Roughly 4.5 billion years ago, scientists theorize that Earth experienced a massive impact with a Mars-sized object (named Theia). In accordance with the Giant Impact Hypothesis, this collision placed a considerable amount of debris in orbit, which eventually coalesced to form the Moon. And while the Moon has remained Earth’s only natural satellite since then, astronomers believe that Earth occasionally shares its orbit with “mini-moons”.

These are essentially small and fast-moving asteroids that largely avoid detection, with only one having been observed to date. But according to a new study by an international team of scientists, the development of instruments like the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST) could allow for their detection and study. This, in turn, will present astronomers and asteroid miners with considerable opportunities.

The study which details their findings recently appeared in the Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences under the title “Earth’s Minimoons: Opportunities for Science and Technology“. The study was led by Robert Jedicke, a researcher from the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and included members from the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), the University of Washington, the Luleå University of Technology, the University of Helsinki, and the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos.

As a specialist in Solar System bodies, Jedicke has spent his career studying the orbit and size distributions of asteroid populations – including Main Belt and Near Earth Objects (NEOs), Centaurs, Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs), comets, and interstellar objects. For the sake of their study, Jedicke and his colleagues focused on objects known as temporarily-captured orbiters (TCO) – aka. mini-moons.

These are essentially small rocky bodies – thought to measure up to 1-2 meters (3.3 to 6.6 feet) in diameter – that are temporarily gravitationally bound to the Earth-Moon system. This population of objects also includes temporarily-captured flybys (TCFs), asteroids that fly by Earth and make at least one revolution of the planet before escaping orbit or entering our atmosphere.

As Dr. Jedicke explained in a recent Science Daily news release, these characteristics is what makes mini-moons particularly hard to observe:

“Mini-moons are small, moving across the sky much faster than most asteroid surveys can detect. Only one minimoon has ever been discovered orbiting Earth, the relatively large object designated 2006 RH120, of a few meters in diameter.”

This object, which measured a few meters in diameter, was discovered in 2006 by the Catalina Sky Survey (CSS), a NASA-funded project supported by the Near Earth Object Observation Program (NEOO) that is dedicated to discovering and tracking Near-Earth Asteroids (NEAs). Despite improvements over the past decade in ground-based telescopes and detectors, no other TCOs have been detected since.

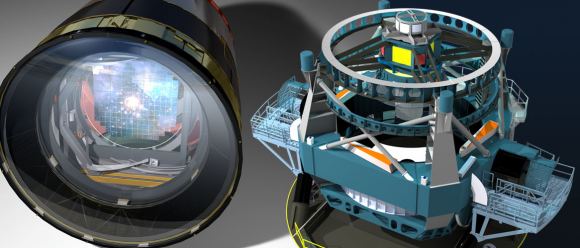

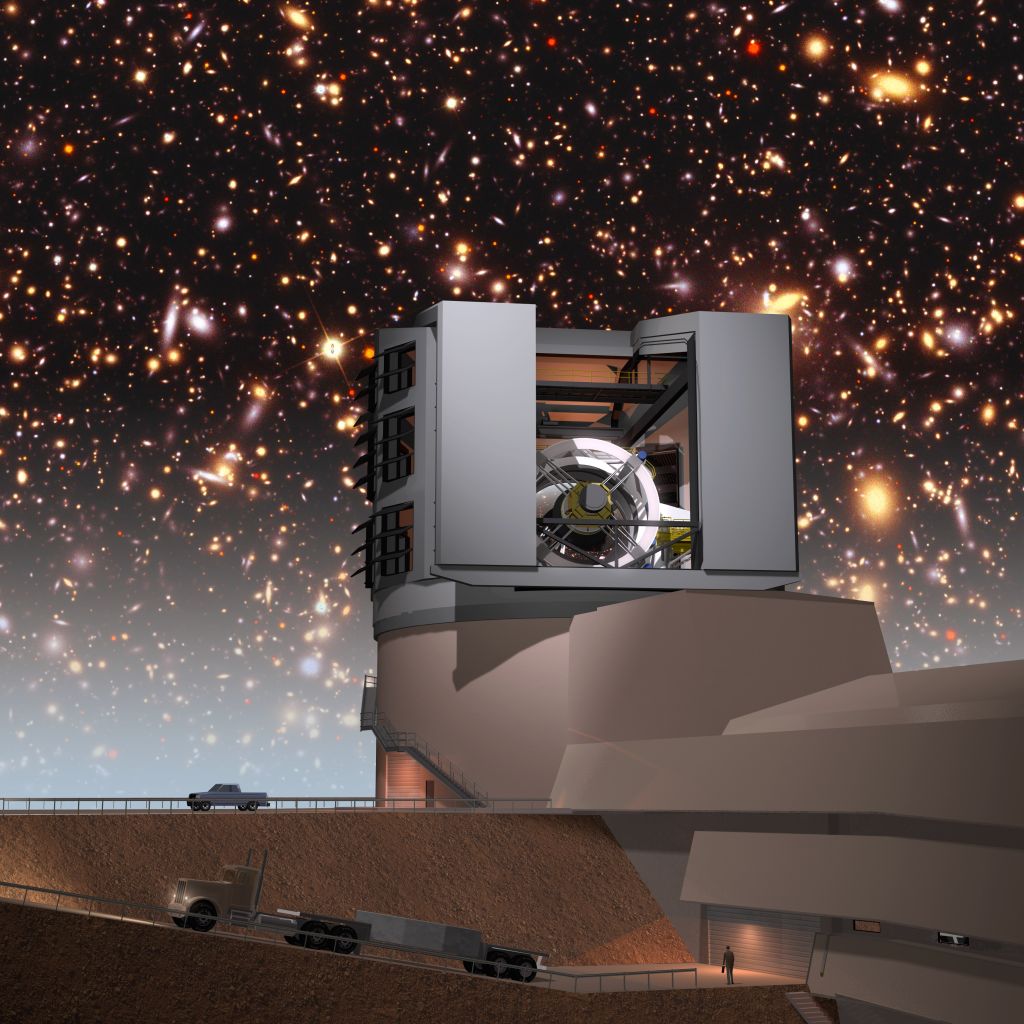

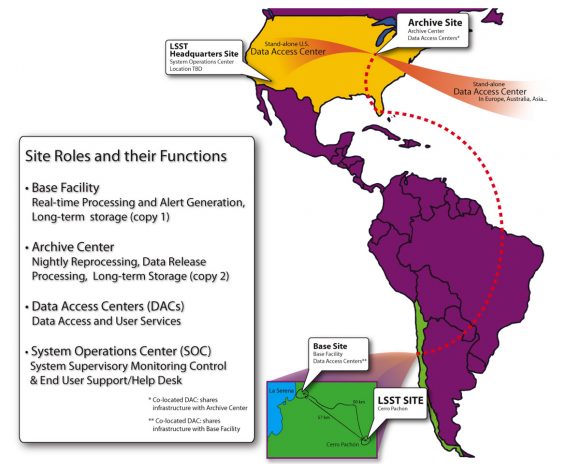

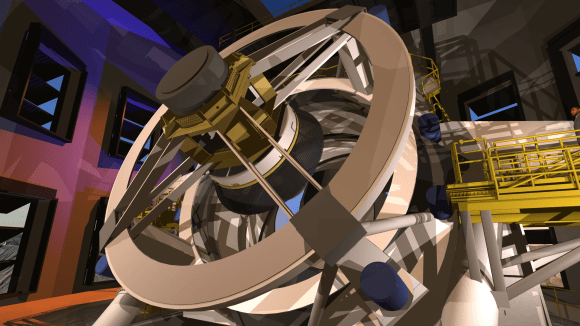

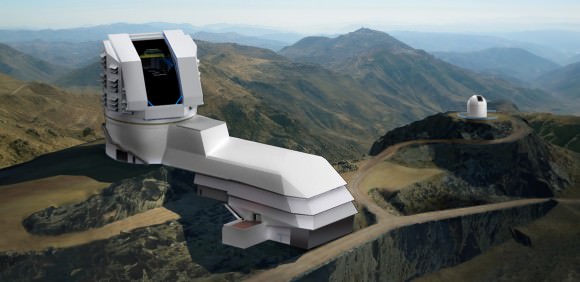

After reviewing the last ten years of mini-moon research, Jedicke and colleagues concluded that existing technology is only capable of detecting these small, fast moving objects by chance. This is likely to change, according to Jedicke and his colleagues, thanks to the advent of the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST), a wide-field telescope that is currently under construction in Chile.

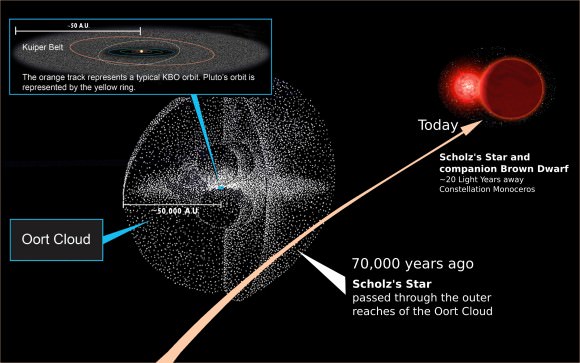

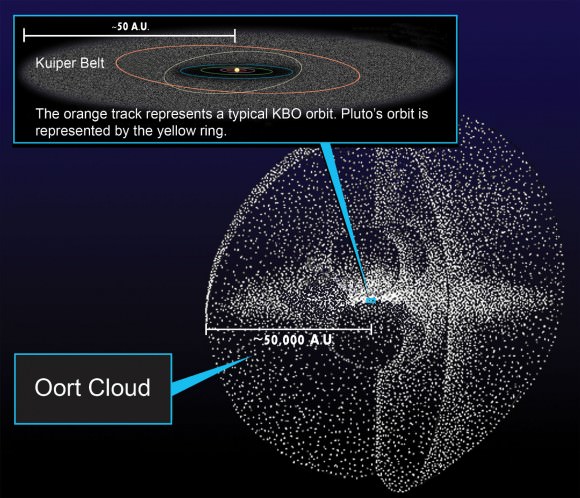

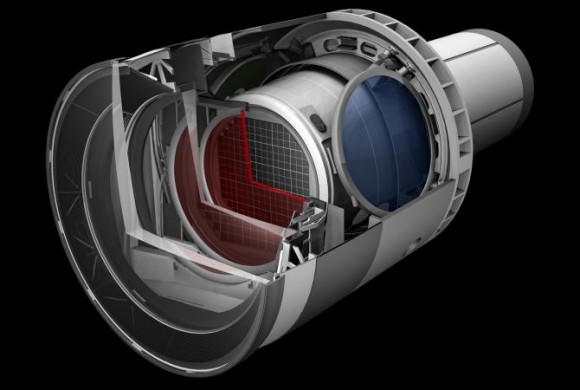

Once complete, the LSST will spend the ten years investigating the mysteries of dark matter and dark energy, detecting transient events (e.g. novae, supernovae, gamma ray bursts, gravitational lensings, etc.), mapping the structure of the Milky Way, and mapping small objects in the Solar System. Using its advanced optics and data processing techniques, the LSST is expected to increase the number of cataloged NEAs and Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) by a factor of 10-100.

But as they indicate in their study, the LSST will also be able to verify the existence of TCOs and track their paths around our planet, which could result in exciting scientific and commercial opportunities. As Dr. Jedicke indicated:

“Mini-moons can provide interesting science and technology testbeds in near-Earth space. These asteroids are delivered towards Earth from the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter via gravitational interactions with the Sun and planets in our solar system. The challenge lies in finding these small objects, despite their close proximity.”

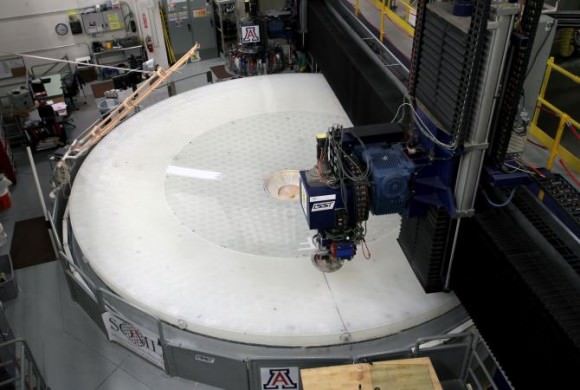

When it is completed in a few years, it is hoped that the LSST will confirm the existence of mini-moons and help track their orbits around Earth. This will be possible thanks to the telescope’s primary mirror (which measures 8.4 meters (27 feet) across) and its 3200 megapixel camera – which has a tremendous field of view. As Jedicke explained, the telescope will be able to cover the entire night sky more than once a week and collect light from faint objects.

With the ability to detect and track these small, fast objects, low-cost missions may be possible to mini-Moons, which would be a boon for researchers seeking to learn more about asteroids in our Solar System. As Dr Mikael Granvik – a researcher from the Luleå University of Technology, the University of Helsinki, and a co-author on the paper – indicated:

“At present we don’t fully understand what asteroids are made of. Missions typically return only tiny amounts of material to Earth. Meteorites provide an indirect way of analyzing asteroids, but Earth’s atmosphere destroys weak materials when they pass through. Mini-moons are perfect targets for bringing back significant chunks of asteroid material, shielded by a spacecraft, which could then be studied in detail back on Earth.”

As Jedicke points out, the ability to conduct low-cost missions to objects that share Earth’s orbit will also be of interest to the burgeoning asteroid mining industry. Beyond that, they also offer the possibility of increasing humanity’s presence in space.

“Once we start finding mini-moons at a greater rate they will be perfect targets for satellite missions,” he said. “We can launch short and therefore cheaper missions, using them as testbeds for larger space missions and providing an opportunity for the fledgling asteroid mining industry to test their technology… I hope that humans will someday venture into the solar system to explore the planets, asteroids and comets — and I see mini-moons as the first stepping stones on that voyage.”

Further Reading: Science Daily, Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences