They’re super-dense cores where all of the protons and electrons are crushed into neutrons by the overpowering gravity of the dead star. They’re the smallest and densest stellar objects, except for black holes, and possibly other arcane, hypothetical objects like quark stars.

When two neutron stars merge, we can detect the resulting gravitational waves. But some aspects of these mergers are poorly-understood. One question surrounds short-lived gamma-ray bursts from these mergers. Previous studies have shown that these bursts may come from the decay of heavy elements produced in a neutron star merger.

A new study strengthens our understanding of these complex mergers and introduces a model that explains the gamma rays.

Continue reading “New Simulation Shows Exactly What’s Happening as Neutron Stars Merge”A Repeating Fast Radio Burst Has Been Found. It Flares for 4 Days and then Remains Silent for 12 Days

Five hundred million light-years from Earth, there is a deeply unusual object. It is radio silent for 12 days, then erupts in bright radio bursts. These fast radio bursts occur randomly over four days, then the object goes silent for another 12 days. Astronomers have observed this object for 500 days, and the pattern always repeats, like clockwork. We still aren’t sure what the object is.

Continue reading “A Repeating Fast Radio Burst Has Been Found. It Flares for 4 Days and then Remains Silent for 12 Days”A Fast Radio Burst Has Been Detected From Inside The Milky Way

Now and then there are bright flashes of radio light in the sky, and they are bothering astronomers. They are called Fast Radio Bursts (FRBs), and they’re like the chirp of a smoke alarm that needs its battery changed. They last for such a short time that it’s difficult to track down the source. They have become a nagging mystery in astronomy.

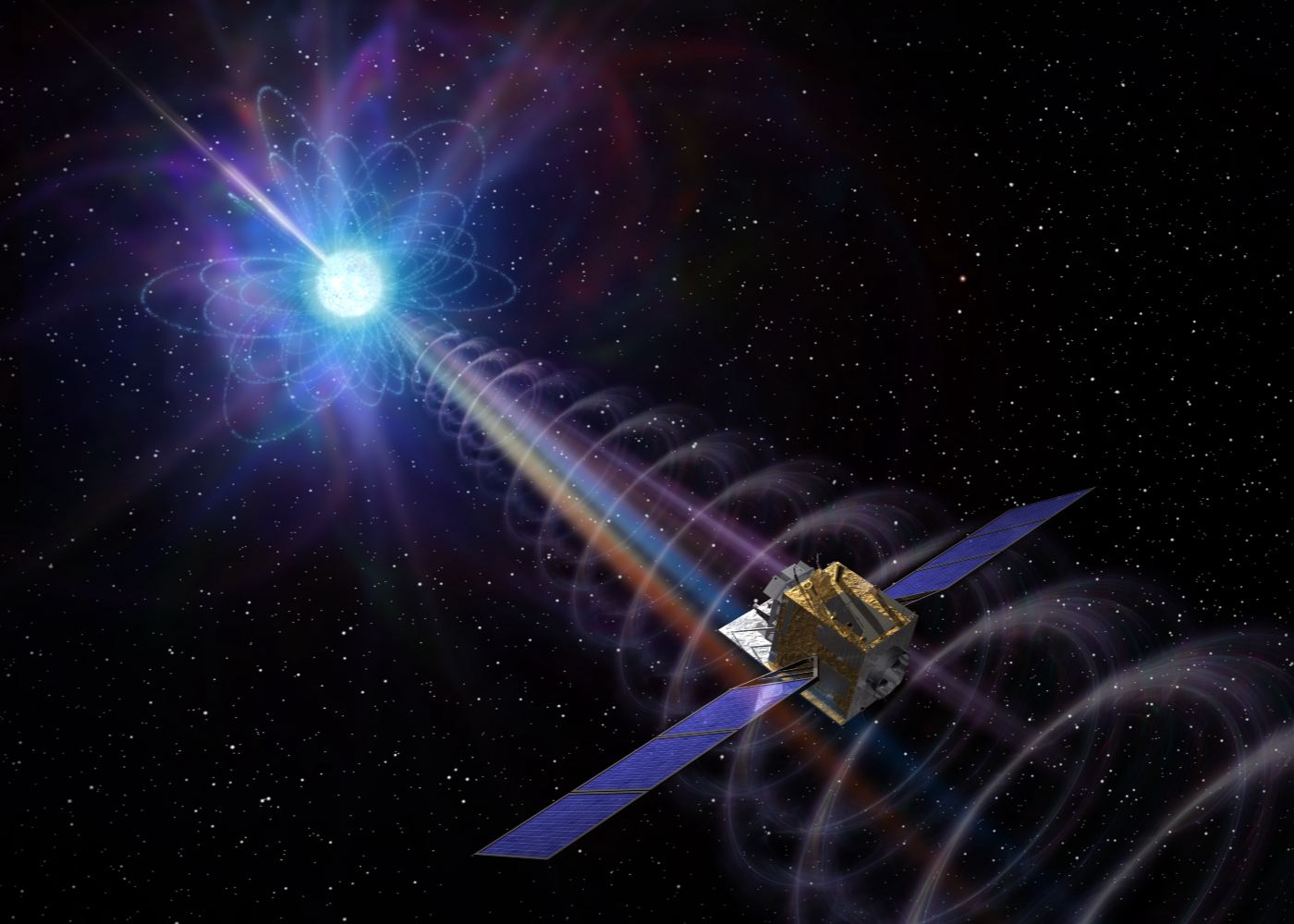

Continue reading “A Fast Radio Burst Has Been Detected From Inside The Milky Way”Astronomers are Using NASA’s Deep Space Network to Hunt for Magnetars

Right, magnetars. Perhaps one of the most ferocious beasts to inhabit the cosmos. Loud, unruly, and temperamental, they blast their host galaxies with wave after wave of electromagnetic radiation, running the gamut from soft radio waves to hard X-rays. They are rare and poorly understood.

Some of these magnetars spit out a lot of radio waves, and frequently. The perfect way to observe them would be to have a network of high-quality radio dishes across the world, all continuously observing to capture every bleep and bloop. Some sort of network of deep-space dishes.

Like NASA’s Deep Space Network.

Continue reading “Astronomers are Using NASA’s Deep Space Network to Hunt for Magnetars”“With a Little Help From Their Friends,” Magnetars Form in Binary Systems, New Study Suggests

Astronomy is a discipline of extremes. We’re constantly searching for the most powerful, the most explosive, and the most energetic objects in the Universe. Magnetars — extremely dense and highly magnetic neutron stars — are no exception to the rule. They’re the strongest known magnets in the Universe, millions of times more powerful than the strongest magnets on Earth.

But their origin has eluded astronomers for 35 years. Now, an international team of astronomers think they’ve found the partner star of a magnetar for the first time, an observation that suggests magnetars form in binary star systems.

When the core of a massive star runs out of energy, it collapses to form an incredibly dense neutron star or black hole. Meanwhile the outer layers of the star blow away in a stupendously powerful explosion, known as a supernova. A teaspoon of “neutron star stuff” would have a mass of about a billion tonnes, and a few cups would outweigh Mount Everest.

Magnetars are an unusual form of neutron stars with powerful magnetic fields. While there are roughly a dozen known magnetars in the Milky Way, one stands out as being the most peculiar. CXOU J164710.2-455216 — located 16,000 light-years away in the young star cluster Westerlund 1 — is unlike any other magnetar because astronomers can’t see how it formed in the first place.

Astronomers estimate that this magnetar must have been born in the explosive death of a star about 40 times the mass of the Sun. “But this presents its own problem, since stars this massive are expected to collapse to form black holes after their deaths, not neutron stars,” said Simon Clark, lead author on the paper, in a press release. “We did not understand how it could have become a magnetar.”

So astronomers went back to the drawing board. The most promising solution suggested that the magnetar formed through the interactions of two massive stars orbiting one another. Once the more massive star began to run out of fuel, it transferred mass to the less massive companion, causing it to rotate more and more rapidly — a crucial ingredient to creating ultra-strong magnetic fields.

In turn, the companion star became so massive that it shed a large amount of its recently gained mass. This caused it “to shrink to low enough levels that a magnetar was born instead of a black hole — a game of stellar pass-the-parcel with cosmic consequences” said coauthor Francisco Najarro from the Centro de Astrobiología in Spain.

There was only one slight problem: no companion star had been found. So Clark and colleagues set out to search for a star in other parts of the cluster. They used ESO’s Very Large Telescope to hunt for a hypervelocity star — an object escaping the cluster at an incredible speed — that might have been kicked out of orbit by the supernova explosion that formed the magnetar.

One star, known as Westerlund 1-5, matched their prediction.

“Not only does this star have the high velocity expected if it is recoiling from a supernova explosion, but the combination of its low mass, high luminosity and carbon-rich composition appear impossible to replicate in a single star — a smoking gun that shows it must have originally formed with a binary companion,” said coauthor Ben Ritchie from Open University.

The discovery suggests that double star systems may be essential for forming these enigmatic stars.

The paper has been published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, and is available for download here.